‘I’m Still Jenny from the Block’: Jennifer Lopez in Shades of Blue

by: Phoebe Macrossan , June 14, 2021

by: Phoebe Macrossan , June 14, 2021

Introduction

When we first see Puerto-Rican American actress and pop star Jennifer Lopez as the crooked New York detective Harlee Santos in the Shades of Blue (NBC 2016-2018) pilot episode (S1:E1), her hair is wet and dishevelled as she sits on her bed, looking shattered. She opens up her laptop and speaks into the camera, making a video recording for we don’t know who. ‘I always wanted to be a good cop… But there’s no straight line to that. I always told myself that the end would justify the means… But now that I’m at the end, I can’t justify anything. It happened so slowly, I didn’t realise, and so quickly, I never saw it coming’, she says. After this opening monologue, we jump back in time two weeks to a seemingly ordinary day in Santos’ life, a day in which she teaches rookie recruit Michael Loman (Dayo Okeniyi) the ropes, including covering up his own unlawful killing of an unarmed African American suspect when they force their way into an apartment, meets with her teenage daughter Christina (Sarah Jeffery) after school, and trains with a boxing coach, who she pushes to the floor and kisses before, we assume, sleeping with him afterwards. Santos leaves this causal encounter to meet up with rest of her Brooklyn squad, including her boss Matt Wozniak (Ray Liotta), to divvy up their takings from the days arrests; Santos takes a sparkly red dress for her daughter to wear at her cello recital.

These complicated and morally dubious aspects of Santos’ life create a picture of a gritty, hardworking detective, who is also a dedicated single mother and a sexually confident woman. Her acknowledgement that she ‘always wanted to be a good cop’ in her opening monologue frames this depiction with the notion that she cannot be all bad—she just got lost along the way. What cannot be erased or ignored from this establishing portrait of the series’ central character, however, is the considerable star presence of Lopez, particularly her complicated ‘J. Lo’ persona that is inflected with her Latina identity, Puerto-Rican heritage, pop star career, and the media fetishisation of her body and her supposed ‘diva’ status. Lopez started her professional life as a dancer and actor on 1990s television, including In Living Color (FOX 1990-1994), Second Chances (CBS 1993-1994), South Central (FOX 1994), and Hotel Malibu (CBS 1994), before acting in several films, including the biopic Selena (Gregory Nava 1997), and rom-coms The Wedding Planner (Adam Shankman 2001), Maid in Manhattan (Wayne Wang 2002) and Monster-in-Law (Robert Luketic 2005). However, Lopez reached international fame as the pop star ‘J. Lo,’ her self-styled moniker, and the title of her second studio album (2001).

Shades of Blue sits within a wave of female detective-led series, including The Closer (TNT, 2005-2012), Damages (FX Network, 2007-2010; Audience Network, 2011-2012), The Killing (AMC, 2011-2014), Crossing Jordan (NBC, 2001-2007), In Plain Sight (USA Network, 2008-2012), Rizzoli & Isles (TNT, 2010-), Homeland (Showtime, 2011-), and the limited series Unbelievable (Netflix 2019), among others, which have all had varying levels of commercial and critical success. The question remains then, as Jermyn puts it, ‘[w]hat do women cops need to do to make the cut in an era in which it seems, on the one hand, they are more prevalent and have more opportunities open to them than ever before; but also, on the flip side of this … in an era where the presence of a female detective in itself is no longer worthy of remark, nor an innovation or novelty in itself’? (Jermyn 2017: 260) Charlotte Brunsdon argues that the canonical feminist television studies text Prime Suspect (Granada 1991-2006) demonstrated that crime shows with female leads can be extremely successful, and the subsequent television female detectives are ‘daughters of Jane’ Tennison (played by Helen Mirren). (2013: 376) Despite Lopez’s star power, however, Shades of Blue received mediocre reviews and ratings, finishing after three seasons, and does not offer a particularly complex feminist sensibility or character study.

This article argues that elements of Lopez’s ‘J. Lo’ pop star image—namely her heteronormative desirability and extreme femininity, her sexiness, her ‘fit’ body and ample ‘booty,’ her motherhood, New York upbringing, Latina identity, and her supposed ‘diva’ status—are incorporated, in varying ways, into Harlee Santos’ own identity on Shades of Blue. In particular, this paper interrogates how J. Lo’s ‘diva’ status as a difficult woman is incorporated into her depiction of Santos as a crooked cop with a heart of gold that is ultimately tied to her role as a single mother. While pop stars have always crossed over into film and television work, some quite successfully, Lopez has made the transition from dancing to acting to singing and back again. In 2001 she became the first actress to have a movie (The Wedding Planner) and an album (J. Lo) top the charts in the same week. (Tyrangiel 2005) As a star with a notably long acting and singing career, neither of which have gone unrecognised in popular culture, Lopez and her recent performance as Harlee Santos provide a unique opportunity to examine how pop stardom and female detectives intersect in current mainstream American television.

The first section of this paper charts Lopez’s television and musical career, outlining some of the problematic constructions of both her Latina identity and the sexualisation of her body in the media. It performs a critical discourse analysis of magazine and newspaper articles about Lopez, interviews with the star herself, as well as critical textual analysis of her own social media content, including her official Instagram account. The second section performs an in-depth textual analysis of key scenes in Santos’ character arc throughout the first season of Shades of Blue, considering how these align with J. Lo’s image. For this analysis of Lopez as ‘J. Lo,’ I borrow Richard Dyer’s influential concept of the ‘star image.’ In his seminal work on film stars, Heavenly Bodies (1986: 2-3), Dyer argues that stars are polysemic images made up of multiple media texts, including all the publicity, promotion, commentary, and criticism generated about them, as well as their actual work products, the films themselves. The term ‘star image’ is therefore a useful concept for considering the way that stars are ‘overwhelmingly a product of media representation’. (Turner 2014: 8) We can expand this idea to pop stars and think of Lopez’s ‘star image’ as audiovisual—i.e., to include all audio recordings of her songs, as well as music videos and other professional concert performances. Finally, the paper concludes by considering where Lopez’s acting and musical career might take her next, and how the crime drama genre is particularly suited to her unique star power.

Section One: ‘It’s Full Body Training’: Feminine Labour and Jennifer Lopez the Puerto Rican ‘Diva’

The first central element of the ‘J. Lo’ star image to be incorporated into Santos’ character is Lopez’s Latina, and specifically hot, fit, young and sexualised, body. Lopez’s body is central to both her star image and her Latina identity. However, ‘[b]eing Latina is not an ethnicity anchored in a tangible culture and/or place’. (Lugo-Lugo 2015: 99-100) Lopez’s Latina identity is further complicated by her Puerto Rican heritage—both her parents were born there and immigrated to the Bronx in New York, where Lopez was born and grew up. As Carmen R. Lugo-Lugo argues, ‘Puerto-Ricanness’ is a racialised ethnicity rather than a racial or ethnic identity.(2015: 99) Both Lopez’s celebrity persona and her Puerto Rican identity are tied to and centred by her body, continuing the long history of fetishising and exoticising the Latina female form. As Lugo-Lugo (2015:110) continues, ‘Lopez’s body is not only the structure through which her claim to ethnicity is staked, but also the means through which her public persona has been commodified, commercialised, and marketed extensively.’ Because Peurto-Ricanness is a racialised ethnicity, the fetishisation of Lopez’s body as ‘Latina’ occurs through a racial lens.

Mary Beltran has written about the ‘realness’ of Lopez’s body when she was cast as a ‘Fly Girl’ on the 1990s sketch comedy show In Living Color. This casting was ‘fitting a show targeting the ‘urban’ demographic’ where ‘urban’ is a particularly racialised non-white identity. (Beltran 2009: 136) Unlike other sketch comedy shows at the time, In Living Color featured several stars of colour, including the Wayan Brothers, Jamie Foxx and David Alan Grier. The media frenzy and fetishisation of Lopez’s Latina body has been particularly focused on her buttocks, as reams of media copy have been dedicated to this area—including suggestions that a revealing photograph of her behind in Vanity Fair in 1998 ‘changed the world’. (Kennedy 2010 ) Indeed, Lopez caused significant media discussion of her ample booty years before the racialised discussion of reality television star Kim Kardashian’s curvaceous behind. Like Lopez, Kardashian’s body simultaneously reinforces ‘heteronormative structures of reproductive, privatised sexuality and a historic racial dichotomy that positions white bodies as refined and restrained’ and non-white bodies ‘as overtly sexual … while exploiting the interstices of such taxonomies for profit’. (Sastre 2013: 124) Like Kardashian, Lopez has embraced and perpetuated this commodification of her own body, even releasing a song and music video with pop star Iggy Azalea titled ‘Booty’ in 2014. [1]

Another central facet of Lopez’s star narrative incorporated into Santos’ character is her hardworking attitude. Lopez has long spoken about her struggles as an up-and-coming actress and dancer in the 1990s, and has frequently linked these struggles to those of her parents and their story of immigration to America. As Lockhart writes, ‘Lopez is constructed as hard working and focused, characteristics that, when joined to her natural talent and charisma, have aided her in realising not only her own dreams but also a particular version of the ethnic-American Dream’. (2007: 153) This hard-working ethic, and the struggling Latina single mum character she plays in Shades of Blue therefore overlap effectively. Lopez’s own struggles to pursue the American Dream inform Shades of Blue’s depiction of Santos’ struggles with daily police work and being a single mum, including her many moral and ethical dilemmas.

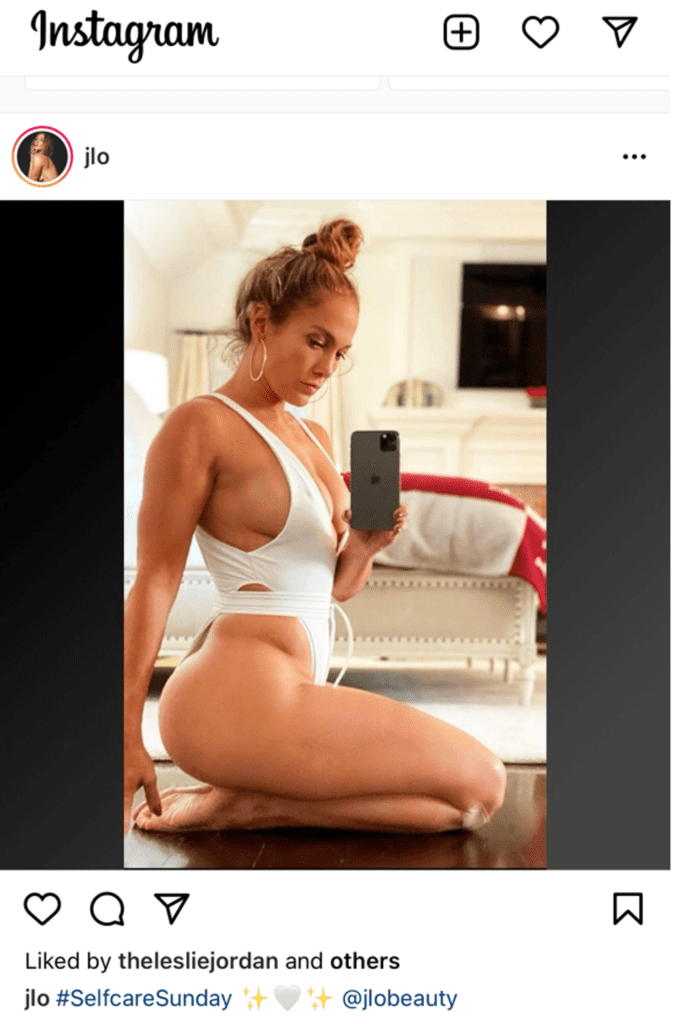

This hard work for both Lopez and Santos includes an extreme amount of working out—we quite literally see Santos boxing into a sweat in the pilot. Lopez herself constantly emphasises she has worked hard, and continues do so for the sake of both her career and her body—fitness is a key part of her star image. Her Instagram page, for example, arguably the most direct method of fan-star relationships in the current era, is updated with her exercise workout routines and tips, as well as hundreds of bikini shots that emphasise her ample ‘booty’—commodifying her own behind. (See Figures 1 & 2 above) Lopez also posted a 13-minute YouTube video featuring her intensive pole dance training for her role as stripper Ramona in Hustlers [2], and has previously outlined an extensive fitness regime:

I freestyle dance with Tracy Anderson five times a week. We’ll incorporate light weights … for the arms, and moves that focus on the butt and thighs and engage the core … I also do circuit training with David Kirsch when I’m in New York. We do hour-long circuits at least three times a week. Its full-body training—so planks, push ups, boxing—really everything. (quoted. in Fields 2016)

This intensive level of exercise is really only possible for a high-profile star with the economic means to pay a personal trainer and have the extended time to dedicate to fitness. It is not just Lopez’s labour in maintaining her star image, but also the intense work of the team behind her: dieticians, personal trainers, beauticians, hair stylists, personal chefs, and so on. Thus the extreme fitness required to be ‘J.Lo’ highlights the unrealistic standards of beauty placed upon all women—though particularly women of colour—through celebrity narratives.

More recently, Lopez’s lack of visible signs of aging has also received much media attention, as has the feminine labour that must go into maintaining her ‘hot’—heterosexually desirable, heteronormative, fit and muscular—body. (Ivie 2018; Capon 2020) For example, Dana Wood writes that:

This is a former ‘Fly Girl’ who just delivered an entirely plausible performance as a stripper in 2019’s ‘Hustlers,’ then imported an iteration of her trusty pole to the 2020 Super Bowl half-time show and, Spandex-clad, stunned viewers with her gyrations. You don’t do either of those things at ages 49 and 50, respectively, without a mammoth amount of prep, and, in Ms. Lopez’s case, years of herculean determination to stay not just youthful, but stripper-hot. (2020)

Publicity material about Lopez, particularly in glossy magazines, will often focus on Lopez’s workout regime in order to sell issues to readers who want to know how she maintains her desirable body. (Clark 2020; Fields 2016)

Both Lopez’s own star image, and the publicity surrounding her, emphasises the labour it takes not only to be a successful actress and pop star, but also to meet the current Western standards of beauty placed on women, primarily extreme physical fitness and the appearance of youth. However, as Radner points out, ‘as a Latina star, Lopez represented a new world order of femininity in which the ability to ‘look good’ and work hard, and thus, incarnate the ideals of the female ‘striver,’ became available to a broader demographic of women’. (Radner 2011: 5) Lopez’s hardened detective Santos in Shades of Blue chases down suspects in jeans, sneakers, baggy pants and loose tops, but still manages to have a full face of glamourous makeup that is familiar and in keeping with her J. Lo image. We never see Santos apply this makeup, however, and nor do we see her take it off or put on any face cream, or any other form of beauty maintenance. Even Santos’ hair, a shoulder-length, dark brown, very curly mop, is reminiscent of her Fly Girl audition tape (readily available on YouTube [3]). These costuming, hair and makeup choices add to the layering of the Lopez/Santos persona, bringing in extra-diegetic references to Lopez’s long career in the public eye.

The trouble with the costuming and makeup choices for Santos/Lopez is not only that they must make direct reference to Lopez’s long career in order to carry all the other characterisations associated with the star, but that at the same time Santos cannot be too hot, too fit, too glamorous, so as to distract the viewer and make the show implausible. This is because, as Jermyn argues, ‘the media’s constant return to the women protagonists’ ‘appropriate’ or ‘inappropriate’ sartorial choices crystallises the inescapably gendered nature of the reception of these female detectives, one which situates them within generic traditions but also operates to contain them within a ‘feminine’ realm’. (Jermyn 2017: 265) This is perhaps, as Rosalind Gill argues, inherent of a postfeminist media culture that still overwhelmingly expects women’s adherence to normative standards of femininity, and ideally their willing subjectification of the self. (2007) Hence, we might ask: ‘what a woman cop might do in today’s postfeminist media landscape to maximise her chances of staying on-screen?’ (Jermyn 2017: 260)

Santos must be both tough, hardworking, serious, and good at her job, while maintaining the ‘stripper hot’ J. Lo image of a sexually empowered woman. This is typical of postfeminist media culture, where, Angela McRobbie argues, an ‘individual choice’ rhetoric is central, whereby feminist-inflected words like ‘empowerment’ and ‘choice’ are used to create individual-focused discourses as a substitute for substantive socialist feminist politics. (11-12) Gill argues that ‘what makes contemporary media culture distinctively postfeminist … is precisely this entanglement of feminist and anti-feminist ideas’ (2007: 161), or what McRobbie calls the ‘double entanglement’ of femininity with both traditional and liberalising agendas in ‘the aftermath of feminism’. (2007: 255) Santos must be confident and chase down suspects in the dirty streets of the New York while wearing a similar amount of makeup as ‘J. Lo’ would in a music video.

Section Two: Harlee Santos and the Bronx: Breaking Down and Building Up Lopez as a Gritty, Troubled Cop

Santos is a dirty cop among a team of dirty cops, and we are always aware of her switching moral compass. It is set up early in the series that she has framed her ex-boyfriend Miguel Zepeda (Antonio Jaramillo) for murder in order to escape his violent behaviour. Her entire detective team takes payoffs from local shopkeepers for extra protection, while keeping opposing drug syndicates happy within their neighbourhood beats. When her daughter’s boyfriend is arrested by her team for accidentally breaking a police car tail-light, Santos physically assaults him in the investigating room when she discovers photos of her daughter on his phone (S01E05). This illustrates how she code switches from protective mother to aggressive and heavy-handed cop.

Shades of Blue also switches between gritty police narratives and the melodrama of Santos’ personal life. In her analysis of the film noir genre and the female detective, Philipa Gates (2009: 24) argues that ‘the narrative is driven forward as much by the female protagonist’s personal desires familiar in many types of melodrama (specifically the woman’s film) as by her investigation, which usually drives the narrative of a detective film.’ This blurring of melodrama, or at least drama and crime series, is also evident in Shades of Blue, which is driven as much by the ongoing police procedural dramas of Santos’ crooked team—Wozniak’s mishandling of two drug lords’ merchandise, Loman’s guilt over mistakenly shooting and killing a black suspect, and her colleague Tess Nazario’s (Drea de Matteo) attempts to move a dead body—as it is by Santos’ personal motivations. Santos sleeps with Assistant District Attorney James Nava (Gino Anthony Pesi) while flirting with her FBI handler Special Agent Robert Stahl (Warren Kole), who is listening to everything via an earpiece. We might also consider how female cops, women in power, and women in general are also largely defined or understood through their personal lives in ways that men are not; thus, Santos’ role as a mother becomes all-encompassing and drives her police work.

Santos’ characterisation as a hard-edged New York cop with a heart of gold is filled out by Lopez’s status as ‘Jenny from the Block’—the title of the lead single from her third studio album This is Me… Then (2002). The song and music video attempt to frame Lopez as remaining in touch with her humble Bronx upbringing, despite the fame and fortune she has received. In a recent interview, Lopez continues to craft this narrative of the tough girl attitude:

I think, growing up in the Bronx, there’s a little bit of a, you know, urban-gangster quality. That ‘Jenny From the Block’ side. With my Timberlands and my hoops. ‘Cause we came from such a hard kind of background in that way. Growing up on those types of streets, I used to see girls fighting. I grew up with that. And it affects you. It makes you a little bit of a tough, badass type character. When I went to L.A., everybody seemed so soft. (quoted in Pressler 2019)

The ‘Jenny from the Block’ music video is also a key text in the J. Lo star narrative, as it courted controversy at the time through featuring her then boyfriend—later fiancée—Ben Affleck. The video directly comments on the excessive media interest in their relationship, as it shows the pair in a series of intimate settings, all seen through the paparazzi lens. This excessive media interest has been attributed to the fact that Affleck and Lopez dated in the early 2000s, when celebrity tabloids like People and Us Weekly were contending with the rise of the internet. (Litman et al 2019) This relationship and its subsequent demise also formed a key part of Lopez’s characterisation as a ‘diva,’ due in part to her supposed demands on Affleck and her staff, as well as the size of her $2.5 million 6-carat pink diamond engagement ring. (Barbour 2020 & Wolton 2019) The ‘diva’ characterisation is something Lopez rejects, and she has rightly noted its racist and sexist undertones. Speaking about the time period in a recent interview she has said: ‘I was Latin, and I was a woman, and I was Puerto Rican, and they were not giving me the same pass that they gave everybody else at certain times’. (quoted in Pressler 2019 )

While Santos’ hard edge draws on the ‘Jenny from the Block’ and ‘diva’ aspects of J.Lo’s star image, it is countered by both star and character’s caring, kind and supportive side. Santos gets Caddie (Michael Laurence), her former training manager, out on bail, only to ask him to install surveillance cameras in FBI Agent Stahl’s apartment. Later in the episode, she offers to take him to, and pay for, a rehab centre, as he shoots up heroin on a rooftop (S01E05). When she pleads with him, ‘How long since you’ve done 20 days?’ he responds, ‘How long since you’ve been honest?’ The show neatly builds intrigue and suspense for the viewer in Santos’ double-dealings, yet encourages empathy for her as a likeable yet troubled character—a conflicted antihero. Jason Mittell defines the antihero as ‘a character who is our primary point of ongoing narrative alignment but whose behavior [sic] and beliefs provoke ambiguous, conflicted, or negative moral allegiance’: (2015: 142–143) As other scholars have noted, the appeal of the television antihero is usually tied up with displays of extreme violence and toxic masculinity, as with Tony Soprano of The Sopranos (HBO 1999-2007) and Walter White of Breaking Bad (AMC 2008-2013). (Rosenberg 2013; Lotz 2014; Vaage 2015; Albrecht 2016; Hagelin & Silverman 2017) This is particularly true for the rogue cop who works for the greater good within the police system. As Hagelin and Silverman argue, ‘because police procedurals feature antiheroes working in the service of law enforcement rather than criminality, audiences are perhaps even more willing to give toxic masculinity a pass, since it is pursued in the name of a greater justice’. (2017: 851-2) Mittell writes that there are few female antiheroes who sustain the level of audience engagement required of the definition. (2015: 149–150) This observation is challenged, not just by the rise of female antiheroes in recent television drama—Circe from Game of Thrones (HBO 2011-2019), Hannah from Girls (HBO 2012-2017), Cookie from Empire (FOX 2015-2020), Claire Underwood from House of Cards (Netflix 2013-2018) to name a few—but also by the antihero female detective Santos.

As a female cop antihero, Santos ‘reveals the extent to which audiences mistakenly equate hypermasculinity with autonomy and independence,’ because she provides an alternative matriarchal and feminine power that challenges the system. (Hagelin & Silverman 2017: 852) We want to believe that ‘the [male] antihero’s hypermasculinity both challenges state power and leads to a more righteous society—and that our own enjoyment of his exploits grows out of a similar impulse for non-conformity and social remediation’. (Hagelin & Silverman 2017: 853) Santos, by contrast, provides a form of matriarchal and feminine power that is anchored by her status as a single mother, because her daughter forms the central moral and ethical justification for her decisions. Once Caddie has shot up his heroin, Santos muses to him: ‘I thought I knew whose side I was on, now I don’t know who to trust. And I hate them both for taking that away from me. All I know is that when Christina finds out who I really am, I’m going to lose her’ (S1E5). This characterisation taps into more recent iterations of Lopez’s star image, namely her own role as a mother.

Santos’ key drive to protect and nurture her daughter is heightened by Lopez’s own explicit performance of loving motherhood on Instagram and other social media platforms. Lopez’s role as a mother is a key part of her stardom, just as Santos’ job as a cop is centred around her love for her daughter Christina. Lopez has 13-year-old twins —a boy Max, and a girl, Emme—with ex-husband Marc Anthony. Singing, dancing and goofing around with her kids form several videos on her Instagram and Twitter feeds, including posting intimate family shots with them on holiday, at home, and with her fiancée, professional baseball player Alex Rodriguez. I say ‘performance of loving motherhood’ because, like most contemporary pop stars, Lopez uses social media to craft narratives of sincerity and authenticity around her stardom. Academic and popular discourse around fame, stardom, and celebrity is also often framed through the lens of ‘authenticity.’ For example, P. David Marshall posits that popular music celebrity relies on a dichotomy between ‘authenticity’ and ‘inauthenticity’. (1997: 150) Dyer argues a central appeal of the star is discovering who they ‘really’ are, the essence of their individual nature behind their work or public image. (1986: 2) ‘Sincerity’ and ‘authenticity’ are ‘greatly prized in stars’ because they guarantee that the star really is what they appear to be and really means what they say, respectively. (Dyer 1979: 3) This desire to appear sincere, authentic and ‘ordinary’ has long driven J.Lo’s star narrative, as is evidenced by her lyrics: Don’t be fooled by the rocks that I got/I’m still, I’m still Jenny from the block. (Lopez 2002)

Ultimately, Santos’ performance of matriarchal and feminine power leads to her downfall. She fails in her attempt to protect Christina from her criminal and abusive father, Miguel. Angry that her mother has lied to her, Christina runs away with Miguel to spite her. Santos’ mentoring of the rookie Loman also backfires, as by the finale of Season One he is also covering up his own unlawful killing of Donnie Pomp (Michael Esper), Wozniak’s gay lover, and an internal investigation officer attempting to blackmail the team. Santos makes a self-sacrificial deal with FBI special agent Stahl to trade her own immunity in exchange for her crew’s freedom. ‘Why not run?’ Stahl asks her. ‘I thought about it. Then I thought about the message I’d be sending to my daughter. How is she ever going to take responsibility for her mistakes if I don’t?’ Santos replies (S01E13). While at this moment she sends Christina away to live with her aunt, thinking she will be spending several years in jail, the season ends with Santos breaking Miguel’s neck after he breaks into her apartment and attempts to rape her at gunpoint. This murder continues the moral dilemmas and double crossings of the subsequent seasons, as Santos’ drive to protect her daughter leads her further into a life of crime.

Conclusion

Harlee Santos in Shades of Blue was perhaps the tentative first act of Lopez’s renewed resurgence in popular culture, as since then J.Lo’s stardom has reached something of a critical mass, or what some have termed a ‘major career renaissance’. (Vanderhoof 2019) In 2019, she produced and played one of the leading roles as a con-artist stripper in Hustlers (Lorene Scafaria), and in contrast to Shades of Blue, earned nominations for Best Supporting Actress at the Golden Globe Awards, Screen Actors Guild Awards, Critics’ Choice Movie Awards and Independent Spirit Awards. Lopez also modelled a version of the extremely low-cut green Versace dress that caused a media storm in 2000 when she originally wore it to the Grammys—the 2019 appearance focused on her ability to ‘defy time,’ in that the 50-year-old Lopez looked just as good as the 30-year-old. (Vanderhoof 2019) In February 2020, she co-headlined the Superbowl halftime show (considered a key sign you have made it to super pop stardom) with Columbian singer Shakira. She then performed on the coveted New Year’s Eve show at Times Square in New York City, and in January 2021 she performed at President Joe Biden’s inauguration ceremony, singing the American folk classic ‘This Land is Your Land’ by Woody Guthrie, addressing the audience partly in Spanish.

As I have outlined above, the series clearly drew on key aspects of Lopez’s star narrative as ‘J. Lo’ to inform the characteristics and narrative arc of Harlee Santos—her Latina and Puerto-Rican identity and hardworking migrant background, her Bronx upbringing and subsequent ‘Jenny from the Block’ tough girl attitude, and her hyper-sexualised and uber-fit bodily performance of heteronormative sexuality and beauty. It is hampered however, by its adherence to postfeminist media culture expectations of feminine beauty, limited matriarchal power and individual empowering choices—choices which ultimately end with Santos in an orange jumpsuit in front a judge, punished for her struggles.

Notes:

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nxtIRArhVD4&ab_channel=JenniferLopezVEVO (last accessed 5 May 2021).

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRhOWrk5_NM&ab_channel=JenniferLopez (last accessed 5 May 2021).

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=51pTRzh4CrQ (last accessed 5 May 2021).

REFERENCES

Albrecht, Michael (2016), Masculinity in Contemporary Quality Television, New York: Routledge.

Barbour, Shannon (2020), ‘Jennifer Lopez Gushed About Her Old $2.5 Million Engagement Ring From Ben Affleck: Lucky for A-Rod, Her Love Don’t Cost a Thing’, Cosmopolitan, 22 April 2020, https://www.cosmopolitan.com/entertainment/celebs/a32238347/

jennifer-lopez-engagement-ring-ben-affleck-alex-rodriguez/ (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Beltran, Mary (2009), Latina/ Stars in U.S. Eyes: The Making and Meaning of Film and TV Stardom, Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Boorstin, Daniel J. (1971), The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, New York: Atheneum. (Originally published in 1961 as The Image; or What Happened to the American Dream?).

Brunsdon, Charlotte (2013), ‘Television Crime Series, Women Police, and Fuddy-duddy Feminism’, Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3. pp. 375-394.

Capon, Laura (2020), ‘16 ways Jennifer Lopez makes 51 look 31’, Cosmopolitan, 23 November 2020. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/celebrity-hair-makeup/g10385940/jennifer-lopez-age/ (last accessed 5 May 2020).

Clark, Lucie (2020), ‘This is how Jennifer Lopez makes your 50s look like the new 20s’, Vogue, 18 November 2020. https://www.vogue.com.au/beauty/news/this-is-how-jennifer-lopez-makes-50-look-like-the-new-25/image-gallery/a1f9076d9ca12cb7f8fb5b871b8716c9 (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Dyer, Richard (1979), Stars, London: British Film Institute.

Dyer, Richard (1986), Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, London: Macmillan Education.

Fields, Jackie (2016), ‘Jennifer Lopez Spills Her Secrets for Looking Like a Perfect 10 at Age 46: ‘It’s Hard Work!’’, People, 4 February 2016, https://people.com/style/jennifer-lopez-spills-her-secrets-for-looking-like-a-perfect-10-at-age-46-its-hard-work/ (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Gates, Philippa (2009), ‘The Maritorious Melodrama: Film Noir with a Female Detective.’ Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 61, No.3. pp. 24-39.

Gill, Rosalind (2007), ‘Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 147–166.

Hagelin, Sarah & Gillian Silverman (2017), ‘The Female Antihero and Police Power in FX’s Justified’, Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 851-865, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1283344

Ivie, Devon (2018), ‘Even Jennifer Lopez Is Confused by How Little She’s Aging’, W Magazine, 31 May 2018, https://www.wmagazine.com/story/jennifer-lopez-aging/ (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Kennedy, Erica (2010), ‘How J. Lo’s Ass Changed the World’, Huffington Post, 25 May 2010, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/how-j-los-ass-changed-the_b_586226 (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Litman. Juliet, Amanda Dobbins & Amelia Wedemeyer (2019), ‘Revisiting Bennifer 1.0 and Tabloids at the Turn of the Century’, Ringer Dish Podcast S01, E01, 4 June 2019, theringer.com/2019/6/4/18651970/revisiting-bennifer-1-0-and-tabloids-at-the-turn-of-the-century (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Lockhart, Tara (2007), ‘Jennifer Lopez: The New Wave of Border Crossing’, in Myra Mendible (ed.), From Bananas to Buttocks: The Latina Body in Popular Film and Culture, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Lotz, Amanda (2014), Cable Guys: Television and Masculinities in the 21st Century, New York: New York University Press.

Lugo-Lugo, Carmen R (2015), ‘100% Puerto Rican: Jennifer Lopez, Latinidad, and the Marketing of Authenticity’, Centro Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 96-119.

Marshall, P. David (1997), Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture, Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press.

McRobbie, Angela (2007), ‘Post-feminism and Popular Culture’, Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 255–264.

Mittell, Jason (2015), Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling, New York: New York University Press.

Pressler, Jessica (2019), ‘The High-Powered Hustle of Jennifer Lopez’, GQ, 18 November 2019, https://www.gq.com/story/jennifer-lopez-icon-of-the-year-2019 (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Radner, Hilary (2011), Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks and Consumer Culture, New York: Routledge.

Redmond, Sean & Su Holmes (2007), ‘Introduction: What’s in a Reader?’, in Sean Redmond & Su Holmes (eds), Stardom and Celebrity: A Reader, London: SAGE, pp. 1-11.

Rosenberg, Alyssa (2013), ‘Why We’ll Never Have a Female Tony Soprano’, Slate Magazine, 6 June 2013, http://www.slate.com/blogs/xx_factor/2013/06/27/james_gandolfini_and_the_male_anti_hero_why_we_ll_never_have_a_female_tony.html (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Sastre, Alexandra (2013), ‘Hottentot in the Age of Reality TV: Sexuality, Race, and Kim Kardashian’s Visible Body’, Celebrity Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1-2, pp. 123‒137.

Turner, Graeme (2014), Understanding Celebrity (2nd ed.), London: SAGE.

Tyrangiel, Josh (2005), ‘Jennifer Lopez’, Time, 13 August 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20090301064251/http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0%2C8599%2C1093638%2C00.html (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Vaage, Margrethe Bruun (2015), The Antihero in American Television, New York: Routledge.

Vanderhoof, Erin (2019), ‘Jennifer Lopez’s Reprised Green Versace Dress Deserves Its Own Oscar Buzz’, Vanity Fair, 20 September 2019, https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2019/09/jennifer-lopez-green-versace-milan-spring-2020 (last accessed 5 May 2021).

Wolton, Rebbekka (2019), ‘Some of the most ‘diva’ demands Jennifer Lopez has reportedly made’, Social Gazetta, 24 March 2019, https://socialgazette.com/stories/diva-demands-jennifer-lopez-reportedly-made/(last accessed 5 May 2021).

Wood, Dana (2020), ‘Can Women Really Look Like Jennifer Lopez at 50?’, Wall Street Journal, 12 March 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/can-women-really-look-like-jennifer-lopez-at-50-11584042051 (last accessed 5 May 2021).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey