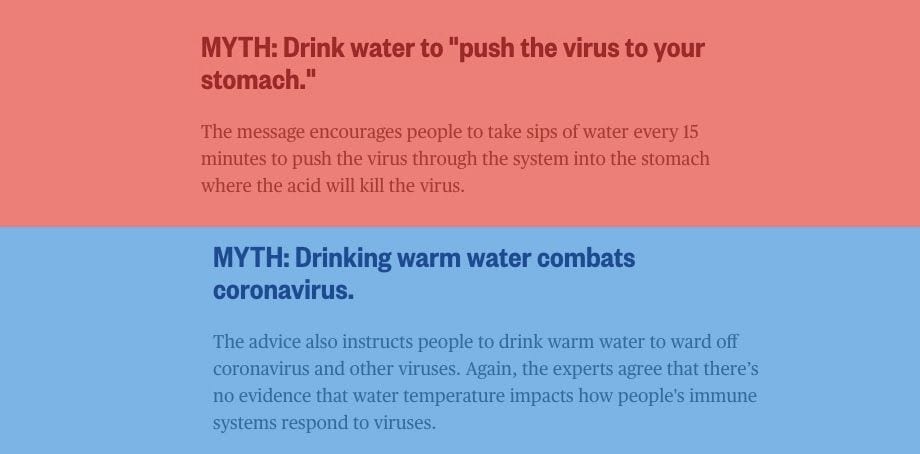

Some Visual Thoughts On Immunity & Water

by: Gal Leshem , October 12, 2020

by: Gal Leshem , October 12, 2020

Spending so much time scrubbing my hands in the bathroom sink over these last few months got me thinking about water. In the beginning, we were constantly being told to wash our hands. Now it has become a habit. From the early days of the spread of the virus, when the information was (and still is) unclear, the one solid piece of advice, the one undoubted guideline that we were given, was to wash our hands. Repeatedly. For some time now, it has seemed as though water has been our only form of protection from the invisible enemy that has entered our lives. As we fear that our immune system will disappoint us in protecting our bodies from invasion, we resort to washing our hands.

In ‘The Biopolitics of Postmodern Bodies: Constitutions of Self in Immune System Discourse’, Donna Haraway discusses our perceptions of the body’s immunity through the scientific-cultural imagination of the immune system. The immune system, an elusive mechanism, is responsible for the recognition and differentiation between the self and the Other. The scientific discourse of our time suggests that once such differentiation is achieved, the immune system can attack the invader, the foreign body that infiltrates the supposedly cohesive and united self. If immunity is seen as the warding off of a possible intruder, that which comes from outside and has no room inside, what can water tell us about the ways we seek to guard ourselves against a possible invasion.

Taking on Haraway’s view that ‘the immune system is both an iconic mythic object in high-technology culture and a subject of research and clinical practice of the first importance’, I will take a closer look at the mythic aspects of water as immunity. I will trace a visual genealogy that links the two—water, protection—through myth, legend and folklore. In Haraway’s words, ‘Myth, laboratory, and clinic are intimately interwoven’ (1991: 205). The natural world has always served as a fertile ground for beliefs and legends aimed at producing mechanisms of control and protection from the unknown and the menacing. In different cultures, trees were believed to be the dwellings of demons or saints. Some plants received amulet status, and were used to protect against wicked spirits, the evil eye, misfortune, and other hazards. Some sites have been given the status of sacred places because a certain tree grows in the area. In this article, I wish to propose a visual reading of water as another natural element connected to notions of immunity. As with immunity itself, water functions as both metaphor, myth and a scientific ‘truth’ of protection. Recounting her first encounter with the original myth of immunity, the Greek story of Achilles, Eula Biss claims that ‘immunity is a myth, these stories suggest, and no mortal can ever be made invulnerable’ (2014: 1). Immunity is a myth as nobody can be protected from harm, because our bodies are fragile and mortal, because they are bound to be hurt. But immunity is also a myth in the sense that it is what myths are made of. Our deep understanding that we have no control over the full protection of our bodies, and the intrinsic fear this knowledge generates, feeds our desire for beliefs and superstition in seeking protection. Our primal need to feel protected has generated these stories for us to hold on to; to imagine our bodies invincible, to believe in what would make them so.

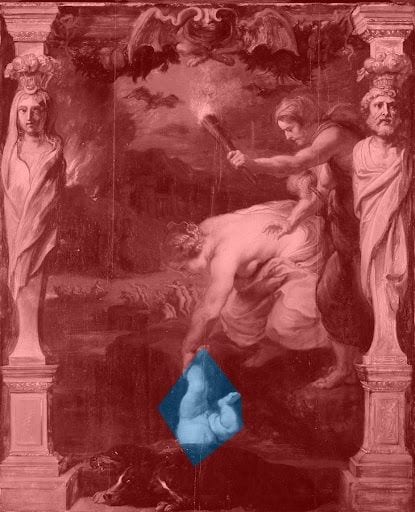

Famously, in Greek mythology, baby Achilles is dipped into the magical waters of the river Styx by his mother, leaving his whole body but his heel shielded from danger. What can the story of Achilles teach us about water? Why does the first myth of immunity begin at the river? What sort of protective shield does a river provide within our cultural imagination? Perhaps it was not the powerful forces of the Styx that gave Achilles his defence, turning his skin into a shield nothing could penetrate; perhaps this story is about water itself, and its imagined ability to wash off possible harms.

And what of the biblical story of the flood? Another water story. God punishes humanity for its crimes, and rains a flood upon the earth. The myth of the flood is not told as a tragedy, but as a fresh beginning for the world. The protagonist of the story through whom the myth is conveyed is Noah, who builds the ark and gains protection. We are used to thinking about the ark itself as the guard and refuge from natural or godly disaster. The ark is the proposed shelter: a vessel made of strong wood, large enough to contain all those who need to survive the flood and repopulate the world.

But what if it was not the ark that provided immunity, but the flood itself, the water itself? In the story, water is what serves to protect humanity from the pollution of immorality. The water washed away the wicked, cleared the land of those who did not deserve it, leaving it shiny and pure. The word cleansing comes to mind. Only the standard of men, that which deserves to replicate, to reproduce itself, shall populate the earth.

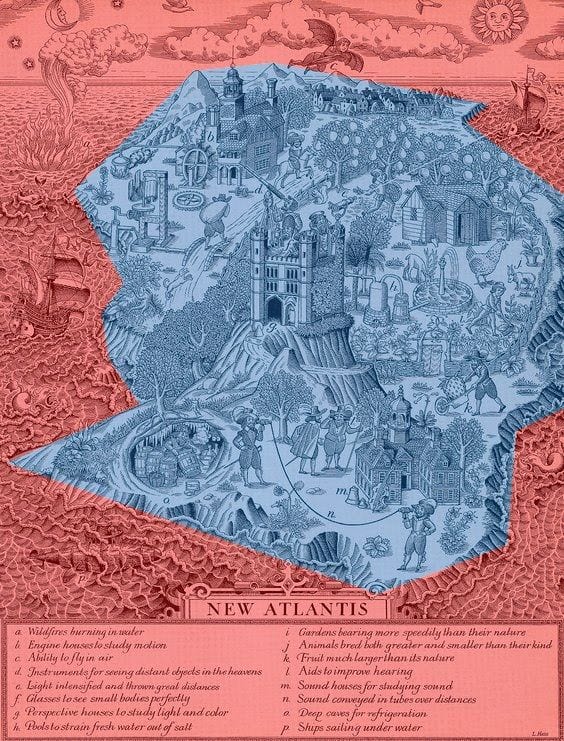

But water not only washes away the wicked. By forming a barrier to keep invaders out, it also encapsulates the unit that must be protected. Another myth tells us how water might ‘protect’ a social body by encasing it as within a unified skin, creating one homogeneous body. In the myth of Atlantis, a whole nation is submerged in water. This myth of a legendary society of a godlike race was, not surprisingly, taken up by Nazi Germany to serve its own ideological purposes. Francis Bacon’s utopia The New Atlantis is a society based on western scientific practices. It is an ideal that comes into being:

You shall understand that there is not under the heavens so chaste a nation as this of Bensalem; nor so free from all pollution or foulness (Bacon 1626).

A pure society, one social body, maintaining its unity as it submerges in water.

Jumping forward in time to present-day London. In 2018, the US embassy put up the first moat built in the UK since the 19th century. Constructed as part of advanced defence architecture, this medieval mechanism was created as a counter-terrorism apparatus, to aid in the prevention of threats to, and attacks on, the building. The moat is a simple and technical defence mechanism: a deep canal, a water basin, a lake. Those who come with vehicles from one side will not be able to cross to the other side of the water. Architecturally (or geographically) speaking, the moat isolates the structure in its centre, separating it from the surrounding area. In the US Embassy building, a high tech anti-terrorist architectural defence includes ‘triple-glazed and blast-proof glass walls, raised terraces and sunken trenches instead of a wire fence, and a Faraday cage—a mesh of conductive material to prevent electronic eavesdropping’ as well as a ‘[d]eep moat designed to stop a truck (Morrison 2017).

But what kind of security does the moat provide? In the context of these technologies, can the water of the moat be seen solely as a practical device against possible attack? The water feature surrounding the building serves more as a declaration of intention, an archaic example of psychological warfare. It only takes a bit of water to differentiate land from land, a simple way of marking and maintaining an inside and an outside, a self and an Other.

Immunity at its best. Water provides the feeling of separation that we seek in order to feel safe. Like Achilles, like the flood, the design harnesses the myth of immunity and water as that which keeps the bad guys out. In her essay ‘Effective Economies’, Sarah Ahmed discusses the ways in which certain bodies are formed to be seen as dangerous through a rhetoric of invasion and protection. If in Haraway the distinction between self and other takes place in the internal universe of the cellular, Ahmed’s discussion is performed on the epidermis level of the skin. The social body, in this case, the nation, is united through the marking of certain bodies as invaders. She, too, uses the word floods , this time in its oppositional form: ‘fear speaks the language of “floods” and “swamps,” of being invaded by inappropriate others, against whom the nation must defend itself’ (2004: 132). Though the flood does not here protect against the unwanted, it still sticks together a language of water and defence. Against the ‘flood of invaders,’ the nation must unite and immune itself.

In Learning from the Virus, Paul B. Preciado suggests that during the current pandemic, the management of individual bodies mirrors the border politics we have seen in Europe and elsewhere in recent years. The mechanisms that kept migrants outside of the homogenised community of the nation-state—in the enclosure of bodies that crossed the Mediterranean Sea—are now being applied to the bodies of citizens in those countries. Preciado writes:

Lesbos now starts at your doorstep. Calais blows up in your face. The new frontier is the mask. The air that you breathe has to be yours alone. The new frontier is your epidermis. The new Lampedusa is your skin (Preciado 2020).

In The Construction of Postmodern Bodies, Haraway’s conclusion is that the myth of the immune system is falsely constructed: she claims that the Self and the Other are already implicated within the body in an endless process of mirroring and replication; that the cohesive individual never existed in the first place. Perhaps the myths of water need to change as well. Instead of symbolising immunisation and defence, barriers of inside and outside, we can use them to make new myths, ones that call for spills and mixing, for leaky identities and contaminated selves.

Astrida Neimanis’ Hydrofeminism provides such a myth. By shifting the attention from the external use of water on the body to an internal one, she connects our watery bodies to other bodies of water around us. The leaking body, a gendered body at first, forms a new logic for (un)thinking the western politics of self and other. Avoiding the pitfalls of an essentialist reading of water as a solely feminine attribute of the biology of female bodies, Niemanis uses water as a strategy that dismantles the very boundaries of the conceived self. She writes:

In an ocular-centric culture, some of these membranes, like our human skin, give the illusion of impermeability. Still, we perspire, urinate, ingest, ejaculate, menstruate, lactate, breathe, cry. We take in the world, selectively, and send it flooding back out again (Neimanis 2012).

Through water, we can understand our connectivity to the world. The waters we drink are the same waters we pollute with the toxins of our neocolonial industries; the waters we urinate are washed back to the seas along with the chemicals our bodies consumed. The waters outside us are the same as the waters inside. The boundaries of our seemingly individually protected selves, sealed off in our skins, dissolve in this way of thinking. Attempting to locate ourselves as insulated from external harm is a problematic illusion at best. Our bodies are already implicated in the circulation of water and contamination. The differentiation between outside and inside loses its meaning, for better and for worse. The watery ethics that Hydrofeminism offers rely on this understanding of the liquidation of boundaries between self and other. Other bodies, other species, are part of the same stream and circulation in which we flow. The same stream we ingest. As a politics, water tells us to rethink our immunity as connected and interlaced with that of others. As a myth, it tells us just the same.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2004), ‘Affective Economies’, Social Text, 1 June 2004, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 117–139.

Bacon, Francis (1626), UK.

Biss, Eula (2014), On Immunity: An Inoculation, London: Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Haraway, Donna (1991), Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, New York: Routledge.

Morrison, Jonathan (2017), ‘US embassy: America Shows off its Thames Fortress’, The Times, 14 December 2017,

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/us-embassy-america-shows-off-its-thames-fortress-6n2kjmcv q (last accessed 26 June 2020).

Neimanis, Astrida (2012), ‘Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water’, in Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni & Fanny Söderbäck (eds), Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice , New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Preciado, Paul B. (2020), ‘Learning From The Virus’, Artforum May/June 2020, https://www.artforum.com/print/202005/paul-b-preciado-82823 (last accessed 26 June 2020)

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey