Gender-Bender Manga: Performance, Perception & Narratives of Subversion

by: Margaret Mertz , March 30, 2023

by: Margaret Mertz , March 30, 2023

Introduction

Gender-bending in storytelling is not a new phenomenon. Stories in which characters perform as, or physically transform into, another gender have existed worldwide since antiquity, appearing in everything from Greek and Hindu mythology and Russian and Egyptian folklore to Shakespearean and Thai theatre and Italian and Chinese opera. Though a handful of stories with these themes appear in contemporary Western media, gender-bender narratives are significantly more prevalent in manga, reaching massive popularity with both Japanese and international audiences. While many elements of Japanese popular culture—from mecha robots to kawaii art styles—have permeated Western media in recent decades, this sizeable, fascinating, and gender-expansive sub-genre has remained predominantly in Japanese media.

Japan has a long and complex history of entertainment that plays with gender, most famously the female impersonating roles in all-male Kabuki theatre, the onnagata (女形), and the male impersonating roles in the all-female Takarazuka Revue theatre, the otokoyaku (男役). [1] Indeed, the manga industry itself has its history tied to gender-bending, with many of the elements associated with the medium today—big eyes, androgynous figures, and long-form narratives—originally appearing in Osamu Tezuka’s 1953-1956 manga Ribon no Kishi (Princess Knight), where a princess is accidentally born with the heart of both a boy and a girl, and as such is able to disguise herself as a boy to ascend the throne (Fujimoto: 2004). Though scholars have analysed many of the androgynous and non-normative gender characterisations in manga, these analyses have primarily linked gender-bending to exclusively female desire. By focusing solely on an assumed female audience, these readings limit not only the scope of this sub-genre of manga, but its subversive potential.

Though gender-bender manga are often written and drawn by female-identifying mangaka (manga artists), these narratives and elements can be found throughout the medium’s four main demographics—shōnen, shōjo, seinen, and josei—regardless of the intended audience’s age and gender. [2] While the narratives are diverse, a decade of reading gender-bender manga has led me to identify three categories across the subgenre—intentional, incidental, and involuntary—that I will expand upon below. By exploring these works in relation to Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble and Undoing Gender, I will demonstrate how gender-bender manga—ranging from shōnen martial-arts fantasies (Ranma ½), to shōjo harem romances (Ōran Kōkō Hosuto Kurabu), to josei slice-of-life comedies— (Kuragehime)—directly engage with, if not outright critique, the flimsy, restrictive, and ill-fitting construction of our modern gender binary.

Through analysing the fluid characterisation and contrasting embodiments of femininity in Akiko Higashimura’s Kuragehime, I will explore how intentional gender-bender manga narratives exemplify Butler’s theorised link between the performance of gender and physical space. I will then briefly touch upon the other two narrative categories—incidental with Ouran and involuntary with Ranma ½—to demonstrate how gender-bender manga uses a combination of embodied performance, physical space, external perception, and social positioning to deconstruct the essentialism of the gender binary. In doing so, this Japanese sub-genre shares a subversive feminist discourse with a broader audience, a discourse that is perhaps too subversive to be profitably regurgitated by contemporary Western culture.

First, though, a couple of points of clarification: When I say a gender-bender narrative is intentional, I mean that the gender-bending in question is the result of deliberate choices made by the characters regarding their appearance, language, and behavior, with the aim of being perceived as a gender distinct from the one they were assigned at birth. These manga speak to questions of self-identity: how we want to live our lives and why. Western audiences are most familiar with this category, as they often involve a character crossdressing to achieve some sort of goal—a narrative device that has existed for hundreds of years, ranging from Thor disguising himself as a bride in the Poetic Edda, to Shakespeare’s male-presenting heroines in Twelfth Night and As You Like It, to the cross-dressing soldier in Disney’s animated film Mulan, which itself was based on the 4th-6th century Chinese ballad of the same name. A few examples in manga include Hana No Kishi, Mint na Bokura, and Usotsuki Lily, though in this discussion, we will be exploring intentional narratives through Kuragehime, a manga in which one of the two protagonists, Kuranosuke Koibuchi, intentionally cross-dresses, not only because he likes female fashion, but because his performance will allow him to become friends with a group of women who have sworn off men.

Incidental narratives are a little harder to define, as they are stories in which a character is mistaken as representing a gender distinct from the one they were assigned at birth, and this initial moment of misgendering drives the story. Even if the crossdressing or gender transformation afterwards is purposeful, the initial moment is not sparked by an internal desire and identification, and is instead often reflective of a character’s androgyny, lack of adherence to gender stereotypes, and/or general nonchalance about gender. As such, these manga speak to how gender is largely perceived by others to fit their own ideas and desires, and they often fall into their own binary: feminine men mistaken as women and masculine women mistaken as men. The manga Ai Ore!, Aoharu x Kikanjuu, and Boku Girl are a few titles from this category; however, we will be focusing on Ōran Kōkō Hosuto Kurabu (Ouran High School Host Club, and henceforth referred to as Ouran) a manga about Haruhi Fujioka, a girl who is mistaken for a boy, and who, when her gender is discovered, responds, ‘Never claimed otherwise.’ (Vol. 1: 54)

Involuntary narratives come in many forms, from magic to cruelty to mischief, but they always involve external forces manipulating the characters regarding gender and sex. Sometimes these manipulations are merely nominal and language based, sometimes they are regulated through mandated clothing and behavioral changes, but they predominantly feature sudden, non-consensual body modification, in which the character physically transforms into the opposite sex. These manga speak to the expectations, anxieties, and lived experiences of gender, and often involve reflections on what it means to have a sexed body in society. A few titles include Kanojo ni Naru Hi, Shishunki Bitter Change, and Fukigen Cinderella. However, in this discussion we will be exploring involuntary narratives through Ranma ½ and its titular protagonist, a hyper-masculine teenage martial artist cursed to transform when doused with different temperatures of water: cold will turn him into a girl, hot will turn him back into a boy.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the forced category is also the one that has the widest range of sexual and fetishistic themes, with these stories often appearing in the seinen demographic. However, due to the length and relative scope of this paper, I will not be addressing these works, as the prevalence of irreversible transformations in sexually explicit narratives warrants much further discussion, especially regarding the possibility of rectifying fetishised oppression with meaningful feminist critique. On a similar note, I will not be discussing manga that explicitly addresses transgender experiences and/or has characters that explicitly identify as transgender (such as Wandering Son, Family Compo, or Our Dreams at Dusk) as these narratives also deserve further study. Though many characters in gender-bender manga are considered in fan-spaces to be transgender, and most of the characters discussed here could arguably be described from a Western and anglophone lens as gender fluid, genderqueer, or non-binary, I will not be using these terms to discuss them, partially because these terms were not widely used in Japan during the years and cultural contexts in which these manga were published, and partially because the characters do not refer to themselves in such terms. Therefore, in this analysis, I will be referring to the gender-bending characters by the pronouns that they predominantly use when referring to themselves.

Finally, throughout this paper I will be using the word performance to refer to the performed actions of a character; this is not to be confused with Butler’s theory of performativity, which, while foundational to the scholarship, is not directly relevant to this discussion but nonetheless echoes throughout this paper. For the sake of clarification, and to drastically oversimplify, to say that gender is performative means it creates a series of effects, giving meaning to the acts that it names by referencing the acts that have already named it, and thus giving the impression that this relationship is natural and necessary. Performance, on the other hand, refers to the actions, gestures, aesthetic choices, manners of speaking, etc., embodied in exterior space that give an impression of a natural and abiding gender. In short, performativity is the consolidation, the impression, the way this performance—created for and filtered through society—is internalised and essentialised.

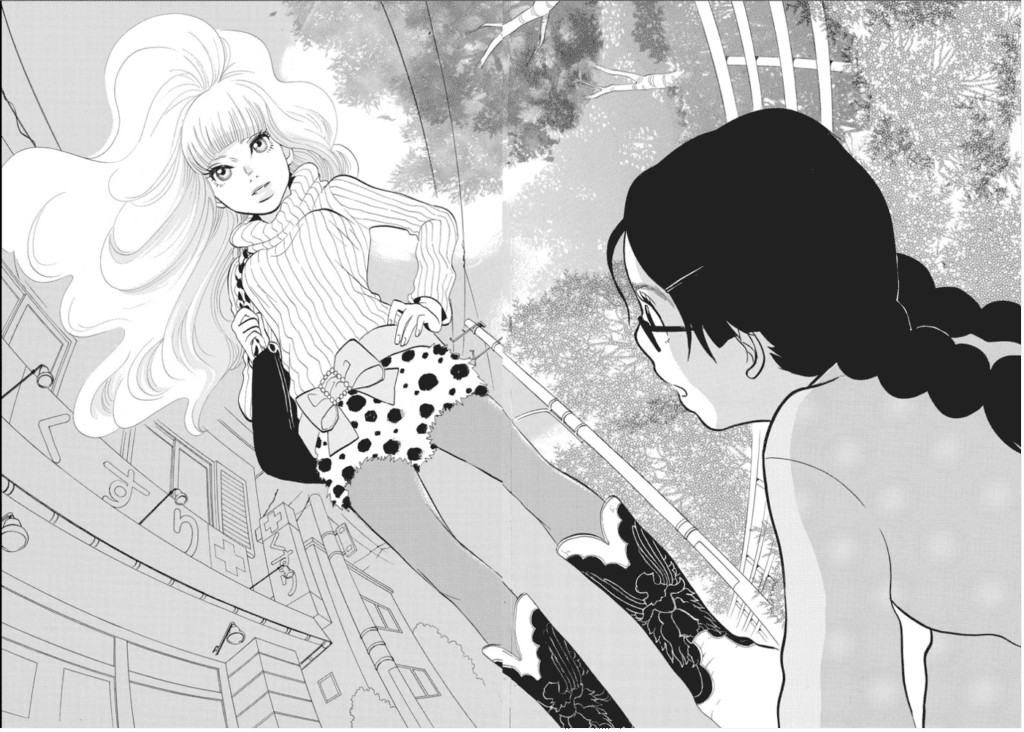

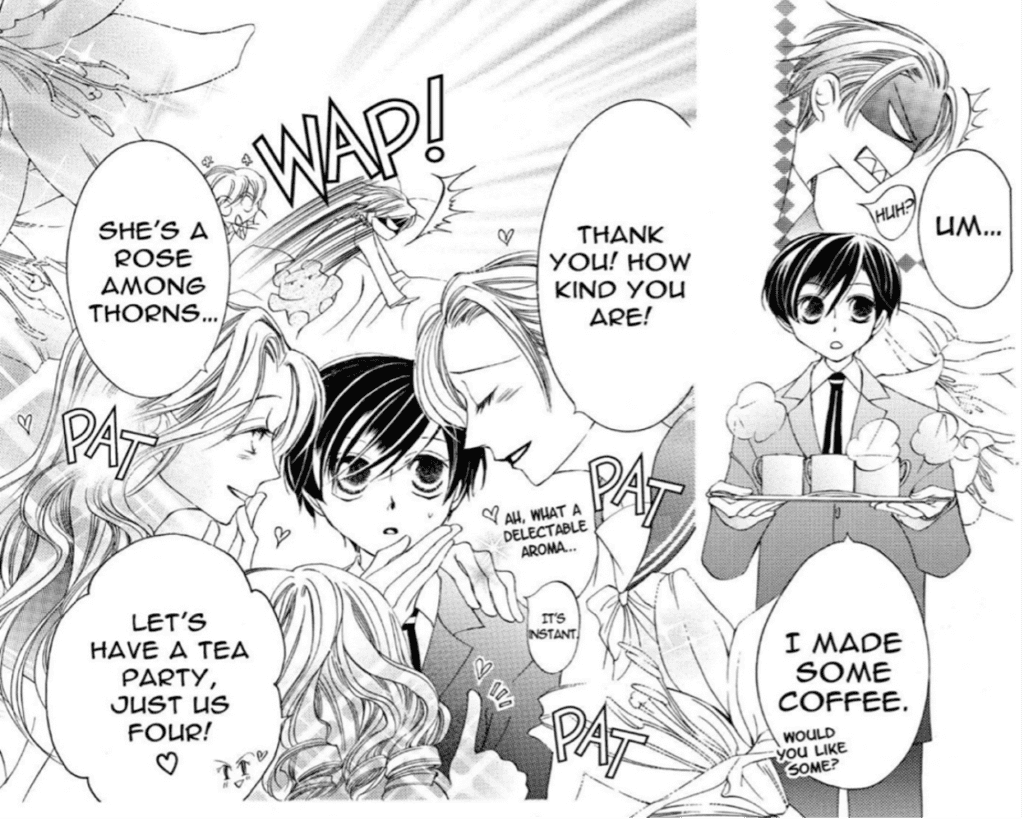

Figure 1: Kuranosuke’s grand entrance to save the day. Kuragehime (Vol. 1: 35).

Kuragehime & Intentional Performance

Running from October 2008 to August 2017, Akiko Higashimura’s 17-volume Kuragehime (Princess Jellyfish) is one of the most critically and commercially successful josei manga of all time, spawning an equally-critically acclaimed 11-episode anime adaptation in 2010, a live-action film in 2014, and a live-action drama series in 2018. [3] The story is in set in the Amamizukan, an all-female apartment complex populated by otaku (おたく), nerds obsessed with manga, anime, or other niche interests, who call themselves Amars (a nickname meaning nun). Though men are strictly prohibited in the Amamizukan, the manga chronicles the unlikely friendship and eventual business partnership between Tsukimi Kurashita, a jellyfish otaku (in other words, her obsession is jellyfish) struggling with grief and social anxiety, and Kuranosuke Koibuchi, the cross-dressing son of a local politician searching for a place to belong. The two are brought together by chance when Tsukimi is nervously and unsuccessfully attempting to save a jellyfish from maltreatment at a pet store and Kuranosuke, bold and confident, comes to her aid (Figure 1). After lugging the jellyfish and supplies back to Tsukimi’s nunnery of an apartment, the pair fall asleep, only for Tsukimi to discover the next morning, as Kuranosuke sits up wig-less with his bare chest on unabashed display, that he is biologically male. While this setup of a person assigned male at birth and dressed as a woman entering a women’s only space could easily spawn the sort of exclusionary, essentialist, and transphobic rhetoric that has been promulgated in the media as of late, Kuragehime instead presents a welcome and subversive feminist critique that allows for many definitions of femininity, and in turn masculinity.

Intentional gender-bender narratives often highlight the contradictions in our modern gender binary’s conceptualization in both abundantly unsubtle and utterly subtle ways. On the one hand, there are the more obvious critiques made by the gender-bending character(s) in question, who, by differing from the established cultural norms of the gender they were assigned at birth, reflect on, in Butler’s phrasing, ‘the imitative structure by which hegemonic gender is itself produced,’ thus disputing any claim biological essentialism has to ‘naturalness and originality’ (2002: 125). Kuranosuke is one such character, as he occupies a liminal space between the binary constructions of female and male in contemporary Japan. Rich, confident, and self-described as beautiful since birth, Kuranosuke is the pinnacle of upper-class, masculine privilege. And yet, as the second son and mixed-race child of an extramarital affair, Kuranosuke has always felt othered in his own home, an othering that is only intensified by his desire and affinity for feminine fashion.

In the 1999 preface to Gender Trouble, Butler poses the question: ‘[i]s drag the imitation of gender, or does it dramatise the signifying gestures through which gender itself is established?’ (2002: xxviii). The subversiveness of Kuragehime comes through the ways it engages with this question. Like many of those who perform drag, Kuranosuke does not identify as a woman, and yet he lives practically each day in clothing that was designated female, makeup that is considered feminine, and wigs that swish and swirl with the supposedly womanly shaking of his hips. When strangers perceive him as a woman, they are interpreting the signifying gestures of a culturally specific form of femaleness, ‘the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self’ (Butler 2002: 179). And while Kuranosuke is comfortable with others perceiving him as female, and at times explicitly denies his male gender identity, he is also not defined either by femaleness or maleness.

There is no current term in either Japanese or English’s limited and mostly binary conceptualization of gender that accurately describes how Kuranosuke lives, behaves, and perceives himself. Gender-fluid might be close, though this term was not widely used in Japan at the time of Kuragehime’s publication. Though other characters describe Kuranosuke as a ‘cross-dresser,’ when questioned, he quickly clarifies that crossdressing ‘is just my hobby’ (Vol.1: 52). Throughout the manga’s seventeen volumes, he in various ways reasserts that cross-dresser (noun) is not someone he is, rather cross-dressing (verb) is something he does. Similarly, he will admit that he dresses in drag (action) but deny that he is a drag queen (identity). This perception of oneself as expressed action rather than stable identity recalls a different passage from Gender Trouble: ‘[c]onsider the further consequence that if gender is something that one becomes—but can never be—then gender is itself a kind of becoming or activity, and that gender ought not to be conceived as a noun or a substantial thing or a static cultural marker, but rather as an incessant and repeated action of some sort’(Butler 2002: 143). In this manner, Kuranosuke’s embodied, enacted, and repeated performance that blurs the expectations of masculinity and femininity, exemplifies Butler’s vision of a gender-expansive future.

However, Kuranosuke’s insistence that he is ‘normal,’ alongside his vehement denials of the labels of crossdresser and drag queen, and the more specific Japanese slang term okama (お釜, effeminate gay man), can be seen as defensive, dismissive, and ignorant at best and offensive, homophobic, and transphobic at worst. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the manga, flawed as it may be in this regard, critically engages with the concept of normalcy, the hypocrisy of any claim to it, and Kuranosuke’s own relationship to ‘normal’ as a person with a decidedly non-normative approach to gender.

When Kuranosuke explains to the audience why he dresses like he does, he asserts that there are two reasons, the first being, ‘If I can convince people I’m a weirdo now, life will be easier in the long run’ (Vol. 1: 389). He believes that the shame of having a son like him will keep him from being used as a political puppet and allow him the freedom to escape his family legacy and instead enter the world of fashion, a life that his father would otherwise forbid. The second reason he gives is less flippant and repeatedly asserted throughout the series through his words and actions: Kuranosuke loves female fashion. His love of dresses, jewelry, makeup, skirts, scarves, and other aesthetic markers of femininity is so deep‑seated and intrinsic to his identity that he argues it is in his ‘genes’ (Vol. 8: 311). In a flashback in chapter 16, he grows indignant when told that as an adult he will wear tuxedos instead of the beautiful dresses his mother is showing him in her closet. The young Kuranosuke refuses to listen, insisting instead as his little hands grasp at the billowing skirts of his mother’s gowns, ‘No! When I grow up, I’m going to wear this! And this one! And that one!’ (Vol. 2: 115). This pattern continues through the manga’s 17 volumes. Though the explanations Kuranosuke gives for his behavior and preferences can both be true in a literal sense, their connotations directly contradict each other. While the first implies that his dressing as a woman is non-normative, the second challenges that notion, establishing that his desires are entirely normal to him, and have been with him since as far back as he can remember.

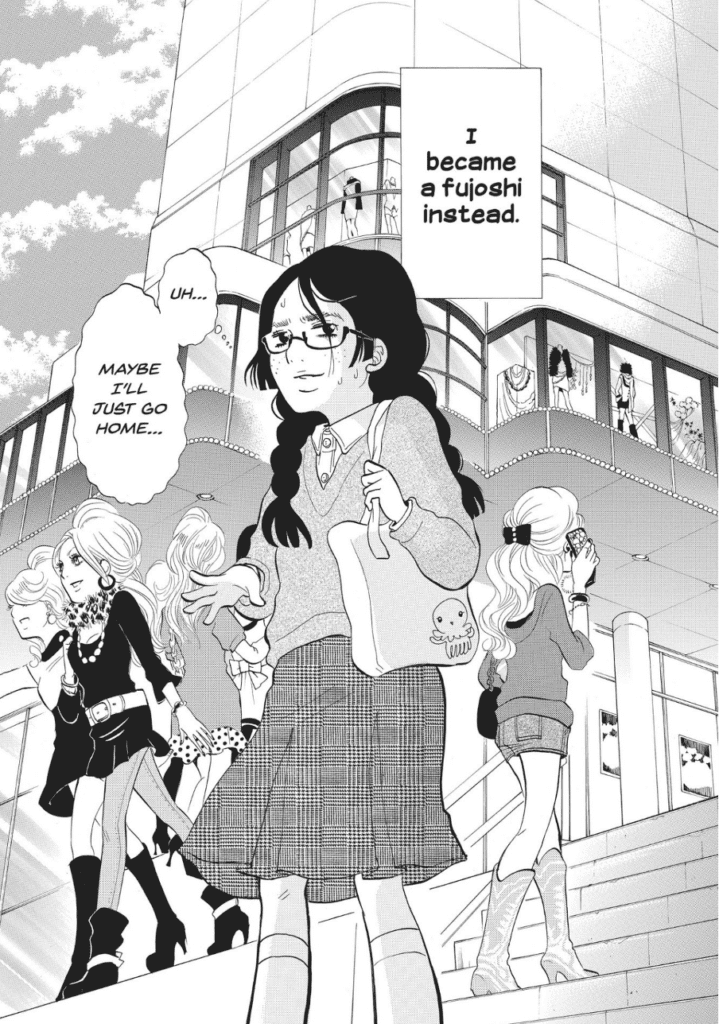

Figure 2: Introducing Tsukimi the fujoshi. Kuragehime (Vol. 1:13)

In addition to the direct critiques to binary systems that gender-bending itself provides, the interactions between the gender-bending and the non-gender-bending characters often highlight the more subtle ways that masculinity and femininity are constructs that differ not only from culture to culture, but from person to person. When we first meet Tsukimi, it is in a one-page spread of her as a child standing beside her now deceased mother at the aquarium. In the flashback, she is gazing away from the reader towards the frilly tendrils of a jellyfish that look like lace on a princess dress. Her mother remarks, in a glimpse of a memory that will reverberate throughout the story, ‘All girls can be beautiful princesses when they grow up.’ Ten pages later, we finally see Tsukimi for the first time as she shuffles through the crowded streets of a popular fashion district in Tokyo. Awkwardly scrunched and dripping with sweat, Tsukimi’s internal monologue positions her in opposition to social norms. Though Shibuya is full of women who are stylish princesses, Tsukimi, somehow, became a fujoshi (腐女子) instead (Figure 2).

Within these ten pages, Higashimura introduces and distinguishes the different presentations of femininity that the series will go on to explore and challenge: princess, stylish, and fujoshi. Translating to ‘rotten woman,’ the term fujoshi was invented as a ‘masochistic moniker’ in fan communities of shōnen-ai and yaoi (male-male romance) manga in the early 2000s to disparage their own interests as “corrupt” and morally reprehensible (Kayo 2010: 93). However, as a translator note in the first volume explains, Tsukimi and the other Amars refer to themselves as fujoshi not because they are interested in yaoi specifically, but rather because they ‘self-identify as individuals opposite from Japan’s patriarchal definition of what a “good woman” is’ (Vol 1:383). Embodying none of the ladylike innocence, outward focus, or unassuming purity associated with the traditional ideal of the ‘helpful wife and wise mother,’ the Amars represent the multifaceted ways one can be the antithesis of traditional Japanese femininity [4] (Vol 1: 383).

Interestingly though, despite their self-admonishments, the aspirational femininity the Amars desire but believe they can never embody is not this traditional patriarchal ideal. Instead, the term ‘princess’ represents for the Amars a sort of divine feminine, not constrained by one’s role in relation to others, but defined by self-confidence, fearlessness, and a strength to dress and behave however one wishes. On the other hand, those that the Amars deem ‘stylish,’ represent an antagonistic weaponization of cultural norms, as they adhere to the current standards of femininity and masculinity, and as such are believed to judge, ignore, or criticise anyone who does not meet those norms. When first describing Kuranosuke, before knowing his gender identity, Tsukimi describes him as, ‘Tall, fair-skinned, big-eyed. She could be a Barbie Doll,’ showing how the norms of stylish femininity are also linked to Westernised beauty standards [5] (Vol. 1: 51). However, Tsukimi doesn’t stop there, as—in awe of Kuranosuke’s help and bravery—she calls him a princess, and continues, ‘She’s using that beauty to live boldly and fearlessly. This girl is the exact opposite of me.’ Even once Tsukimi learns of Kuranosuke’s sex and gender, she continues to refer to him not only as a princess, but a male princess, and eventually as her princess as he teaches her to see those qualities in herself. And yet, for most of the manga, Tsukimi is unable to rectify her idealised image of divine femininity with her lived experience as a fujoshi.

As fujoshi, each of the Amars is distinctly obsessive, unsociable, considered conventionally unattractive, and, most importantly, emotionally unavailable to and predominantly unconcerned with the male population. This is made abundantly clear when Mejiro-sensei, the unseen leader of the household, declares via a slip of paper under the door that the guiding principles of the Amamizukan should be: ‘A life with no use for men’ (Vol. 1: 21). Tsukimi’s budding friendship with Kuranosuke and her eventual romantic storylines with both Kuranosuke and his brother, challenge this worldview in ways Tsukimi is petrified to examine. When she nervously asks for guidance regarding the punishment if someone were to hypothetically let a man into the apartment, the resulting answer is swift and decisive: ‘Death’ (Vol. 1: 65).

Kuranosuke, who dresses and behaves like a woman in everyday life, sees no problem with simply hiding his sex and gender so he can continue to visit. After all, as Butler argues, ‘gender ought not to be construed as a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts follow; rather, gender is an identity tenuously constituted in time, instituted in an exterior space through a stylised repetition of acts’ (original emphasis, 2002: 179). Yet, though Kuranosuke is shown to repeatedly perform these stylised acts to the satisfaction of external society, when he next enters the Amamizukan—donning his long, flowing hair, a hip hugging dress, towering heeled boots, and a full face of makeup—he is not welcome.

In order to be accepted as a member of the nunnery, Kuranosuke must not only implicitly identify as a woman and explicitly disavow men, but also agree to the collective’s rejection of the traditional expectations of femininity and the normative ways this femininity is performed. As such, the apartment complex functions not only as a sanctuary for the Amars from the judging eyes of society who view their presentations of femininity as suspect, but also operates as a place of judgment itself. Thus, the manga shows not his failure to reproduce and repeat the stylised repetition of acts, rather the ways in which these acts are always going to be instituted and interpreted in an exterior space.

The acts themselves, the aforementioned ‘bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds,’ which ‘constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self,’ take place through the body, but as a result, are outside of the body (Butler 2002: 179). Thus, regardless of the internal intention spurring an embodied performance, this performance will always take place in an exterior space that in of itself has the power to comprehend and ascribe meaning. Or as Wrede summarised, ‘[w]hen the body publicly articulates the social relationships of a certain time and place, the space in which that articulation occurs becomes the site of cultural inscription’ (2002: 10). Therefore, while Kuranosuke’s performance adheres to the standards of Japan’s upper-class, fashion-conscious society, he is not meeting those of the fujoshi culture inside the Amamizukan.

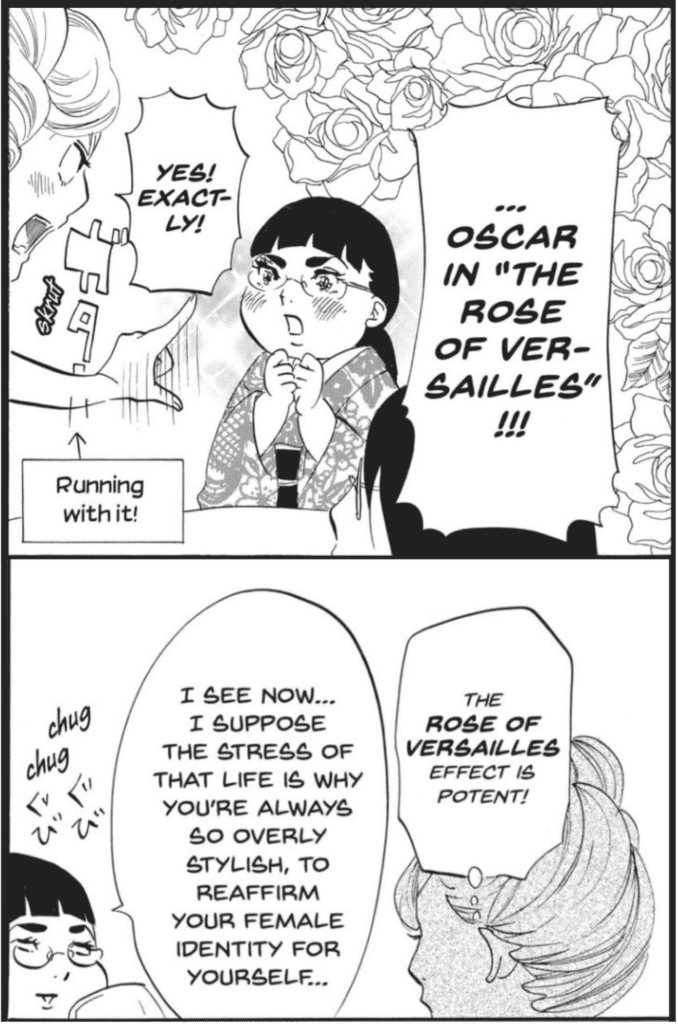

However, Kuranosuke is eventually formally invited into Amar society when they can see themselves in his feminine performance. When his father refers to him as his second son, unwittingly exposing Kuranosuke to the Amars, he is able to convince them that he is in fact a girl being raised as a boy for political reasons, due to the legacy and popularity of the gender-bending manga series with that plot, The Rose of Versailles (Figure 3). As this explanation appeals to their otaku interests, the Amars feel as though they finally understand his ‘overly stylish’ persona, choosing to interpret this performance as a stress response intended to reaffirm a feminine identity that his upbringing denied. Through this lens, the Amars view his dress and behavior as no longer normative and restricting, but as rebellious and liberating—which for Kuranosuke, they already were.

Once accepted as part of the Amamizukan’s inside group, none of the Amars question if Kuranosuke is a woman, despite the many times that his voice is noted dropping into a lower register, his silicone breasts are revealed, or he arrives at the house in masculine clothes. When a foreigner later questions the authenticity of Kuranosuke’s gender, one of the Amars rushes to his defense, stating, ‘There are some complicated and uniquely Japanese circumstances involved,” a reference to the aforementioned gender-bending manga (Vol. 4: 223). This appeal to the Amars’ otaku interests and their fujoshi imaginings of gender not only solidifies Kuranosuke’s identity against scrutiny, but also reveals how gender is an interplay between physical performance and desired perception. Incidental narratives, as we will explore through Ouran, highlight this process, demonstrating how gender is not just performed through the body in physical space, but is given meaning in this physical space as it is perceived in the social world.

Figure 3: Gender-bender manga shields Kuranosuke: (Vol. 2: 340)

Ouran & Incidental Naturalism

Bisco Hatori’s beloved 18-volume manga Ouran ran from September 2002 to November 2010, and like Kuragehime, was adapted to acclaim in the form of an immensely popular anime series in 2006, a live-action tv-drama in 2011, and a live-action film in 2012. Chronicling the trials and tribulations of the school’s Host Club, the manga was at once a satire of shōjo cliches and a love-letter to them, critiquing the demographic’s archetypes, tropes, and characters, while also treating the fantasies populating them with seriousness and care. In a story that directly presents us with the artifice before carefully peeling back the layers to authenticity, Ouran speaks to the assumptions we make about other people, and the ways those assumptions are filtered through our own desires.

The manga opens with Haruhi Fujioka, a poor scholarship student who cannot afford her school’s uniform, wandering the halls of the vast and luxurious Ouran Academy in a second-hand button-down and sweater which hang shapelessly from her body. Along with her unkempt short hair (cut roughly because a kid’s gum had gotten stuck in it) and her thick framed glasses (she lost her contact lenses before the school year began) her appearance throughout the first pages of the manga is relatively, but not intentionally, androgynous. Looking for a quiet place to study, Haruhi stumbles across the school’s Host Club, a group of rich, bored, and beautiful boys who cater to the desires of their rich and bored female ‘clients’ with tea, cake, and charming conversation. When she knocks into and shatters an expensive vase and finds herself indebted to the club, they force her to become their errand-boy. However, Haruhi quickly proves herself to be a natural at hosting, so the obvious solution is to give her a makeover—a male uniform, a new haircut, and some contact lenses—and put her to work paying off her debt. Only at the end of the first chapter, once she has proven herself quite capable of the task, is it revealed that Haruhi is in fact a girl. She responds to their shock by saying, ‘Can’t say that I fully appreciate the perceived differences between the sexes anyway.’ (Vol. 1: 55)

Incidental gender-bender narratives problematise essentialist gender arguments because they are grounded in such mistakes regarding the ‘truth’ of gender insomuch as this relates to biology. If one ‘fails’ to correctly attach a gendered label to the body they are perceiving, moreover if this failure comes without the presumed artifice of performance obfuscating one’s preconceived notions of biology, then one cannot argue the truthfulness of a biological definition for gender. Thus, incidental gender-bender manga exemplifies that, as Butler argues, ‘genders can be neither true nor false, neither real nor apparent, neither original nor derived’ (2002: 180). Furthermore, unlike intentional narratives, where the performed actions embodied by an individual are intended to directly correlate to perception, incidental ones happen without intention, highlighting that gender is also an apparatus that functions in the social world independently.

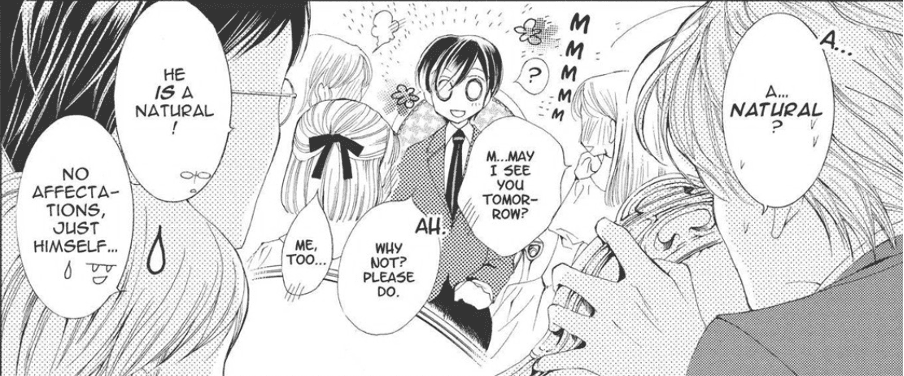

Yet, the social world is far from stable and often reflects the desires of those doing the imagining more than those being imagined. It is implied in the last panel of the first chapter, as Tamaki stares at Haruhi in disbelief upon discovering her student ID, that the entire Host Club, save him, realised that she was a biologically female without seeing it spelled out. Even so, for the remaining seventeen and a half volumes of the manga, very few other characters ever question the authenticity of Haruhi’s male persona. One could argue that this is because she is actively performing a male identity. After all, she is wearing a male uniform and using the first person singular pronoun ore (俺), a masculine ‘I’ pronoun that Kuranosuke gets in trouble for using. And yet, unlike Kuranosuke, who is shown to change his voice, alter his mannerisms, and adjust his performance depending on the situation, Ouran makes it clear that aside from the two changes mentioned above, Haruhi isn’t doing much of anything different than before. She just is a natural. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Haruhi proves to be a natural: Ouran (Vol.1: 38)

Manga scholar Ueno Chizuko has argued that male protagonists of shōjo are ‘neither male nor female’ but a ‘third sex/gender,’ asserting that ‘it is only a person’s mind, which is bound by the gender dichotomy, that mistakes that which is not a girl for a boy’ (qtd. in Welker 2011: 213). As Ouran is written to parody many of the tropes associated with shōjo manga, the characters themselves are self-aware of the character archetypes they embody, exemplified in the personas they perform to appeal to the fantasies of their female clientele. For instance, Tamaki’s prince character is more suave and debonaire than the excitable and clueless young man he is outside of the club’s hours, while the twins exaggerate their closeness with staged homoerotic subtext that they are shown to both despise when not performing. However, while each host is characterised to act as their type—an act that has elements of, yet is distinct from, their non-host personality—Haruhi is rarely portrayed to be acting. Instead, she is, as incidental protagonists often are, simply mistaken, as Chizuko puts it. Not meeting the expectations of a girl, she must be a boy. And yet Haruhi’s charm, as a boy, is her naturalism, as ‘the natural’ is the label used to advertise her to the female population. But, if she were so natural, how were the hosts able to identify her so quickly, while the rest of the school never does?

Butler argues that terms such as masculine and feminine are themselves flexible, with changing meanings dependent upon ‘cultural constraints on who is imagining whom, and for what purpose’ (2004: 10). Though Haruhi may neither identify as male nor perform many gestures or styles to construct maleness, by occupying a male role in the microcosm of society that is her school’s Host Club—an inherently gendered space that encourages fantasy production—her natural performance is imagined in this society as masculine. By occupying a popular and privileged role in her social space, and by being surrounded by figures who constantly affirm her performance, traits that would otherwise be viewed as feminine are instead signifiers of an attractive security in her masculinity. Throughout the series, characters who believe Haruhi to be male appreciate that she is adept at domestic skills such as sewing and cooking, and they gush and fawn over her slim body, more feminine face, and deep, glistening eyes, traits that are seen in this parody manga as desirable for a man to have, as they are the qualities often possessed by men in shōjo manga. Though these moments of admiration are often played off to the reader as in-jokes, and are easily explained by the narrative—she sews and cooks due to the financial constraints of a single parent household, she has a feminine limbs and face because she is biologically female, and her eyes glisten due to her contact solution—they are nevertheless feminine-coded attributes which are consistently affirmed by other characters as evident of how attractive she is as a man, never as reasons to question if she is a man.

Only a trio of girls from the rival Lobelia Academy see through her persona. (Figure 5) These characters—who perform male roles in their school’s Takarazuka theatre club and thus are likewise practitioners of non-normative gender performances—see themselves in Haruhi. As a result, they also project their own imaginings onto her, envisioning her as a woman trapped and oppressed by the normative gender structure of the Host Club. They repeatedly try to get Haruhi to transfer schools, believing she will be more comfortable at a school with people like her, ignoring Haruhi’s equally repeated assertions that Ouran Academy is where she belongs. (Vol. 3: 80). Like the clients in the Host Club who accept Haruhi’s performance because it aligns with their fantasies, the trio from Lobelia deny the truth of her performance, because it does not align with theirs. Though Ouran’s narrative repeatedly asserts—as Haruhi states in the first chapter—that appearances do not really matter because ‘it’s what’s on the inside that’s important,’ the series inadvertently demonstrates that they do, in so much as gender is tenuously constructed outside of oneself, in a social apparatus that perceives embodied actions not only through a cultural lens, but through the locus of the perceiver’s own desires (Vol. 1: 18). However, the struggle of negotiating these realities—gender being both an internal construction and an external condition over which one has very little control—is best exemplified in the involuntary category of gender-bender manga, explored here through Ranma ½.

Figure 5: Haruhi meets the Lobelia Academy Trio: Ouran (Vol. 3: 82)

Ranma ½ & Involuntary Conditions

Written and illustrated by the renowned mangaka Rumiko Takahashi, Ranma ½ is perhaps the most iconic and well-known gender-bender manga to date. Running from August 1987 to March 1996, this 38-volume manga, along with its long-running anime, became some of the first works of Japanese pop-culture to be licensed, translated, and disseminated to massive popularity worldwide. Among the booming martial arts media in the late 1980s, Ranma ½ stood out not only as a comedic addition to the genre, but as a subversion of the gender norms the genre tended to encourage. Like the protagonists of Dragon Ball Z and Fist of the North Star, Ranma is a hyper-masculine martial artist who can, with hard work and tenacity, defeat any antagonist that crosses his path. And yet, unlike his contemporaries, he spends half his narrative performing these feats of dazzling skill and macho bravado in the body of a curvaceous teenage girl. Cursed to uncontrollably transform into a female body whenever splashed with cold water and back into a male body whenever doused with hot water, Ranma is forced to grapple not only with his own assumptions and prejudices in relation to gender, but with those of the world around him. As an involuntary gender-bender narrative, Ranma ½ explores how gender is both created through and forced upon the body.

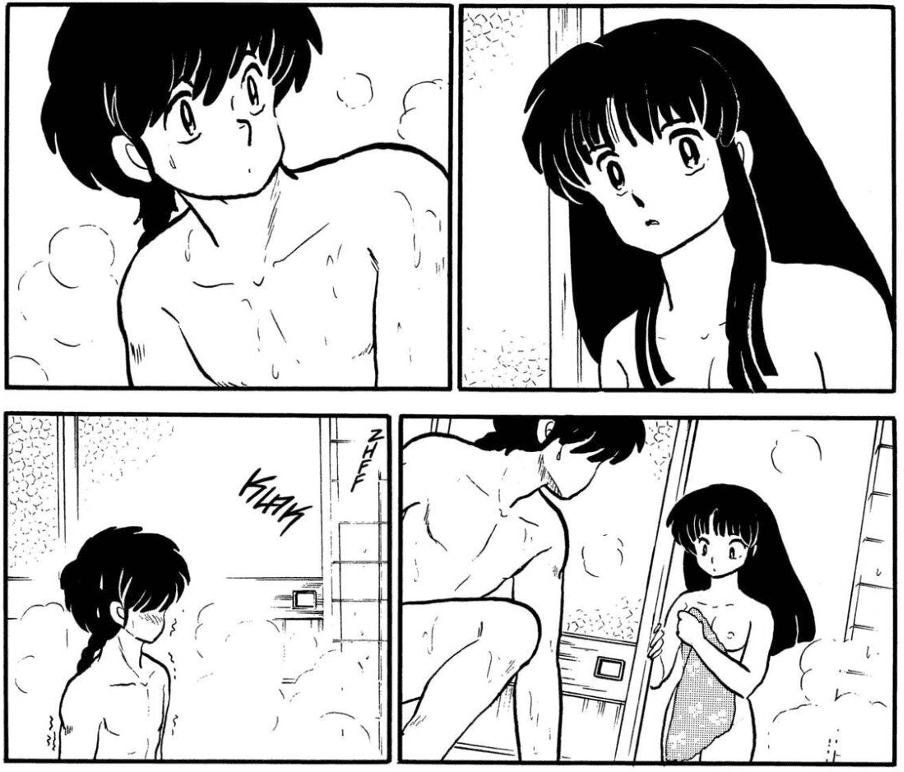

When we first meet Ranma he is being chased through the streets by his father, attempting to flee the social obligation of carrying on his family’s martial arts school through an arranged engagement. Our initial glimpses of him are in his female form—fleeing, fighting, flipping off his father—and it is not until the end of the first chapter, over twenty pages later, that we are introduced to Ranma in the body he prefers and identifies with. Before he goes into the bath, Ranma is bare breasted and busty, when he steps out, his flat chest is on display (Figure 6). Akane, the girl he will become engaged to, is shocked to see it, in a manner that is very similar to Tsukimi’s shock at seeing Kuranosuke’s own male anatomy. However, unlike in Kuragehime, where a wig and breast enhancers can be viewed as an obfuscation, an addition to the body for the purposes of self-transformation, in Ranma ½, it is the body itself which does the transforming.

According to Butler, the body is the ‘site where “doing” and “being done to” become equivocal’ (2004:21). Though she urges for a worldview where ‘the constructed status of gender is theorised as radically independent of sex,’ so that gender will become a ‘free-floating artifice’ and thus, ‘man and masculine might just as easily signify a female body as a male one,’ she also understands that this view currently has its limits (Butler 2002: 10). She acknowledges that by living in bodies that occupy social spaces, ‘the body has its invariable public dimension; constituted as a social phenomenon in the public sphere’ (2004: 21). As such, the body is both made a subject by, and subjected to the norms and expectations of, the society it occupies.

Figure 6: Ranma’s male form is revealed: Ranma ½ (Vol.1: 34)

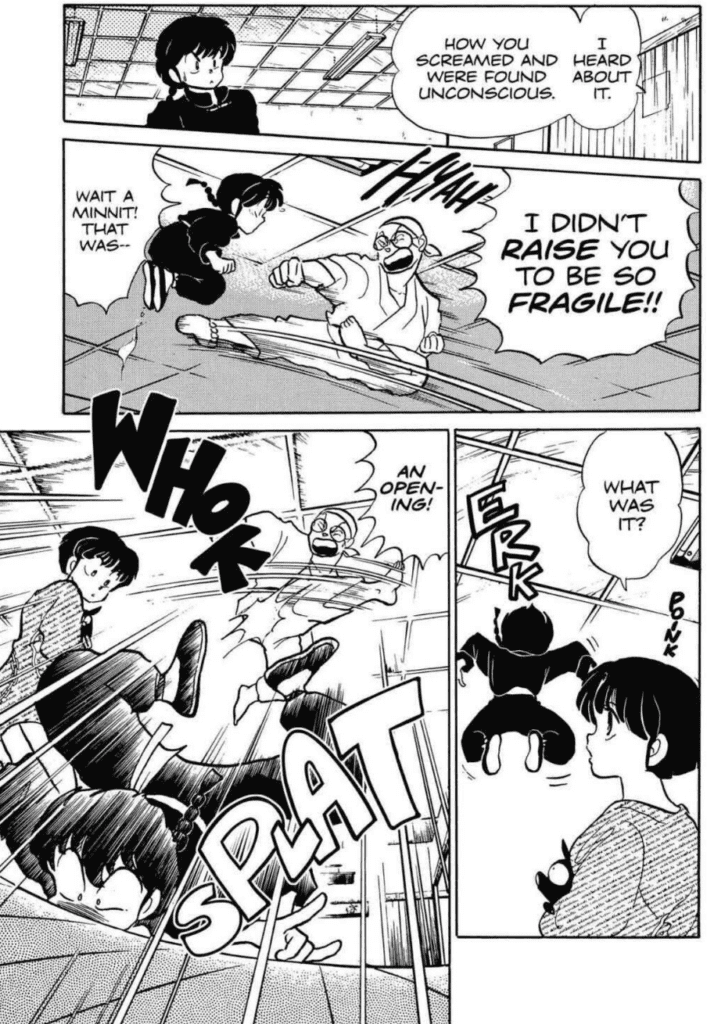

In Ranma ½, the gender norms and expectations that created and constrained Ranma’s identity are often directly shown to have been instituted by the protagonist’s father. A narcissistic chauvinist, Genma is determined to raise his son into ‘a man amongst men,’ so much so that he stripped Ranma away from his mother as a young child, promising only to return when the task was accomplished, or else he and Ranma would both commit seppuku (切腹, belly-slitting, ritual suicide). For most of the series this looming threat is unbeknown to Ranma, yet he is nevertheless determined to prove his ‘manhood’ to his demanding yet neglectful father, a man who more than once traded his son for a loaf of bread. Most of the internal and external conflicts that arise throughout the manga are a result of Genma’s hubris, misogyny, and maltreatment, including Ranma’s many fiancées, his casual sexism, his defensiveness, his inability to express his emotions, and most significantly, his curse. Though Genma brought Ranma to, and knocked him into, the cursed spring and is thus responsible for all the subsequent sexed transformations, he nevertheless verbally and physically berates his son for the consequences of his own actions. Additionally, he is swift to punish any crack in Ranma’s carefully constructed performance of masculinity, blaming this ‘failure’ on Ranma’s female body (Figure 7). While Genma is himself cursed to turn into a panda, he views his own transformation as inconvenient. Ranma’s curse and the implication of femininity are an abject disgrace.

It is in this manner that Ranma ½ exemplifies how the prejudices of prior generations regarding sex and gender can become the burden and trauma of another. Ranma cannot help but internalise the construction of manhood in which he was brought up, fearing the social consequences of a non-normative gender performance. Compared to Kuranosuke—whose divergence from gender norms has few negative consequences and who views even those consequences that are negative as still to his benefit—Ranma has far more at risk. When he strays from the narrow path of macho masculinity—be it by eating sweets, wearing the wrong clothes, hugging a friend, or receiving aid when injured—he is convinced that he will be mocked because, as we are shown, he has been belittled and derided before. As such, Ranma self-regulates, only performing these actions after willingly transforming into his female form. Though he doesn’t prefer this body, he would rather his actions not be viewed as non-normative, even if no one else is around to notice because, as Butler argues, ‘one does not “do” one’s gender alone,’ and instead, ‘one is always “doing” with or for another, even if the other is only imaginary’ (2004:1). Akane will often acknowledge the absurdity of the gender norms Ranma is opposed to while expressing empathy regarding them. Several times throughout the series, she pours water on him when he is injured, circumventing his rejection of support. It is through Akane, her understanding and her own resistance to gender norms, that he comes to accept some of that which is non-normative within himself.

Figure 7: Genma’s approach to fatherhood: Ranma ½ (Volume 3: 29)

Nevertheless, the manga does not make the argument that the only violence against the body is done through instituted norms, and instead regularly shows how gendered bodies can be subject to external violence. When the series begins, Ranma is shocked to learn that Akane, a powerful martial artist herself, must fight off a hoard of boys every morning to physically enter the school because they believe whoever finally defeats her gets to date her. He soon comes to understand her predicament, as, throughout the 38 volumes, Ranma and Akane are both constantly being pursued, catcalled, groped, and propositioned by characters who will not take no for an answer. Although Ranma is also romantically harassed and sexually objectified in his male form, the overwhelming instances occur when he is in his female one, demonstrating how simply existing in a female body can be dangerous in a patriarchal world.

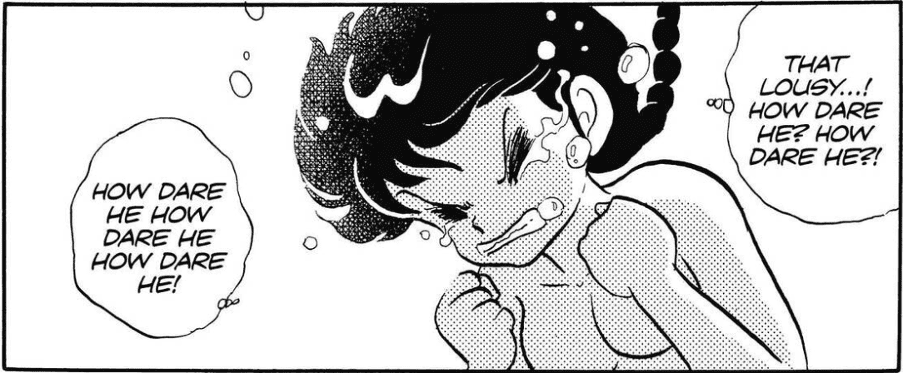

Figure 8: Ranma’s response to non-consensual kissing: Ranma ½ (Vol. 2: 142)

When Ranma’s first kiss is forced upon him by a boy, he freezes, the panel cracks, and he flees the scene sobbing, utterly shaken (Figure 8). Though the argument can be made that the scale of his reaction is evident of the manga’s homophobic humor, and indeed several characters laugh and mock Ranma for kissing a boy specifically, I think it is equally significant to note that Ranma expresses several times that he is upset because his first kiss was stolen, i.e., non-consensual. He even grudgingly admits to Akane—the only character not laughing at the situation, but who also thinks he is distressed because it was a boy—that he had wanted his first kiss to be with someone he loves. But, of course, he can never tell anyone else this, because that too would go against his construction of masculinity. Thus, Ranma ½ and involuntary gender-bender narratives tell stories about the constant struggle of gender formation. They acknowledge that who we are is not always who we want to be, and that who we want to be is not always who we are expected to be. And yet, despite the pitfalls and the paradoxes, we keep striving to identify ourselves anyway, for as Butler writes, ‘[i]f I have any agency, it is opened up by the fact that I am constituted by a social world I never chose. That my agency is riven with paradox does not mean it is impossible. It means only that paradox is the condition of its possibility’ (Butler, 2004: 3).

Conclusion

Possibility is the radical and subversive core of gender-bender manga. These narratives illustrate alternatives to binary definitions of gender and critically comment on how gender influences our lives. Though Rumiko Takahashi wrote Ranma ½ in the 1980s and 90s, Bisco Hatori wrote Ouran in the 2000s, and Akiko Higashimura wrote Kuragehime in the 2010s, their stories remain relevant, even if they do show their age and biases. Though they, like many gender-bender manga, are far from perfect—if perfect is what one desires or expects one’s media to be—they still touch upon the complex and intriguing ways gender has functioned, and currently functions, subtly and unsubtly interrogating our hopes, fears, and preconceptions, while imagining how gender could function if we were open to embracing the possibilities.

And that, to borrow Butler’s excitement and phrasing, is part of the ‘giddiness’ of gender-expansive work, as these narratives interrogate the ‘cultural configurations of casual unities that are regularly assumed to be natural and necessary’ (2002: 175). As explored through Kuragehime, Ouran, and Ranma ½, gender-bender manga’s subversiveness comes from these interrogations, challenging the norms and questioning their necessity. And perhaps this subversiveness is the very reason why manga’s gender-bender narratives have not been widely adopted by Western popular culture. Nevertheless, it is exactly the reason I hope these stories do become more prevalent around the world soon. Though I doubt Butler would view these works as being quite as subversive as I do, they provide the first steps towards the world that Gender Trouble and Undoing Gender propose. [6]

Perhaps by the time we get to that world, these narratives will be a relic of a distant, irrelevant past, and gender-bender stories will fade away like many other subgenres have done in the past. Or perhaps they will persist, as they have since antiquity, because we are always looking for models to understand our own becoming.

Notes

[1] Though both Kabuki and Takarazuka Revue theatre are sex-segregated and have histories inextricably linked to patriarchal structures, scholars have also discussed the possibility of gender subversion within these art forms, especially when considering the actors in both theatres whose approach to gender often blurred the lines between the stage and their everyday lives. For example, Yoshizawa Ayame, an early kabuki actor (1673-1719) who is often credited as the first great onnagata, stated that, ‘If [the actor] does not live his life as if he was a woman, it will not be possible for him to be called a skilful onnagata.’ (qtd. in Episale 2012: 96) Similarly, famed otokoyaku, Matsu Akira (working from 1978 to 1982), stated that she couldn’t do female roles because: ‘Even though I am a female, the thing called ‘female’ just won’t emerge at all.’ (qtd. in Robertson 1989: 64)

[2] For those unfamiliar, manga comes in five main demographics, four of which are explicitly gendered. Aside from kodomo (子供) the educational and often moralistic manga for children under the age of twelve; the four other demographics are targeted to a desired reader base, separated by gender and age, with thematic associations that themselves carry gendered baggage. To quickly explain (and as a result, oversimplify), shōnen (少年) for teenage boys, often has action driven narratives that focus on adventure, friendship, and coming of age through defeating external obstacles, while shōjo (少女) for teenage girls, often tells more emotionally driven narratives that focus on drama, romance, and coming of age through interpersonal development. Though more sexually explicit and morally complex than their younger counterparts, the demographics for adults follow similar patterns, with seinen (青年) for adult men, featuring more graphic violence, personal struggle, and political themes, while josei (女性) for adult women, explores the challenges of adulthood, interpersonal struggles, and relationship dynamics.

[3] The volume numbers listed refer to the original Japanese publications. The page numbers listed come from the English editions, which were all consolidated into fewer volumes.

[4] The translator note is referring to the ideal of ‘ryōsai kenbo,’ translated as ‘good wife and wise mother,’ which was promoted throughout Japan in the early twentieth century. According to feminist manga scholar Masuko Honda, ultimately, ‘all one needed to do to become a ryõsai kenbo was to get married.’ (2010: 14). Notably, in the last volume of Kuragehime, Tsumiki turns down a proposal, rejecting this ideal from a place of self-confidence, instead of self-deprecation.

[5] While we do not have the space here to explore how Westernised beauty standards such as this are repeated throughout the series, it would be remiss to not mention that these statements, though warranting further exploration, do not go unchallenged by the narrative. As the series deals with the fashion industry, the characters confront, in both indirect and direct ways, how colonialism and westernisation have shaped ideals of beauty.

[6] In Gender Trouble and Undoing Gender, Butler calls for a departure from the restrictive norms of heterosexual matrix, and she distinctly criticizes movies like Victor/Victoria and Some Like It Hot in Bodies that Matter for using drag and homosexual-panic to uphold heterosexual frameworks. And I can see those arguments regarding the three manga discussed here, as each includes denials of homosexuality alongside homophobic humor, often with few consequences. Moreover, the central romantic pairings in each are technically ‘straight,’ in that each involves someone assigned female at birth (and technically female identifying) falling in love with someone assigned male at birth (and technically male identifying). However, none of these characters ever identify as straight and assuming such ignores the possibility of bisexuality, pansexuality, etc. Furthermore, I’d argue that the transgressive nature of the gender-bending in each of these manga, and the ways in which it shows individuals as falling in love regardless of their non-normative gender expressions, is nonetheless still quite subversive as this paper demonstrates. If gender is to be reimagined, I think this radical reimagining should come from all directions and benefit all sexual orientations.

REFERENCES

Butler, Judith (2002 [1990]), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Tenth Anniversary Edition ed., New York: Routledge.

Butler, Judith (2004), Undoing Gender, New York: Routledge.

Episale, Frank (2012), ‘Gender, Tradition, and Culture in Translation: Reading the ‘Onnagata’ in English’, Asian Theatre Journal, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2012, pp. 89-111.

Fujimoto Yukari, trans. Julianne Dvorak (1991), ‘A Life-Size Mirror: Women’s Self-Representation in Girls’ Comics’, Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Vol. 4, pp. 53-57.

Fujimoto Yukari, trans. Linda Flores, Kazumi Nagaike, Sharalyn Orbaugh (2004), ‘Transgender: Female Hermaphrodites and Male Androgynes’, U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, No. 27, pp. 76-117.

Fujimoto Yukari, trans. Lucy Fraser (2014), ‘Where Is My Place in the World? Early Shōjo Manga Portrayals of Lesbianism’, Mechademia, Vol. 9, pp. 25-42.

Hatori Bisco (2002-2010), Ōran Kōkō Hosuto Kurabu [Ouran High School Host Club] 18 Vols, Tokyo: Viz Media.

Higashimura Akiko (2008-2017), Kuragehime [Princess Jellyfish] Translated by Sarah Alys Lindholm, 17 Vols. Tokyo: Kondasha Comics.

Honda Masuko (2010), ‘The Invalidation of Gender in Girls’ Manga Today, with a Special Focus on ‘Nodame Cantabile”, U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, No. 38, pp. 12-24.

Robertson, Jennifer (1989), ‘Gender-Bending in Paradise: Doing ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ in Japan’, Genders, Vol. 5, pp. 50-69.

Saito Kumiko (2014), ‘Magic, ‘Shōjo,’ and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society’, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 73, No. 1, pp. 143-64.

Takahashi Rumiko (1987-1996), Ranma ½ [Ranma ½], 38 Vols, Tokyo: Viz Media.

Takeuchi Kayo (2010), ‘The Genealogy of Japanese ‘Shōjo Manga’ (Girls’ Comics) Studies’, U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, No. 38, pp. 81-112.

Welker, James (2006), ‘Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: “Boys’ Love” as Girls’ Love in Shôjo Manga’, Signs, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 841-70.

Welker, James (2011), ‘Flower Tribes and Female Desire: Complicating Early Female Consumption of Male Homosexuality in Shōjo Manga’, Mechademia, Vol. 6, pp. 211-28.

Wrede, Theda (2015), ‘Introduction to Special Issue ‘Theorizing Space and Gender in the 21st Century,’ Rocky Mountain Review Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 10-17.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey