Breaking Glass: Reclaiming Harley Quinn’s Past to Determine her Feminist Future

by: Sam Langsdale , March 30, 2023

by: Sam Langsdale , March 30, 2023

Harley Quinn, a character created for DC Comics media, was originally intended as nothing more than a token-female goon in the gang of the notable supervillain, the Joker. Created in 1992 by Paul Dini and Bruce Timm for Batman: The Animated Series (BTAS), Harley received unexpected amounts of attention from fans and so became a mainstay in the animated show. She evolved from the status of one goon among many to the Joker’s sidekick and love interest, and eventually, as she made her way into other DC media like comic books, enjoyed fame as a supervillain in her own right. Nevertheless, Harley’s rise to becoming one of DC’s most popular and recognisable characters was hardly a feminist success story. As numerous scholars have noted, Harley’s origins and subsequent treatment across media were deeply problematic, centring on unrequited love for the Joker, his physical, mental, and emotional abuse of her, and the increased sexualization of her character that sedimented her as an object of male control. Even as later comics creators attempted to retell Harley’s story in ways that ameliorated the violence of her original iterations, and even as fans found creative ways to interpret her circumstances in order that she could be read as a role model for girls and women, Harley’s trajectory was still inextricably tied to the harmful patriarchal norms and biases that had framed her creation. Stating this is not to undermine the changes creators of comics, toys, and animation have made to Harley in the last decade, which have undoubtedly pushed the character in more progressive directions. However, in this article I argue that few Harley comics have revised the character in such thoroughly feminist [1] ways as the retcon graphic novel Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass (2019) by writer Mariko Tamaki and artist Steve Pugh.

According to Elizabeth Rae Coody, ‘origin stories are never innocent,’ and in patriarchal cultures, they are often written in ways that ‘explain away or undercut women’s agency,’ but when feminist creators retell origin stories, it offers ‘a chance to reclaim that power’ (Coody 2020: 15-17). It is precisely through telling Harley’s origins anew that Tamaki and Pugh assure her a more feminist future. Set in Harley’s early teens, Breaking Glass imagines the antiheroine arriving in Gotham City after a childhood full of poverty, familial strife, and an already long rap sheet. The book queers the conventions of the superhero genre as Harley becomes part of a found family, begins a life-altering friendship, and learns that systemic injustice cannot be solved by blowing stuff up. As part of DC’s imprint for young adults, Breaking Glass leans into its pedagogical power by demonstrating the intersectional failures of white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal, heteronormative societies as they manifest in high school, in a neighbourhood undergoing gentrification, and in a justice system easily manipulated by the wealthy. Harley must learn how to deal with inequity in ways that go beyond smashing windows—although she does that too. Covering both the narrative and visual content, this article analyses the intersectional strengths of Breaking Glass and concludes that the version of Harley presented by Tamaki and Pugh not only lays the groundwork for a more feminist rendition of the character going forward, but also gives young adult readers accessible ways to connect to real feminist praxis.

Harley’s History

Over the course of Harley’s 30-year existence, her origins—as a villainous sidekick, as a superpowered woman, and as an object of sexual desire—have persistently been the source of dismay for feminist fans and critics. I will begin with a brief outline of these three aspects of her genesis in order to make clear the radical shifts Tamaki and Pugh achieve in Breaking Glass. As mentioned above, Harley began as a colourful sidekick in an animated series, and then in 1993 made the transition into comic books. In 1994, co-creators Dini and Timm composed her first origin story in the single-issue comic The Batman Adventures: Mad Love. Readers were introduced to Dr. Harleen Quinzel, a young, attractive white woman starting her career as a psychiatrist at Arkham Asylum, the notorious mental institution in which Batman’s most dangerous foes are confined. Harleen begins working with Batman’s primary antagonist, the Joker, and through his manipulation and lies falls in love with him. After the Joker is physically brutalised by Batman following a failed escape, Harleen is pushed into villainy in order to break the Joker out of Arkham and begin a life of crime by his side. At one point during the breakout, Harleen reintroduces her new criminal persona as ‘Harley Quinn,’ a name the Joker fashioned for her by rearranging the letters of her name (Dini and Timm 1994). Two things become clear in this first, and most widely accepted story: one, that Harley’s origin arises out of Harleen’s descent into madness, and two, that there is ‘a meaning behind her madness’ (Owens 2017). That is, Harley’s choice to become a villain is anchored in her love for a psychopathic criminal who manipulated her into believing that he was a victim who needed her care.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. Because Harley’s relationship to Joker throughout BTAS involves myriad instances in which he physically and emotionally abuses her, Harley’s belief that the Joker himself suffers from a history of abuse and her determination to save him from it—no matter the personal cost—acts as a kind of retroactive justification of the violence. As Joe Cruz and Lars Stoltzfus-Brown argue, ‘Harley Quinn’s characterisation in BTAS perpetuates ideologies … that women are not hurt by abuse, and that violent men are endlessly attractive’ (2020: 204-5). Moreover, Cruz and Stoltzfus-Brown note that these abuses ‘often employed humorous elements such as fights inspired by slapstick comedy, which trivialises abuse’ (2020: 209). This story also heavily implies that the Joker creates Harley Quinn not only in the act of naming her, but in manipulating Harleen Quinzel’s feelings of love and empathy in order to drive her to the breaking point. The duality that emerges points to the reality that Harleen and Harley are two aspects of the same woman that have been exploited and weaponised by male creators to serve the purposes of a main male character. Some fans and scholars have tried to negotiate the tensions around Harley’s twoness by emphasising the fact that she chooses to break from her ‘normal’ life in order to pursue one with the Joker (Roddy 2011). However, this kind of argument obscures how manipulation and abuse delimit what choices are available to victims. Further, it erases the Joker’s culpability, implying instead (even if inadvertently) ‘that in following their goals and desires, female readers will also set their own demise into action’ (Jackson 2017). This last point is made clear when one considers the end of the Mad Love storyline. In response to seeing that Harley has done something he has never been capable of—capturing and incapacitating Batman—the Joker becomes furious and throws Harley out of a window into an alley far below. Even her own near-death cannot bring Harley to face the truth that the Joker is a violent abuser. On the final page of the story, Harley is wheeled back into Arkham, badly injured and in bandages. Before she can finish swearing off seeing the Joker again, she catches sight of a rose he has left her with a get well note. She changes her sentiment to say that being treated so violently ‘felt like a kiss’ (Dini & Timm 1994).

How Harley could survive such a fall is another important aspect of the many origin stories she has been assigned over the last three decades. In addition to determining how Harley Quinn came to be (both as Harley and as a criminal), creators have sought to explain her superstrength, resilience, and gymnastic acumen. In the comic Batman: Harley Quinn, Harley’s powers result from a concoction given to her by Poison Ivy, another female supervillain in Gotham (Dini, Guichet & Sowd 1999). Ivy gives Harley the superstrength potion because Harley has been shot out of a rocket by a vengeful Joker and is once again near death. Refreshingly, Ivy’s care forms the basis of a strong friendship between the two women that is developed by later creators into romantic and erotic love. That said, there is still a troubling consistency in the ways Harley’s origins are forged via heteronormative patriarchal violence. In this case, her superhuman abilities are coupled with her attempted murder by the man she purports to love. This kind of androcentric storytelling is taken to an extreme in another retelling of Harley’s origins in Suicide Squad volume 4, no. 7 (Glass, Henry & Guara 2012). Owens explains, ‘Rather than Harley choosing to take on the role of Joker’s sidekick on her own, Joker brings her to the site of his own origin, ACE Chemicals, and pushes her into a vat of chemicals to replicate his own “birth,” as he puts it, against her will’ (2017). Harley emerges with superhuman abilities, but her physical appearance is also changed to mirror the Joker’s insofar as her skin is bleached white and the ends of her blonde hair become brightly coloured. Although writer Adam Glass considered this reboot a way to enable Harley to become her own person (Owens 2017), he did so in ways that further entrenched misogynistic violence into her origins and, paradoxically, that ensured that Harley’s story would be incomprehensible without the Joker (as paramour and abuser) at the heart of it.

Harley’s appearance changed not only to signify her rebirth in the Joker’s image, but it also became increasingly sexualised over the years. In her first appearance in BTAS, Harley appeared in a black, red, and white bodysuit, jester’s hat, and white collar, all evocative of the symbolism of the joker in a deck of cards. Although her shape is normatively feminine (i.e., she has an hour-glass figure), her outfit covers her whole body; is evocative of her role as a funny sidekick, and ‘seems to put her in the position of the harlequin to the Joker’ (Wigard 2017). By the time she makes an appearance in her first video game, however, Harley’s look had drastically changed. The 2009 game Batman: Arkham Asylum featured Harley clad in a barely-there nurse’s uniform that, like many female superhero costumes, seemed to be ‘designed to reveal as much skin as possible’ (Wigard 2017). This shift was controversial amongst feminist fans, but it hardly seemed to deter DC creators. Two years later, as a part of DC’s line-wide reboot entitled ‘the New 52,’ Owens describes Harley appearing ‘on the cover with a nonsensical as well as impractical corset and shorts,’ reigniting the controversies around her increasing sexualization, and confirming some fans’ fears that Harley was being turned into an object for the male gaze (2017). On the one hand, this visual evolution is not unique to Harley Quinn. As Justin Wigard suggests, ‘superhero narratives have a long and sordid history of depicting women in sexist, objectifying manners’ (2017). On the other hand, it is important to note how these kinds of artistic changes were made possible by the history of Harley as a sexual(ised) subject.

In her first origin story, created by Dini and Timm, Harley is shown seducing her male psychology professors in exchange for good grades, implying that her success is not actually the result of her scholastic aptitude (1994). This sets Harley up in stereotypically sexist ways as a woman who uses and weaponises her sexuality in order to get what she wants. Harley also uses her sexuality to try to lure the Joker away from his pursuit of Batman, and in numerous instances her advances are met with rejection, humiliation, and physical violence. Again, scholars such as Roddy and Jackson, have suggested that because Harley chooses to use her sexuality as a kind of currency or tool, she may still be interpreted as an agential sexual subject. Creators too have tried to lean on choice as an amelioration of the ways Harley’s sexuality has formed the basis for her objectification. For example, Jackson points towards Amanda Conner, Jimmy Palmiotti, and Stéphane Roux’s comic Secret Origins, no. 4: Harley Quinn (2014). In it, Harley retells the story of her first meeting with the Joker and rather than being overcome by his seduction, Harley states that she manipulated the Joker by ‘playing along’ with his desires. She realizes that she can be anything a man wants, ‘the sex kitten, the seductress, the innocent,’ but what the Joker loves most is ‘the ditz,’ so Harley fashions herself accordingly in order to win him over (Conner, Palmiotti & Roux 2014). Jackson reads this as a return of Harley’s autonomy: ‘[r]ather than sacrificing herself in order to appeal to male sexual desires, Harley is empowered, presented as taking control of her sexuality and using it in order to manipulate the Joker and fulfil her own desires’ (2017). Unfortunately, I find such interpretations untenable. Focusing on the act of choosing does make it possible to see Harley’s agency, i.e., she is someone who consciously, deliberately acts. However, these readings of Harley’s origins arguably evoke a kind of ‘choice feminism’ that suggests that in the very act of choosing, women are empowered and politically justified in their choices, even if those choices do nothing to disrupt, and may even perpetuate, social systems of oppression (Thwaites 2017). If Harley’s choices still result in her rejection, humiliation, and near-death, and if her sexuality is still presented in stereotypically misogynistic ways, can we really claim those choices as empowering or liberatory from a feminist perspective? I suggest that in Harley’s case, reinterpreting her origins as they were established from 1992-2019 is insufficient. It is only through reclaiming the power to tell origin stories anew that Harley’s feminist potential truly unfolds, and that is precisely what Mariko Tamaki and Steve Pugh do.

Reclaiming Origins

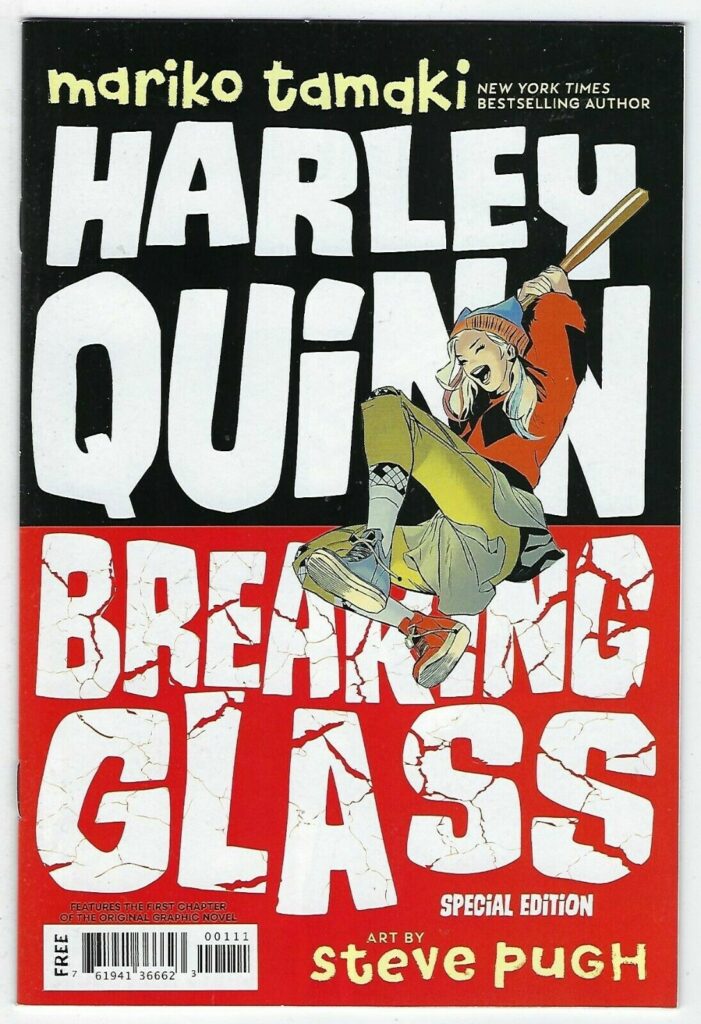

According to Coody, ‘mainstream comics allow for and even encourage multiple origins, especially multiple retellings or “resellings” of an origin story’ (2020: 15). Re-establishing origins has the potential to create ‘entry points’ for new readers who may lack access to a particular character’s backstory, and to enable creators to develop new perspectives on familiar media. As Coody suggests, ‘[a] fresh voice can do wonders for an old character’ (2020: 16). However, as discussed above, few creators have taken full advantage of this aspect of comics in their Harley origins, often opting for adaptations of the same androcentric narrative instead. Starting with the cover, Tamaki and Pugh make it clear that while their Harley Quinn origin story incorporates elements of the character’s history, it also brings Harley to life in unique ways. The book’s cover is divided horizontally so that the top half is black, and the bottom half is red, evoking the playing card aesthetics of Harley’s first appearances. The letters are in a bold white font which also appears differently according to the horizontal divide with the words on top, ‘Harley Quinn,’ written in solid letters, while the words on bottom, ‘Breaking Glass,’ appear to be shattered. Harley herself appears on the upper-right side of the cover, in a pose that suggests she is mid-leap. She has a gleeful, open-mouthed expression and wears a red sweater with black diamonds, a knit hat in red and blue, sneakers (one red and one blue), and fishnet stockings underneath her ripped cargo pants. Over her head she raises a baseball bat, poised to strike (Figure 1). The visual composition of Harley includes elements that would be familiar to fans of past media; the red and black diamonds point towards Harley’s first appearances, while the red and blue allude to her redesigns in the New 52 series. Conversely, that she is leaping onto the words ‘Breaking Glass’ as if to further shatter them signals a purposeful departure from her previously established origins. After Dini published Mad Love as a comic, he then adapted it and added it back into BTAS. In their discussion of the conclusion of the episode (during which the Joker throws Harley through a high window), Cruz and Stoltzfus-Brown write ‘when her body breaks the window, the only noise heard is shattering glass’ (2020: 210). Pugh’s cover subverts the tradition of breaking glass that surrounded Harley as a victim of violence and may even be read as Harley actively and joyfully smashing that tradition to bits. The words ‘Breaking Glass’ also allude to other aspects of Harley’s story, including the destruction caused in Gotham, for good and for ill, by Harley and by others, as well as to Harley’s burgeoning feminist activism (i.e. breaking glass ceilings). This combination of the familiar and the new allows Pugh to appeal to established audiences while also reimagining Harley in ways that not only avoid the problematic trends outlined above, but that actively combat them. Pugh’s strategy thus aligns with one of Tamaki’s stated aims as a feminist writer: ‘I try to not just avoid but negate traditional narratives’ (Tamaki 2014). Tamaki’s success in achieving this goal is evident as soon as the story begins.

The first page of Breaking Glass, for example, features Harley looking directly at the reader and speaking to an unseen audience. It is clear that she is telling her own story. Having Harley narrate her origin has been common throughout her history, but what is new in this case is Harley’s age (she is a teenager), and where the story starts (her arrival in Gotham before her first day of high school). Readers soon learn that Gotham High is pretty much like all high schools and all the characters one might expect to find in the story are teenaged students just like Harley. In this way, Tamaki levels the playing field between Harley and her peers; no one is superpowered, there are no notorious heroes or villains dominating the story, and like teenagers everywhere, all of Tamaki’s characters are in a period of transition. This is an important step in telling a feminist Harley origin story because like Tamaki’s other books centred on girls who are coming of age, Breaking Glass readers are made to understand ‘that the lives of their protagonists are works in progress and many things, most importantly their futures, are unresolved and unforeseeable’ (Stanley 2017: 198). Another notable change involves how Harleen Quinzel comes to adopt the moniker and alter ego Harley Quinn. Distinct from past iterations, Tamaki’s narrative decouples craziness and criminality, and has nothing to do with heteronormative romance. Through flashbacks, we learn that Harleen has always been prone to violence and may be something of a pyromaniac; however, those facets of her personality do not inspire her to pursue a life of crime. Instead, she is criminalised by an unjust system that ignores the ways poverty has made her and her family subject to various forms of abuse. [2] In other words, she is not criminalised because she is ‘crazy,’ but rather because she is subject to systemic oppression. When Harley does meet the character who will come to be the Joker, a teenage white boy named John Kane, she hardly takes notice, describing him as one of the ‘kids who are obsessed with their phones and wear expensive T-shirts that smell like the mall’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 20). Even at the point that both Harleen and John are exploring their alter egos, it is clear that Harley finds him ridiculous. At one point, for instance, John tries to tell Harley that she is merely a plaything and that he is an enigma. She responds saying, ‘you’re an enema? Huh, John Kane is an enema. Who Knew? See ya in court, enema!’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 173). Tamaki lays the groundwork for an ongoing antagonism between Harley and the Joker, but it is rooted in Harley’s rejection of John Kane’s narcissistic, shallow endeavour to sow chaos, rather than in an unhealthy romantic obsession.

Gone too is the sexual objectification of Harley in both her appearance and her relationships. As a teenager in a setting visually reminiscent of the contemporary US, Harley is styled in jeans, sneakers, an oversized fluffy sweater with two-toned squares, characteristic pig tails, and a knit hat formed into two horns or ears. Although she changes her outfits throughout the book, all of them are similarly evocative of concurrent street fashion appropriate for a high school setting, visually indicating Harley’s own aesthetic ideals and eschewing those informed by a heteronormative male gaze. Harley’s investment in the ones she loves is not new (Hoyer 2017), however as discussed previously, historically, her relationships have been overdetermined by her sexualised subjugation to the Joker. The first chapter in Breaking Glass focuses on the relationships that will become foundational to Harley throughout the book and John Kane/the Joker barely makes an appearance. From the beginning, Harley’s narration is filled with her recollections of things her mother said, and her flashbacks all centre on memories involving this figure. Centring these relationships, rather than Harley’s interactions with John Kane/Joker, is indicative of another of Tamaki’s principles for creating feminist texts. She states that one of her goals is ‘writing out and looking at the relationships between women, between mothers and daughters and friends’ (2014). In a charming twist on this aim, Tamaki establishes the first of Harley’s new relationships with ‘Mama,’ the gay man who inherited Harley’s deceased grandmother’s apartment, and who Harley describes as her ‘Fairy Godperson’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 12). Shortly thereafter, Harley meets and befriends Ivy, telling the audience that ‘from the moment Harleen met Ivy…she knew Ivy was a super-special person’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 23). The chapter concludes with Harley curled up on Mama’s couch with the queer men who work as drag queens at Mama’s club, and who become Harley’s found family. Establishing these connections makes Harleen ‘happy as a kitten on a radiator,’ giving her the feeling that ‘she had everything she needed’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 29). Through her relationships, Tamaki and Pugh make Harley more human and more relatable as a teenage girl. These bonds of love and friendship are also devoid of the misogynistic violence that framed Harley’s relationships in previous comics, strengthening the possibility of reading her as a feminist character. That Tamaki and Pugh choose to make most of Harley’s relationships in Breaking Glass queer (i.e., they defy patriarchal ideals of family or romance) is similarly important because it further distinguishes their origin story from its predecessors, and it productively disrupts the homogeneity of the superhero genre.

Queering Quinn

Scholars Darieck Scott and Ramzi Fawaz assert that ‘there’s something queer about comics’ (2018: 197). Even when one considers the tendency for mainstream superhero comics to proliferate heteronormative, patriarchal, racist, nationalist ideologies, there is no denying that ‘at every moment in their cultural history comic books have been linked to queerness or to broader questions of sexuality and sexual identity in US society’ (Scott & Fawaz 2018: 198). Scott and Fawaz also refer to the medium’s capacity to depict fantastical figures, worlds, and scenarios which has led to ‘a vast array of nonnormative expressions of gender and sexuality’ (2018: 201). Mel Gibson echoes Scott and Fawaz with specific reference to representations of girlhood: ‘comics are able to present a queer space in which cohesive and diverse groups exist that are not dominated by representations of white, affluent, able-bodied, Western heteronormative girlhood’ (2020: 2). Reflecting on this scholarship alone, it is possible to argue that Breaking Glass, a book written by a queer woman of colour that centres on a ‘deviant’ teen girl, and that has a diverse cast of characters, is by its very nature a queer text. However, in exploring specific aspects of the book—such as Harley’s eclectic narrative style, the incorporation of drag culture, and the absence of heteronormative romance—I suggest that this iteration of Harley’s origin is not only queer, but also decidedly feminist.

Harley begins her narration with the familiar phrase ‘once upon a time,’ signalling to her audience that her chosen mode of storytelling is fairytales. Initially, this choice may seem surprising since feminist scholars have demonstrated how western fairytales were historically intended to reinforce patriarchal gender norms and convey ‘appropriate’ social dynamics for children (Bottigheimer 1989; Warner 1994; Zipes 2006). It becomes almost immediately apparent that Harley’s version of a fairytale is deeply subversive of such norms. Reflecting on Little Red Riding Hood’s predicament, for instance, Harley says that she ‘would have just punched the wolf in the face. No lumberjack required’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 11). Her story also jumps from one genre to another, haphazardly mixing fairy tales with eschatological musings about angels, devils, and her personal addition, boogers. This framework of good and evil is harder for Harley to dismiss or rewrite, given her own history with the criminal justice system and the ongoing hardships her found family face. Allowing Harley to struggle with this kind of dichotomy, rather than committing to it, powerfully disrupts conventions of the superhero genre. Scholars David A. Pizarro and Roy Baumesiter argue, ‘in tales of superhero versus supervillain, moral good and moral bad are always the actions of easily identifiable moral agents with unambiguous intentions and actions’ (2013: 20). Although this is somewhat reductive of the genre, it does reflect normative assumptions about the seamless alignment of good and evil with hero and villain—or in Harley’s case, angel and devil. Of course, this kind of clear-cut distinction is rarely possible to make in real life, and because Harley’s circumstances are meant to resemble our own, she is infinitely more relatable precisely because she struggles to understand herself in these terms.

Near the conclusion of Breaking Glass, Harley is in prison after being framed by John Kane/Joker for blowing up part of a building. Four horizontal panels illustrate her day-to-day activities, the bottom of which shows her sitting at a desk writing a letter. Cascading down the page, from top to bottom, are caption boxes showing the contents of her letter:

Hello, Mama. Prison is not as fun as drag. I have spent a lot of time thinking… …’bout what my mom said about there being two kinds of people. I think it is more complicated than that. I think people can be a lot of things. Things you don’t expect. I don’t get all of it but I feel like I get a little more than I did a month ago. I thought I could spot a booger from fifty yards away. I was wrong. Now I know there are Jokers. There are people who will do anything to get what they want. My mom believes in angels… I don’t know if I do. I might not know what I am but I know what I have to do. And, Mama, if you ever need one… …I will be your angel.[3] (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 188-89)

According to Stanley the strikethrough text is a technique common in Tamaki’s graphic novels focused on teen girls. It generates a level of ambiguity ‘that show[s] key characters changing their minds and struggling to understand, [serving] to remind readers of the intensity of change and the uncertainty of perception in adolescent life’ (2017: 204). This is heightened by Pugh’s art which, throughout much of the book, employs shades of only two or three colours, a choice believed to draw a greater focus on the ideas and thought processes being communicated (Duncan and Smith 2009: 142). Thus, Harley’s questioning does not arise because she is unambiguously morally bad, but simply because she is a teenager.

Harley’s (seeming) disbelief in the kinds of angels her mother ascribes to also disrupts the heteronormative expectations established in previous iterations of her origin story. In Mad Love, Batman contemplates the relationship between the Joker and Harley Quinn, implying that they are appropriate ‘playmates’ because ‘Harley Quinn was no angel’ (Dini & Timm 1994). Through a series of flashback scenes, it becomes clear that Batman is referring to Harley’s use of sex to get good grades in graduate school. As Michelle Vyoleta Romero Gallardo and Nelson Arteaga Botello argue, Batman’s judgement relies on an understanding of ‘angels as spirits of pureness. Within this framework, to say that a woman does not have the characteristics of an angel is to negate her purity, a purity that manifests itself in attributes such as goodness and morality.’ These attributes, they note, are tied to ‘the negation of the [female] body and the evasion of sexuality’ (2017). Harley’s observation in Breaking Glass that people are more complicated than being unambiguously good or bad, and the doubt she shows about angels (as beings of purity) call into question Batman’s system of values. From the perspective of Tamaki’s Harley, it is both irrelevant (since her origins diverge from those in Mad Love) and untenable in light of what she has learned about fighting for justice in an unjust world. Instead, Harley suggests that if she is any kind of angel, she is the type that will do whatever it takes to protect and fight for those she loves, and in the case of Breaking Glass, her love extends to her queer family and friends.

Harley’s chaotic narrative style also transgresses the gendered norms of the superhero genre because it facilitates a look at her all-female audience. The first page of the last chapter shows Harley and two guards from the back as she is escorted into prison with a caption box in the bottom right corner reading ‘The End,’ indicating the conclusion of the story. When one turns the page, readers become visually aware that they are no longer listening to Harley narrate the past, but that they have joined her in her present moment in prison, asking her audience what they believe is the ‘morale’ of the story. The young women ask questions and make comments that align with the mishmash of metaphors and traditions shown in the previous pages: ‘Wait. Is this still a Red Riding Hood thing?’ and ‘Yeah, I feel like your story has a lot of unresolved literary allusions’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 176). Despite the superhero genre’s history of catering to a presumed white male audience (Hanley 2018: 222), Tamaki and Pugh show Harley relaying her origin story to a group of fascinated, if also confused, young women of varying ethnicities. Because the girls’ questions suggest that we as readers heard what they heard, it is possible to assume that this version of Harley’s origin story is specifically intended to appeal to a female audience—or at least, we are getting a version that Harley, as a teen girl, believes will appeal to her interlocutors.

‘The drag show must go on’

Harley’s letter to Mama also hints at the ways that women and drag culture are foundational to her burgeoning sense of self and her growing awareness of the complexity of life. Whereas previous iterations of her origins have suggested that Harley’s adoption of carnivalesque clown aesthetics was done in the image of the Joker, Breaking Glass rewrites the matrilineal roots of these choices. When Harley first arrives in Gotham, she makes her way to her grandmother’s apartment where she has been sent to live while her mother takes work on a cruise ship. Upon entering the apartment, Harley discovers clown statuettes and paintings dominating the décor. Mama explains to Harley that her grandmother (now deceased, unbeknownst to either Harley or her mother) was ‘a bit of a clown fanatic’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 13). In Harley’s first flashback to her tenth birthday, indicated by Pugh’s use of sepia tones, she has been taken to Bingo Betty’s Bonkers Arcade by her mother. Harley wears a bi-coloured jester’s hat and cradles an impish looking doll; items she is likely to have won inside, judging by a sign reading ‘pizza, games, prizes’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 16). Ivy also plays a role in deepening Harley’s love of clown fashion and helps her to find another layer of meaning in the garb. One day at school, Ivy and Harley stumble on a poster for the Film Club, and as Ivy begins to explain that the club has never shown a film directed by a woman, the club president, John Kane, dismisses the critique as a pointless, ‘tired diversity agenda’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 32). In response, the girls protest the next meeting of the club dressed as clowns, drawing attention to the absurdity and foolishness of the club’s sexist standards. Ivy explains to Harley that the outfits are also a tribute to the Guerilla Girls, the masked feminist activists who raise awareness about the exclusion of women in art. All these visual and narrative choices reframe Harley’s aesthetic as arising from the influence of the women in her life in a performative or iterative process. The moment she steps into the role of ‘Harley Quinn’ is built on these experiences while also relying on her inclusion into drag culture.

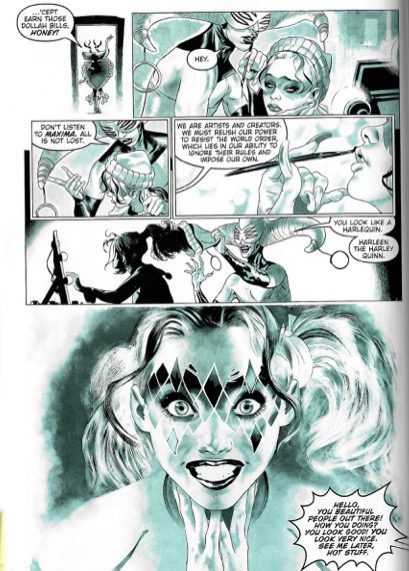

One night at Mama’s drag club, Harley sits backstage receiving a makeover from Hello Dali (a.k.a. Daniel), the person to whom Harley is closest aside from Mama. As the queens discuss their worries about the gentrification of the neighbourhood and the threat it poses to the club, Dali paints Harley’s face and insists that she not despair: ‘We are artists and creators. We must relish our power to resist the world order, which lies in our ability to ignore their rules and impose our own.’ Once Harley’s face is finished, Dali pulls her knit hat off her head and proclaims ‘You look like a harlequin. Harleen the Harley Quinn.’ Harley leans towards the mirror and in the bottom panel of the page, the reader sees what Harley sees, a reflection of herself, her eyes wide with delight and surprise at the harlequin diamond mask painted across her face (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 44) (Figure 2). The importance of this page cannot be overstated. Like previous versions of the character, the removal of Harley’s hat in this instance signals a shift away from her goofiness and naiveté (Wigard 2017). Because she is shown with the hat on in her childhood, or while at high school (a place she does not take seriously), the appearance of Harley’s hair visually confirms a process of transformation. Crucially, Dali (someone to whom Harley is bonded in queer kinship) names her ‘Harleen the Harley Quinn’ in a manner similar to how he and the other drag queens adapted their own given names to stage names. Just as Tamaki and Pugh make use of the drag queens’ given names and stage names, so too are both Harleen and Harley used throughout the book, abandoning the troubling duality in previous origin stories in favour of queer fluidity. Dali also links the makeup and moniker to resistance. As Judith Butler suggests, drag or ‘parodic repetitions’ have the potential to be disruptive or subversive of hegemony, particularly mechanisms of gender normativity (1990: 187-88). [4] Combined, Dali’s guidance queers Harley’s discovery of self and establishes the potential for ‘Harley Quinn’ to be read as a kind of liberatory drag. [5]

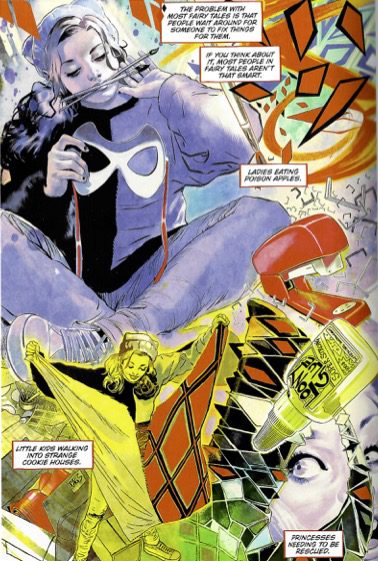

This potential is developed further by the construction of Harley’s final costume. In pursuit of ‘some butt and mascara’ for his own costume, Dali invites Harley ‘to the temple of all that is good and costs a dollar,’ the local dollar store (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 98-99). While there, Harley buys a mask that will become integral to her costume and that Dali describes as ‘Paris is Burning, o-per-a realness’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 101). This scene points to the ways real queer subjects, such as drag queens, use crafting as a means of worldmaking. As Daniel Fountain points out, the use of craft may be ‘viewed as a process, as in crafting an identity, or crafting a community’ (2021). Moreover, Dali’s reference to Paris is Burning, the 1990 documentary about New York City’s ball culture, alludes to the ways in which queer crafting draws ‘inspiration from a range of sources’ and ‘demonstrates the ways in which queer subjectivities are often formed out of an eclectic array of (sub)cultural references and reworkings of dominant cultural representations’ (Fountain 2021). Fountain’s point becomes even clearer in reference to the rest of Harley’s costume. Following her trip to the dollar store, Harley meets with the person calling themselves the Joker (although she does not yet know who he is). In her desperation to help her friends and family fight their eviction from the neighbourhood because of gentrification, Harley accepts the Joker’s offer to join his plot to take down Kane Enterprises, the corporation driving the gentrification. However, rather than donning the costume he gives her—a skimpy cheerleader uniform akin to a bra and panty set—Harley makes her own. In doing so, Harley enacts an explicit rejection of the heteronormative sexist stylings of her character’s past. Pugh creates a full-page panel in the style of a collage, with Harley drawn in several different postures, indicating the different tasks involved in her creative process. It is one of the most colourful pages in the book, making use of all the colours in the rainbow, and so, emblematic of the queer community. Harlequin diamonds and art supplies float along the right side of the page as Harley plans, paints, rummages, and rips her costume into being on the left (Figure 3). The finished product renders the aesthetics of her previous iterations through the lens of drag. She wears her dollar store mask, now painted in black and white diamonds, a red, black, and white jester collar, a body suit in a large red and black harlequin pattern, and a faux fur black and red bolero. Armed with Mama’s baseball bat—kept in case of ‘bad company’—Harley Quinn sets off into the night to save her neighbourhood (however misguided this might be). Harley’s new identity is inspired by her relationships with women, crafted within her queer community, and emboldens her to fight for what she believes is right in ways that negate the misogyny in her character’s past.

One final point to be discussed in terms of how Breaking Glass may be read as a queer feminist text is its omission of heteronormative romance. As mentioned previously, the antagonism that manifests between John Kane/Joker and Harley is devoid of any erotic or romantic feeling. Harley’s interactions with John at school lead her to conclude that he looks ‘like an ad for a blazer,’ he is ‘like a human necktie,’ and ‘a person a lot of people thought about decking’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 32-33). It is clear at several points throughout the book that Harley is more fascinated by the Joker, however she also complains that he talks too much and upon discovering his true identity, she concludes that ‘he’s a mega-asshole’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 165). If Harley does have any romantic feelings, they are most probably for Ivy. Although DC officially declared that Harley and Ivy were involved in a romantic and sexual relationship in 2015, Tamaki and Pugh do not follow suit (Owens 2017). Unlike previous media that relied on subtext to simultaneously suggest a queer relationship and maintain a heteronormative status quo (Liddell 2017), Breaking Glass is ambiguous about Harley and Ivy’s relationship because of their status as teen girls. Stanley clarifies that ‘[w]hen it comes to the subject of developing desire and sexuality’ in her coming-of-age books, Tamaki often ‘[deploys] characteristic complexity and thought-provoking ambiguity’ because that is what is appropriate for teen characters who are ‘in the midst of adolescent discovery’ (Stanley 2017: 196-202). Thus, while there are several panels where Harley and Ivy exchange what could be looks of attraction and longing, that aspect of their relationship is left unresolved. Although this may seem unsatisfying to readers interested in seeing more queer romance in comics, it nevertheless disrupts the heteronormativity of Harley’s early history and the superhero genre.

‘You want change… you have to be change’

The relationship between Ivy and Harley is crucial in another way—how it helps Harley, and by extension her readers, to engage with issues of race, racism, and ‘the ways in which race intersects with other ideas of difference’ (Stanley 2017: 193). Comics scholar Lillian Robinson argues that although many contemporary superhero comics have increased the numbers of powerful women in their pages, they have generally done so in a way that ignores ongoing, real-world gender inequity, racism, and heteronormativity, making them postfeminist at best. For Robinson, representations of feminism in comics must not only depict ‘a “present time” where gender equality flourishes and where accusations of discrimination are baseless,’ they also need to show ‘us how such conditions came to pass’ (2004: 138). Relatedly, many scholars of race have expressed skepticism of the tendency for mainstream comics to cast mixed-race characters or characters of colour as a way to ‘diversify’ their titles without also demonstrating the specific challenges such characters would face. Sharon Change, for instance, writes ‘painting mixedness as a super power able to undo racial strife turns out to be a shallow form of multiculturalism that avoids the real, continued, and deep oppressions people of colour face all over the world’ (2015: 190). Throughout Breaking Glass, readers are made to understand how interlocking, co-constitutive structures of inequality inform life in Gotham City, [6] and how acknowledging and resisting those systems are an integral party of Harley’s coming-of-age journey

Central to the book’s ability to meaningfully engage with intersectional injustice is its diverse cast of characters and the detail in which Tamaki and Pugh depict their lives. The conflict that they all face is the gentrification of their neighbourhood by Millennium Enterprises owned by the Kanes, the primary villains of the story. Like the young man who stole Harley’s family van, the Kanes are wealthy white people. Interweaving villainy, wealth, and whiteness may be read as visual shorthand for the harm caused by the intersection of capitalism and white supremacy. The fact that Harley’s found family are queer drag queens, and that Ivy and her parents are a Black and Asian-American biracial family, echo the real demographics of people who have been harmed most by gentrification. Once it becomes apparent that Mama and his family will be evicted, Mama laments that he has been in the building for twenty years. Dali also explains to Harley that Mama has already lost so much, alluding to the AIDS epidemic. One can conclude that Mama’s situation recalls ‘the process of intense gentrification that New York faced during the years 1981 to 1996, when the AIDS epidemic swept through the City’ (Fountain 2021). Similarly, Ivy’s family’s community involvement resembles the efforts of activists like Majora Carter whose initiative ‘Greening the Ghetto’ sought to reverse the environmentally and socially harmful conditions created by redlining in the Bronx (Prigg 2013). Collectively, this cast makes clear who has the most to lose in social systems that mirror our own.

Harley also witnesses the kinds of discrimination these characters face on a more individual level. For example, when Dali and Harley are out for ice cream following their dollar store shopping spree, another wealthy white woman—recognisable because of the sweater vests and ties her children wear, implying they are enrolled in private school—interrupts, claiming that Dali’s behaviour is inappropriate for a family establishment. Because of Dali’s long hair, proclamations about being ‘fierce,’ and voguing, the woman’s complaint is framed as homophobic. Dali confirms this later with his imitation of the woman, ‘You can’t be gay while my kids are eating ice cream!’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 104). At Gotham High, Ivy and Harley are called into the principal’s office following one of their protests of the Film Club. The principal uses titles and last names to refer to Harley and John Kane but uses Ivy’s first name following ‘Miss.’ Ivy calmly requests that the principal refer to her in the same way he has referred to the other students, to which he responds ‘Miss Ivy, as a student at this school, I will ask you to speak to me in a tone that is respectful’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 123). Once in detention, Ivy explains to Harley why calling her ‘Miss Ivy’ was racist: ‘Like I was some housemaid from the ‘50’s or something’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 125). Although these scenes emphasise homophobia in one instance, and racism in the other, it is important to note that Dali is a person of colour and Ivy is a teen girl. It is not possible to claim that Dali only experiences homophobia or that Ivy is discriminated against solely because of her race, thus confirming the intersection of systems of oppression. However, helping readers to see how inequitable social structures overlap and co-construct one another is only part of the work a feminist text should do. As Robinson argues, feminist comics must also demonstrate how justice is achieved under such circumstances.

Despite Harley’s propensity to solve problems with violence, Breaking Glass highlights the many constructive ways the marginalised citizens of Gotham work towards equity and justice. For instance, even though Harley and Ivy’s first protest does not induce the Film Club to change, their efforts are not in vain; other students are inspired by their efforts and ask to take part in future demonstrations (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 108). This points towards the real power of protests to draw attention to a cause and to mobilise a group. By the end of the book, Ivy tells Harley that she has decided to run for Film Club president because if John Kane won’t allow the club to adapt, she will challenge his right to make that determination (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 181). Ivy’s persistence and willingness to change her strategy demonstrates for young readers that achieving a desired outcome requires ongoing effort and adaptation. The actions of Ivy’s parents as a city councillor and a community garden manager also place an emphasis on the importance of grassroots movements. Working for change at a local governmental level or creating a space that directly contributes to peoples’ well-being are modes of action that more immediately address the needs of the people in a given community. Their organisation of a march in protest of the neighbourhood-wide eviction similarly draws attention to the importance of communal action, and again, represents one way in which real citizens can work towards justice for their communities. Organising or participating in marches may not actually stop problems like evictions, but these actions can help solidify coalitions, increase awareness of injustice, and signal to authorities that people will not tolerate further abuses. Finally, as mentioned above, drag may also function to disrupt oppressive systems. While performing drag may not be available to everyone that reads Breaking Glass, making art, crafting, and being fabulous are open to all, and as Mama writes in his letter to Harley, ‘the world needs more of that right now’ (Tamaki, Pugh, & Mangual 2019: 183). Harley’s own contributions to Gotham’s fight for justice are a bit more fraught, but the mistakes she makes are arguably as educational for young readers as the models of activism just described.

Harley’s (mis)understanding of the need for structural justice is most evident in her interactions with Ivy. The dialogue around the girls’ clown protests reveals that Harley conceives of them more as a chance to dress up than an attempt to effect change. Ivy’s repeated reminders to Harley that these protests should be about calling attention to discrimination underscore Harley’s lack of genuine interest in the problem. Her willingness to dress the part, while remaining oblivious to its meaning recalls Butler’s warning that parodic performances are not inherently transgressive and run the risk of leaving the status quo intact (Butler 1990: 189). Harley also fails to stand up for Ivy in the principal’s office and reacts with shock when Ivy calls her out. Harley claims she did not know the principal was being racist or that she should step in. An earlier scene in the community garden in which Harley must explicitly admit her ignorance of social history makes her claims plausible and suggests that she may not have understood her responsibility. However, I propose that these scenes show Harley exhibiting what Koa Beck has identified as ‘white feminism,’ a state of mind that privileges personal autonomy, fails to question power structures, and exhibits a deliberate lack of racial literacy (2021). This is visually substantiated by the knit hat Harley wears which resembles the ‘pussy hats’ women wore to marches protesting the election of Donald Trump, and which became emblematic of ‘white feminists’ who tended to be uninterested in social justice that required ongoing effort and self-reflection. As I have noted, Harley does eventually stop wearing the hat, and just as that signifies a shift away from her goofiness, it may also indicate her growing awareness of her own ignorance, and more importantly, her responsibility to address it. For young readers who are similarly uneducated about social issues, Harley’s mistakes, and her willingness to admit them, may make feminist praxis more accessible. Further, watching Harley get it wrong may be instructive of what to do differently. In opposition to Harley, readers might learn to reflect on the limits of certain methods of activism, bear witness to injustice, speak truth to power, and commit to learning. Ultimately, Tamaki and Pugh make use of Harley’s journey to show that even when one’s efforts to make positive change are imperfect, humility, self-reflection, and commitment to do better are what matters, with or without a superhero suit.

Through their reclamation of origin stories, Tamaki and Pugh achieve something few other creators have: a feminist Harley Quinn superhero comic. Reimagining Harley as a teenage girl allows Tamaki and Pugh to style her in ways that avoid the sexualization embedded in Harley’s character history. By queering storytelling conventions, they enable Harley to push back against patriarchal ideals of feminine passivity, silence, and purity. Their choice to eschew heteronormative romance, develop bonds between Harley and queer characters, and infuse Harley’s antihero identity with drag culture, also allow Tamaki and Pugh to tell a more inclusive story that negates the misogyny of many earlier iterations. Finally, by reimagining Gotham in ways that more closely resemble the contemporary US, Tamaki and Pugh show the characters of Breaking Glass engaged in a fight for justice that is recognisable and replicable by readers. In short, Tamaki’s method of feminist writing and Pugh’s expressive art ensure Harley Quinn a more feminist future by reclaiming and reforging her past.

Notes

[1] In line with the ways Tamaki describes her methods of feminist writing (2014), I am working with Estelle Freedman’s definition of feminism: ‘a belief that women and men are inherently of equal worth. Because most societies privilege men as a group, social movements are necessary to achieve equality between women and men, with the understanding that gender always intersects with other social hierarchies’ (2003: 22). Therefore, in claiming that Breaking Glass is a feminist text, I argue that the book demonstrates a commitment to the ‘belief that women and men are inherently of equal worth,’ and includes representations of collective action aimed at achieving intersectional justice.

[2] For example, Harley’s first flashback shows her family’s van being stolen. When Harley hunts down the perpetrator we learn that he is a wealthy teenage white boy who steals cars for fun. Harley decides to ‘take out a well-deserved poundin’’ on ‘Reggie’ whose mother then calls the police (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 48). We learn through a subsequent flashback that Harley is arrested, booked, and sent to court; Reggie’s father uses his connections to get Harley’s mother fired from her job, and Reggie is unpunished, ‘skippy-dipping around like it’s his birthday’ (Tamaki, Pugh & Mangual 2019: 79).

[3] Strikethrough text occurs in the text of the comic.

[4] Butler is careful to note that drag or parody are not always subversive, some performances may be ‘domesticated and recirculated as instruments of cultural hegemony’ (1990: 189). This kind of risk is indeed one Harley is made to confront, a point to which I will return in the next section.

[5] It is possible to assume that Harley also sees her antiheroine identity as a form of drag. While the first line of the letter, ‘prison is not as fun as drag,’ is certainly a reference to her found family and Mama’s club, the fact that Harley was arrested while donning her queerly crafted ‘Harley Quinn’ costume suggests that she may also be referring to her own performance.

[6] One way Tamaki and Pugh achieve this depiction of Gotham which I do not discuss in detail is via the many statements Ivy makes about their city, which are so explicitly critical of systemic oppression they do not warrant further analysis. See, for example Tamaki et. al. 2019: 41, 92 & 180-181.

REFERENCES

Andersen, Brian (2019), ‘When Harley Quinn Met Her Drag Family.’ The Advocate, 16 July 2019, https://www.advocate.com/art/2019/7/16/when-harley-quinn-met-her-drag-family (last accessed 21 March 2023).

Beck, Koa (2021), White Feminism: From the Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind, Atria Books.

Bottigheimer, Ruth (1989), Grimms’ Bad Girls and Bold Boys: The Moral and Social Visions of the Tales, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Butler, Judith (1990), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York; London: Routledge.

Chang, Sharon (2015), Raising Mixed Race: Multiracial Asian Children in a Post-Racial World, New York; London: Routledge.

Conner, Amanda, Jimmy Palmiotti & Stephane Roux (2014), Secret Origins, No. 4: Harley Quinn, New York: DC Comics.

Coody, Elizabeth Rae (2020), ‘Rewriting to Control: How the Origins of Harley Quinn, Wonder Woman, and Mary Magdalene Matter to Women’s Perceived Power’, in Monstrous Women in Comics, Samantha Langsdale & Elizabeth Rae Coody (eds), pp.15-30, University Press of Mississippi.

Cruz, Joe & Lars Stolfus-Brown (2020), ‘Harley Quinn, Villain, Vixen, Victim: Exploring Her Origins in Batman: The Animated Series’, in The Supervillain Reader, Robert Moses Peaslee & Robert Weiner (eds), pp. 203-13, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Dini, Paul, Yvel Guichet & Aaron Sowd (1999), Batman: Harley Quinn, New York: DC Comics.

Dini, Paul & Bruce Timm (1994), The Batman Adventures: Mad Love, No. 1, New York: DC Comics.

Duncan, Randy & Matthew J. Smith (2009), The Power of Comics: History, Form & Culture, New York & London: Bloomsbury..

Fountain, Daniel (2021), ‘Survival of the Knittest: Craft and Queer-Feminist Worldmaking.’ MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture 8, https://maifeminism.com/survival-of-the-knittest-craft-and-queer-feminist-worldmaking/. (last accessed 21 March 2021).

Freedman, Estelle (2003), No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women, New York: Ballantine Books.

Gibson, Mel (2020), ‘Queer Girlhoods in Contemporary Comics: Disrupting Normative Notions.’ Girlhood Studies, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 1-16.

Glass, Adam, Clayton Henry & Ig Guara (2012), Suicide Squad 4, No. 7, New York: DC Comics.

Hanley, Tim (2018), ‘The Evolution of Female Readership: Letter Columns in Superhero Comics’, in Gender and the Superhero Narrative, Michael Goodrum, Tara Prescott & Philip Smith (eds), pp. 221-51, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Hoyer, Amanda (2017), ‘Victim, Villain or Antihero: Relationships and Personal Identity’, in The Ascendance of Harley Quinn: Essays on DC’s Enigmatic Villain, Shelley Barba & Joy Perrin (eds) Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Jackson, Cia (2017), ‘Harlequin Romance: The Power of Parody and Subversion’, in The Ascendance of Harley Quinn: Essays on DC’s Enigmatic Villain, Shelley Barba & Joy Perrin (eds) Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Liddell, Alex (2017), ‘Duality and Double Entendres: Bi-Coding the Queen Clown of Crime from Subtext to Canon’, in The Ascendance of Harley Quinn: Essays on DC’s Enigmatic Villain, Shelley Barba & Joy Perrin (eds) Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Owens, Emilee (2017), ‘”It Is to Laugh’: The History of Harley Quinn”’, in The Ascendance of Harley Quinn: Essays on DC’s Enigmatic Villain, Shelley Barba & Joy Perrin (eds), Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Pizarro, David & Roy Baumesiter (2013), ‘Superhero Comics as Moral Pornography’, in Our Superheroes, Ourselves, Robin Rosenberg (ed.), pp.19-36, New York: Oxford University Press.

Prigg, Tom (2013), ‘Urban Activist Majora Carter Promotes ‘“Greening the Ghetto”’, The Allegheny Front, 19 April 2013. http://archive.alleghenyfront.org/story/urban-activist-majora-carter-promotes-greening-ghetto.html (last accessed 21 March 2023).

Robinson, Lillian (2004), Wonder Women: Feminisms and Superheroes, New York; London: Routledge.

Roddy, Kate (2011), ‘Masochist or Machiavel? Reading Harley Quinn in Canon and Fanon.’ Transformative Works and Cultures 8.

Romero Gallardo, Michelle Vyoleta & Nelson Arteaga Botello (2017), ‘There Shall Be Order from Chaos: Hope and Agency Through the Harlequin’s Subalternity’, in The Ascendance of Harley Quinn: Essays on DC’s Enigmatic Villain, Shelley Barba & Joy Perrin (eds), Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Scott, Darieck & Ramzi Fawaz (2018), ‘Introduction: Queer about Comics’, American Literature Vol. 90, No. 2, pp.197-219.

Stanley, Marni (2017), ‘Unbalanced on the Brink: Adolescent Girls and the Discovery of the Self in Skim and This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki’, in Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Collection of Critical Essays, Michelle Anne Abate & Gwen Athene Tarbox (eds), pp.191-204, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey