Images that (Do Not) Exist: Tina Modotti & Photographs from the Communist World

by: Paz Bustamante & Giulia Strippoli , June 25, 2022

by: Paz Bustamante & Giulia Strippoli , June 25, 2022

Dear Paz,

I am writing about the project I am working on, ‘Images that (do not) exist.’ I am inviting feminist photographers to produce images that connect gender and political struggle. This connection seems to me to be one of the more visible aspects of the extraordinary feminist struggle over the past years, and because of this, I am trying to explore the issue from various historical perspectives. One of these perspectives concerns the life and art of Tina Modotti. I am suggesting here that this distinction between art and life holds special meaning for her, as a photographer and a militant woman. Now I will tell you my idea and, if you find something in it that interests you, please send me some photographs.

The photographs that do not exist are the ones that Tina Modotti did not shoot, because she stopped taking photographs when she left Mexico to go to Berlin, and from there to the Soviet Union, from where she travelled a great deal as a militant part of the International Red Aid, before joining the struggle against Franco’s fascism in the Spanish Civil War. Tina Modotti was an antifascist militant woman at a time when there was an increase in and the consolidation of fascist ideologies and regimes. Opposition to the circulation of fascism was international and internationalist. The militants of the Antifascist Mexican League, where Tina Modotti was active, clearly expressed the concept by naming the Cuban dictator Machado the ‘Caribbean Mussolini,’ while Mussolini was identified as the ‘European Machado.’ In Mexico, Tina Modotti met and fell in love with Machado’s opponent, Juan António Mella, founder of the Cuban Communist Party, who had been imprisoned in La Habana, and was persecuted before emigrating to Mexico. He died as a result of an attempt made on his life while he was walking along a street at night with Tina.

Fascism influenced all Tina Modotti’s political activities: her revolt against the oppressive system established in her native land, her displacements, and peregrinations. Between 1925 and 1926, the Fascist Government annihilated and then forbade political parties, associations, and organisations whose actions were considered to be against the regime. Already ‘emigrated’ and ‘exiled,’ as an antifascist, Tina Modotti became subject of political persecution. Up until this point, I have described Tina as a militant, an antifascist, an emigrant, but I have not clearly said that she was a communist. I hesitate to write this, as I have to add that her communism was Stalinist communism, that she lived in the Soviet Union, that she was in a relationship with Vittorio Vidali, a communist accused of the murder of a number of anarchists and non-Stalinist republicans in the context of the Spanish civil war. And I must add that once installed in Moscow she stopped taking photographs; at least, no one has ever seen the images she shot.

Tina was born in Udine to a poor family in the border zone of Northeast Italy and, at the end of the nineteenth century, she spent a period of time in Austria with her family—misery-related migrations are a recurrent theme throughout history. Her uncle was a photographer. She was employed as a textile worker and attended elementary school at the same time. In 1913, she joined her father, who had emigrated to San Francisco. Here again, she was employed as a textile worker, but at the same time she dedicated herself to acting. In 1918 she moved to Los Angeles with the artist Roubaix de l’Abrie Richey, ‘Robo,’ whom she married. In Los Angeles, Tina acted in movies, portraying the role of the ‘seductive foreign woman.’ In Los Angeles she also met Edward Weston, and modelled for him; soon afterwards, they started a relationship. Robo in the meantime had been invited to exhibit his works in Mexico by Ricardo Gómez Robelo, the director of the Beaux Artes Academy, and Tina had planned to accompany him. Robo went first but by the timeTina arrived, he had already died of smallpox. She remained in Mexico for some time, during which time she made her first contact with mural painters. Upon her return to the United States, she stopped acting and intensified her relationship with Weston, both personally and professionally. No longer his model, she had become an apprentice photographer.

In 1923, Tina and Edward Weston went to Mexico, where she lived until 1930, while Weston returned to the United States in 1926. I would summarise the Mexican years in the following way: Tina became a photographer and a political militant; her eyes and hands transformed the technique acquired with Weston into a reinterpretation of reality, that is to say a demonstration of social documentation and the struggle against social injustice. In Mexico, her way of living and photographing expressed—it seems to me—the same feeling, the same inability to accept a predetermined shape to the world. She got involved in politics, photographed, and lived in the same way that she described good photographs were made:

By good is meant that photography which accepts all the limitations inherent in photographic technique and takes advantage of the possibilities and characteristics the medium offers. By bad photography is mean that which is done, one may say, with a kind of inferiority complex, with no appreciation of what photography itself offers. (Modotti 1929: 196-198).

I have written and rewritten this phrase many times, I have read it in its original version, I have pronounced it aloud. I am trying to understand if this is the key to understanding why Tina stopped photographing. Because she could not accept the limits? Because she could not use all the potentialities and possibilities? In 1930, the political situation changed. Mexico broke off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, the Communist Party was banned, dissidents were persecuted, and Tina Modotti—accused of having taken part in the attempt made on the life of the new President, Pascual Ortiz Rubio—spent two weeks in prison. Once liberated, she was expelled from the country. Since she could not return to Italy—Mussolini’s political police would have arrested her—she spent six months in Berlin before heading to Moscow. Then from Moscow, she joined the International Brigades and was sent to Spain to fight against Franco. At the end of the civil war, she finally managed to return to Mexico, and lived there until her death in 1942, at the age of 46.

Her photography could not have existed without her conception of the political struggle. There was such strength in the connection that Tina—through her gaze—established between the representation of reality and a revolutionary idea, that it is impossible to understand why she stopped taking photographs just as she managed to get herself to the land of the Revolution, Communist Russia.

Or perhaps it is too easy to understand.

And understanding makes me angry with Vittorio Vidali, with Elena Stasova, her boss at International Red Aid, with the PCUS, with Stalin, with the Soviet system of power, with hierarchical communism, with the sophisticated machine of political persecution and ‘deletion’ of adversaries. I feel angry with the idea of ‘art at the service of the people,’ when the definition of art, people and service was decided by powerful, manipulative, and oppressive men. And I feel angry with Tina, because in Moscow she was a Stalinist, and mostly because she stopped taking photographs.

Tina’s voice from the Communist world is not expressed in her photographs, but in her mission for the Red Aid, her constant work as a translator of the foreign press, in her Communist autobiography. The autobiographies of communists are an extraordinary combination of representation of class consciousness and auto framing in the order of the communist cause. An order conceived as discursive fil rouge, and as a command, in the Bolshevik sense. Because of this, I am arguing that perhaps Tina existed in the Soviet Union as she had always done in her life and photography: she accepted the limits, and she explored the possibilities of her autobiography. But maybe the limits were too extensive, and the possibilities were on a horizon too far away from the historical role that Tina had assigned to photography. Or life had eaten art. She had expressed something similar some years before, in a letter written in 1925, where she admitted to Weston that she had put too much art in her life, and with all the energy she had to devote to living she had begun to find that there was little left over for art. And I believe that in order to live in the Soviet Union, and then to live through the Spanish Civil War—in which she worked as a nurse—as well as for living with Vidali, she needed a lot of energy; maybe too much, leaving nothing over for photography. Tina had been ethically and aesthetically brave, she had innovated ways of watching, and she had done it for the idea of the revolution. When she stopped photographing, she also stopped watching. She did not see the elements of oppression in the Bolshevik world, or the Stalinist purges, she did not realise that she had stopped photographing. With the halt in her photographing there lies, in my view, the importance of photography and of political struggle. If the act of photographing had been a synonym of social transformation, struggle, and revolution, the end to photographing is the end of the revolution. And Tina should have felt this. Accepting the possibilities and the limits. Because of this, there are no images by her from the communist world, unless I imagine the mental compositions that Tina created.

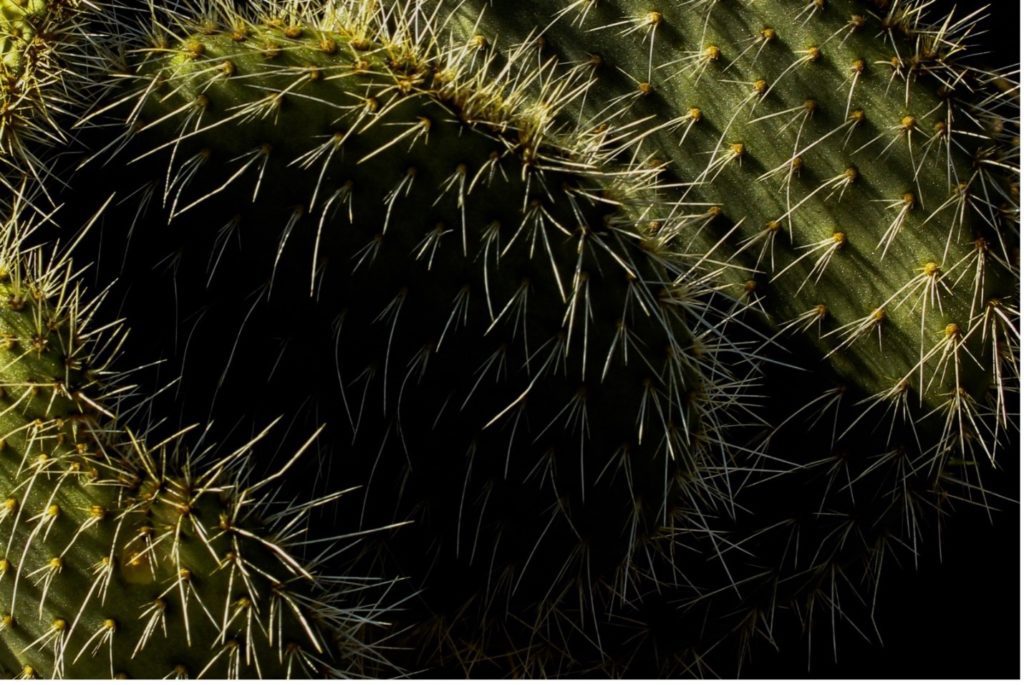

One of these is in Moscow, in the little office where Tina worked. Full of papers and smoke. The desk occupies the whole frame, her typewriter is represented in a similar position as that in the composition of ‘Mella’s Typewriter,’ but on the sheet the words ‘inspiration’ and ‘art,’ are missing. Indeed, there is no sheet in the paper bail, there is instead an issue of Pravda, already printed. And so, I think about a series of photographs from the Communist world, from Europe tarnished by Nazi Fascism and by the Spanish Civil War. They are similar to the almost 200 photographs that Tina took in Mexico. There are the portraits of women and men, the shapes of the city, the flowers, numerous details of bodies, the children, the symbols of struggle. The distance, the perspective, the composition, all are reminiscent of Tina’s photographs. But they lack the Mexican light. And the murals and their architectural particularities, the arches, the women from Tehuantepec, the Calla lilies, the cactuses, the roses—all are absent. Even wine glasses do not have the same texture in Moscow. The flag of anarcho-syndicalism is absent, the gazes of children and the hands are not there. Tina is not there. The hands that are doing the laundry are not the same, and the sombreros are absent, the sombreros that, thanks to the magic of her gaze and the photograph’s frame seemed to move rhythmically like a sea; the Machete is not there, and the hands of the puppeteer are caught up in too many wires.

After Mexico, Tina photographed extraordinarily little: the two nuns on a street in Berlin, a couple at the zoo, the beautiful portrait of a pregnant woman with two children, the pioneers—these images are not the product of my imagination, they exist, but the Mexican light is absent. Tina is still absent. Or at least the part of herself that lived in Mexico and believed in the revolution, to the point that for those who look at her photographs now, revolution seemed possible to achieve.

Here, Paz, is this brief story, hoping that it can inspire you to engage with the shape and the direction of photography, about photographic noise and silence. And about the need for, urgency in, and absence of images. About the presence and disappearance of photographs and bodies.

Thanks, Giulia.

Notes:

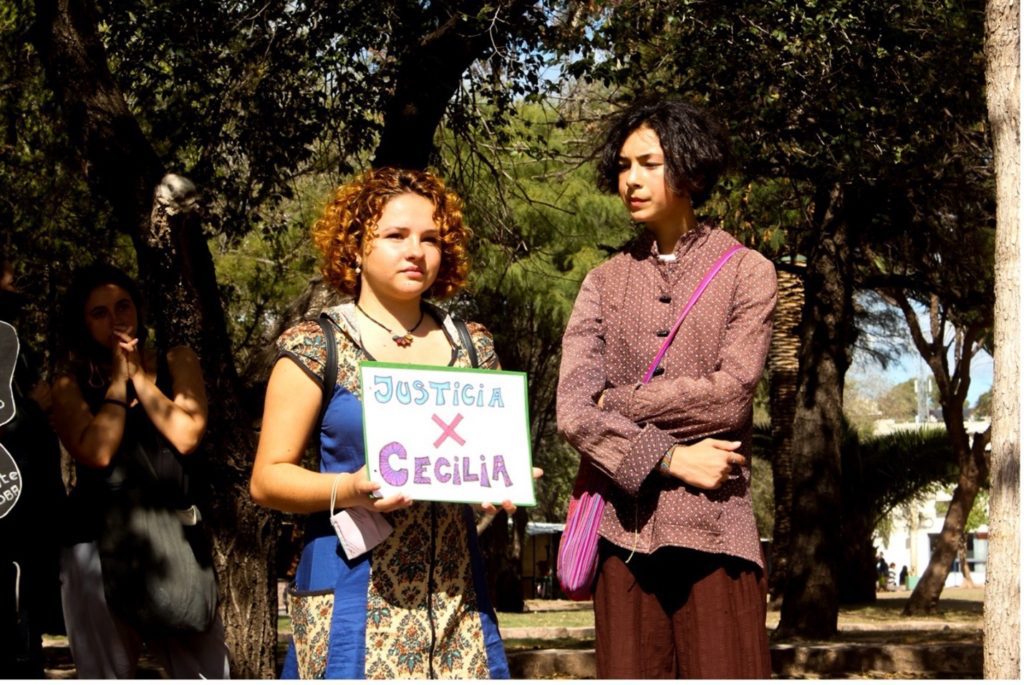

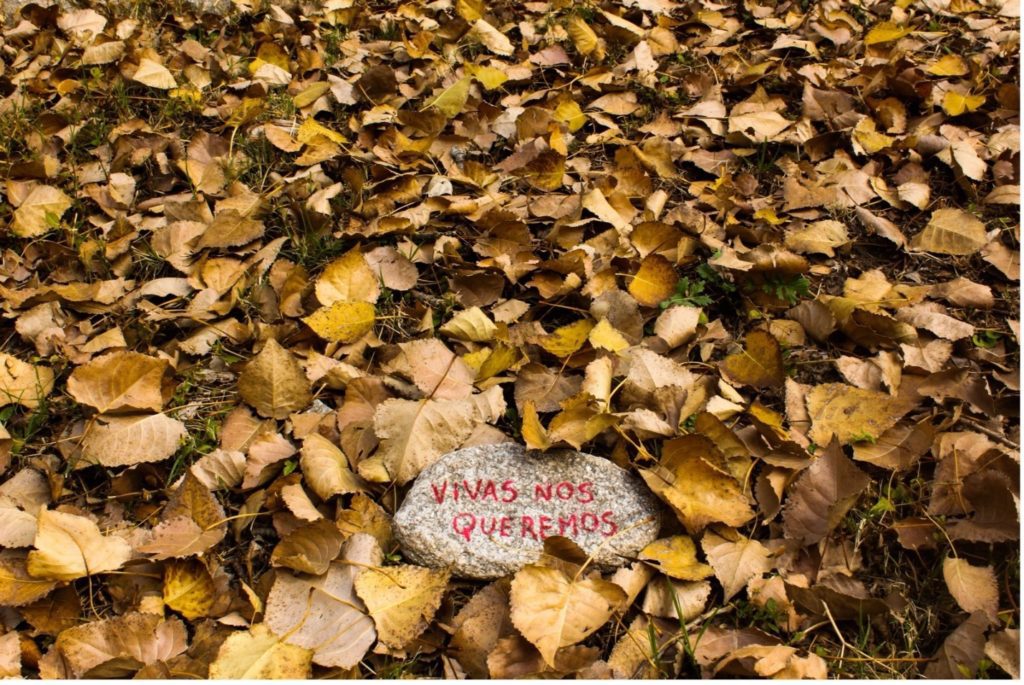

The photographs have been taken by Paz Bustamante in the following contexts:

- Mobilisation for Legal, Safe, Free Abortion, Buenos Aires, 2019.

- March for Justice for Cecilia Basaldúa, Capilla del Monte, Third Judgment to Patriarchal Justice, Capilla del Monte, Córdoba—Movimiento Plurinacional Disidente y Feminista de Capilla del Monte—Feministas del Abya Yala.

REFERENCES

Bertelli, Pino (2020), Tina Modotti: Sulla fotografia sovversiva. Dalla poetica della rivolta all’etica dell’utopia, Rimini: Interno4.

Borelli, Mauro (2021 [2007]), La fabbrica del passato. Autobiografie di militanti comunisti (1945-1956), Macerata: Quodlibet.

Cacucci, Pino (1991), Tina, Milano: Interno Giallo.

De Cortanze, Gérard (2020), Moi Tina Modotti. Heureuse parce que libre, Paris: Albin Michel.

Frida Kahlo & Tina Modotti (1983), dir. Laura Mulvey, Peter Wollen.

Hermann, Gina (2003), ‘Voices of the Vanquished: Leftist Women and the Spanish Civil War’, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 11-29.

Hooks, Margaret (1993), Tina Modotti: Photographer and Revolutionary, New York: Harper Collins.

Lowe, Sarah (1995), Tina Modotti: Photographs, New York: Abrams.

Mildred, Constantine (1983), Tina Modotti: A Fragile Life: An Illustrated Biography, New York: Rizzoli.

Modotti, Tina (1929), ‘Sobre la fotografia/On photography’, Mexico Folkways, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 196-198.

Natoli, Claudio (2017), Tina Modotti. Arte e libertá tra Europa e Americhe, Udine: Forum Edizioni.

Poniatowska, Elena (1996), Tinisima, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

Santarelli, Enzo (1973), Storia del Fascismo, Vol. 2, Roma: Editori Riuniti.

Vidali, Vittorio (1982), Ritratto di donna, Milano: Vangelista.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey