Gaze Light & Cheek Gaze

by: Wuon-Gean Ho , October 5, 2020

by: Wuon-Gean Ho , October 5, 2020

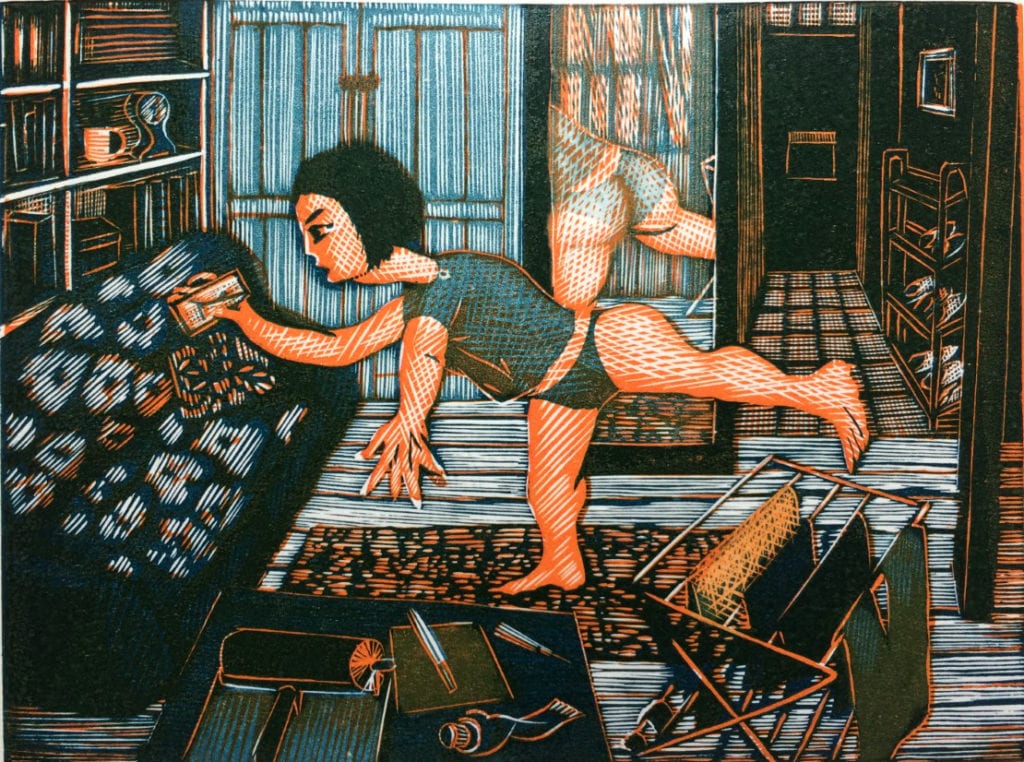

Wuon-Gean Ho’s creative practice investigates the everyday experiences of a non-white woman in a developed, post-digital world, now responding to physical distancing with an increasing dependency on the screen. The prints below are part of a series of over 110 images which she made for her father, who remains in a care home after breaking his neck in 2014.

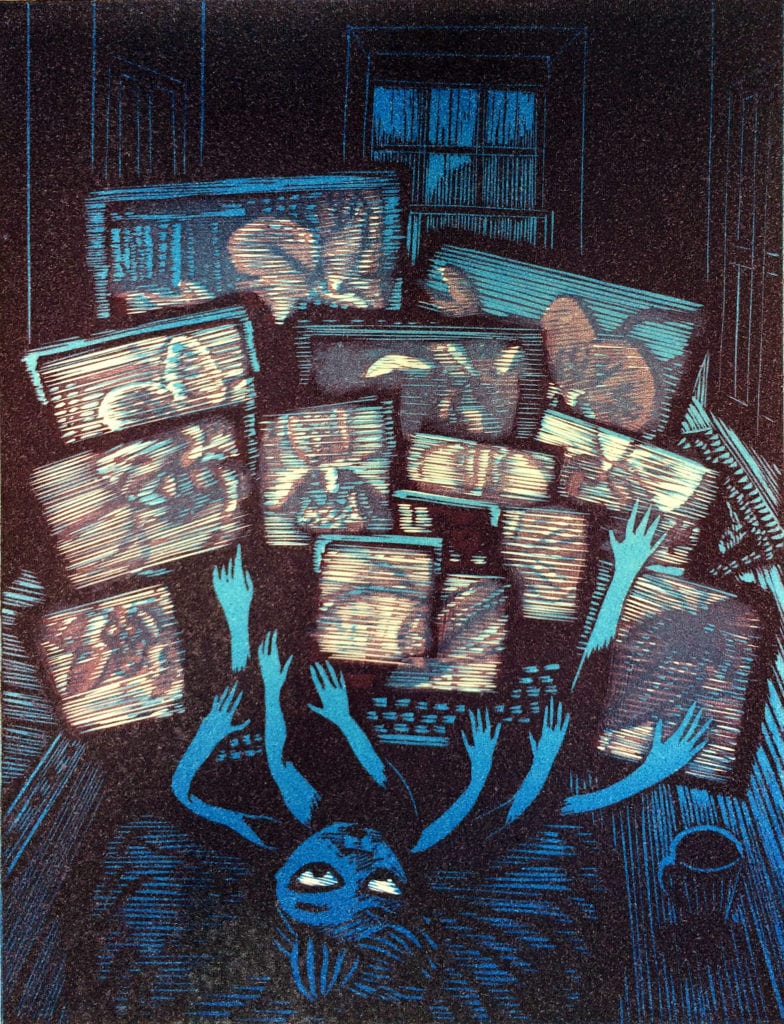

During lockdown’s enforced lack of touch, I found myself living through the screen, searching for connections through mediated digital worlds. With each new click, a fresh screen appeared, a plethora of arguments, groupings, statements. Like an insect, I could zoom into tiny spaces, examine the microscopic and hyperreal, be in simultaneous time. The web is a horizonless space. Inside, there is no smell, no touch, no taste—rather—cerebral, intellectual, penetrative vision and casually shifting points of view.

Unblinking, somewhat addicted, I let the screen overwhelm me, like a therapeutic machine: intelligently positing, highlighting, repeating, confirming, reframing. My body was attenuated. My eyes multiplied. I experienced pluripotency. The lack of hapticity was bewildering. In the interconnection, the fracture of self is complete.

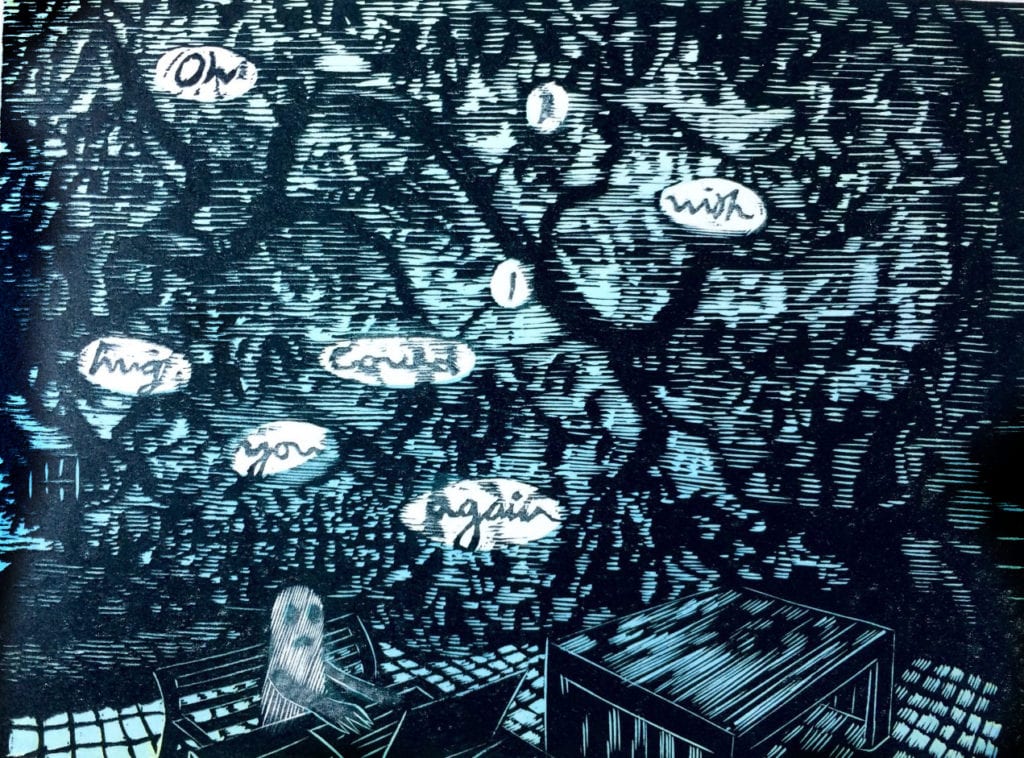

I skyped my father in the care home and tried to stroke his cheek. I found myself running a greasy fingertip trail over the polished glass of my laptop. Why is the video call so horrible, leaving me with a sense of loss and devastation? I turned to the screen to find out, and read about the uncanny valley, the perceptual mismatch between human appearance and robotic motion, which works on the human action perception system (APS), causing deep affective distress from the disgust at realising we were duped.

For touch to be imagined in the virtual world we need a more inaccurate, even clumsy, sense of movement. How can we experience corporeality without gravity and bulk: without the distance of a sigh, the movement of a flung arm, a hop, a fidget, a stride? The screen moves smoothly instead, like a floating angel.

‘Is anyone washing your face’, I asked. ‘They just let the water run over it in the mornings’, he replied.

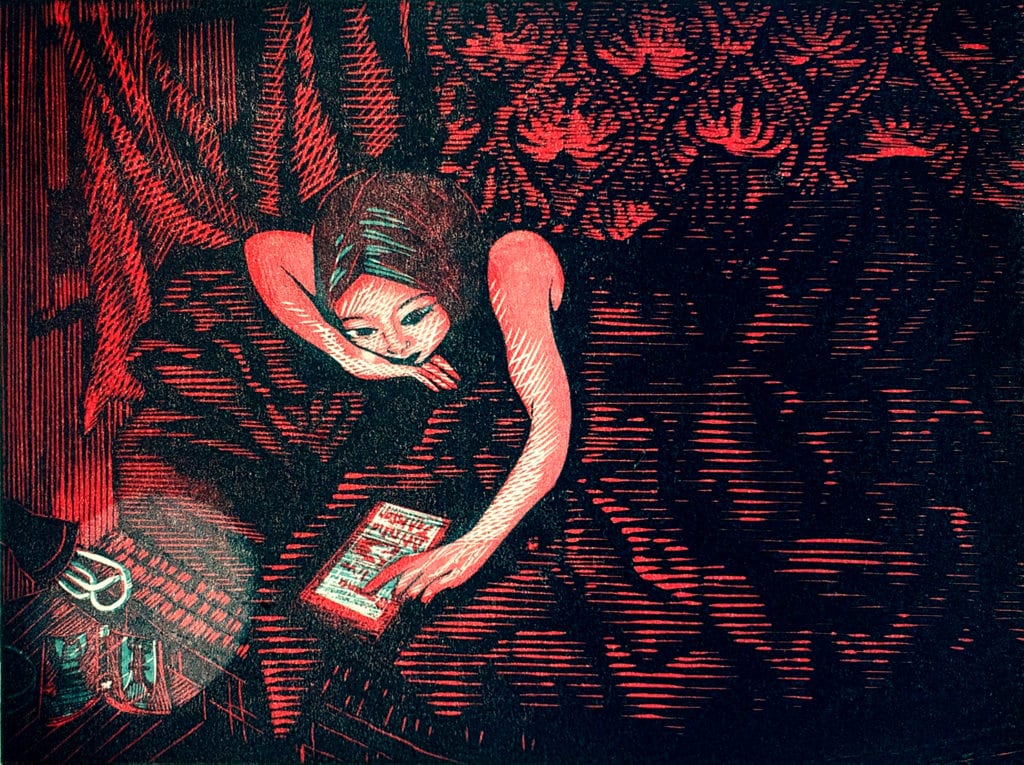

On my weekly visits, I would wield a warm damp towel and wash his face. I’d ask him to raise his eyebrows to let me get to the unnamed dip between corner of eyelid, eyebrow and bridge of nose, and circle gently down the slope towards the cheek. Then briskly, brusquely, tenderly, inexpertly I would pat anti-aging moisturiser in. I’d often massage along the jaw line and press gently on the third eye, and with each touch imagine the touch on my own face. Afterwards, I’d get back to the process of drawing him, to the soundtrack of Eva Cassidy and his childhood stories, or the predictable plotline of a Cowboy and Indian film that he might have seen that week. The touch of my gaze, tracing the planes and contours of his face, would also anchor his presence with my vision: he would feel felt, and he would feel seen.

The crescent of skin which sits below the eyes and follows the apples of the cheeks, curving towards both ears from the bridge of the nose in a double-U: this area of the face feels like the bit of my face that hungers for the touch of the gaze. In addition, perhaps this is just a wild and personal theory, but intuitively I feel that this part of my face is also responsible for giving a portion of my gaze. For why does intense looking with just the eyes, which we are doing on video calls all too much, feel empty? I believe we crave a gaze that tenderly brushes the cheeks, a sort of cheek-gaze.

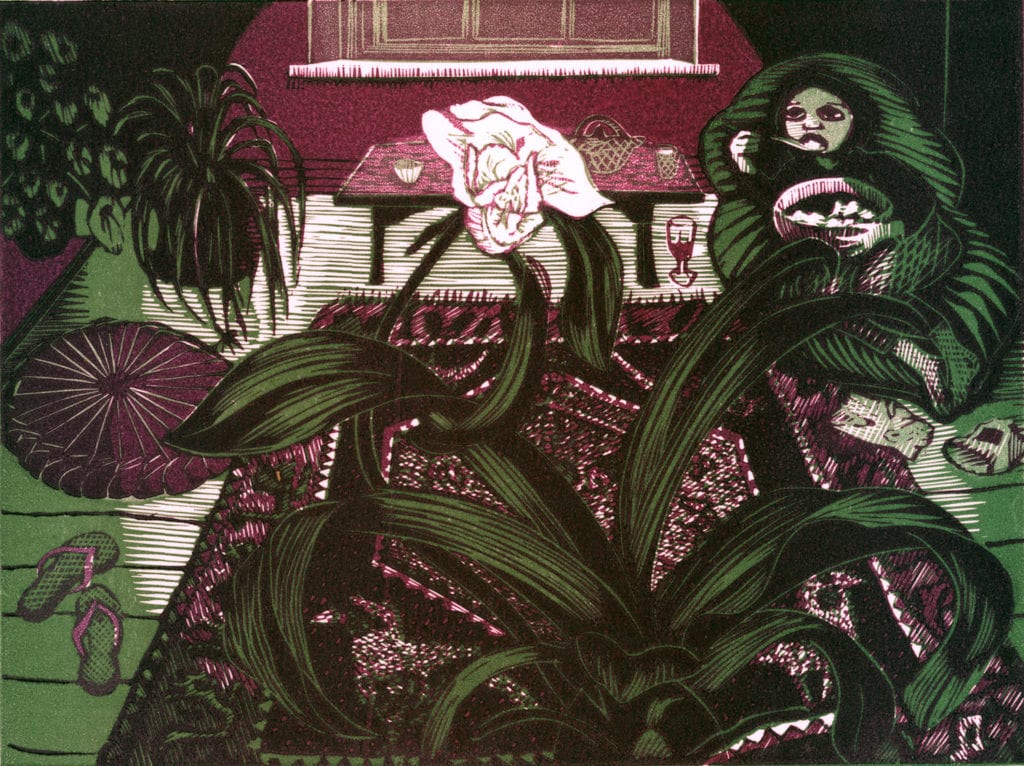

The cheek, home to the plumpest bellies of muscles to do with smiles and contentment, has overtones in vernacular English of playful rudeness, over-confidence, even brashness. The cheeks both give and receive the touch of looking. Even with my eyes closed, I can feel this gaze on this part of my face when addressed by my family or friends. It is the true meaning of extroversion: the part of the face that bellows out to meet the world and pushes vision outwards to caress the viewed.

When’s the last time my cheeks were irradiated with the gaze of another human being? It’s not the same being viewed by screen, being viewed by the dance of lit-up pixels. The lack of gaze-light on the skin is causing me to feel fractured and faceless, like a paper bag ghost. The lack of giving a cheek-gaze is also a sensation of holding the gaze back, unable to let this gaze fly outwards to touch the world.

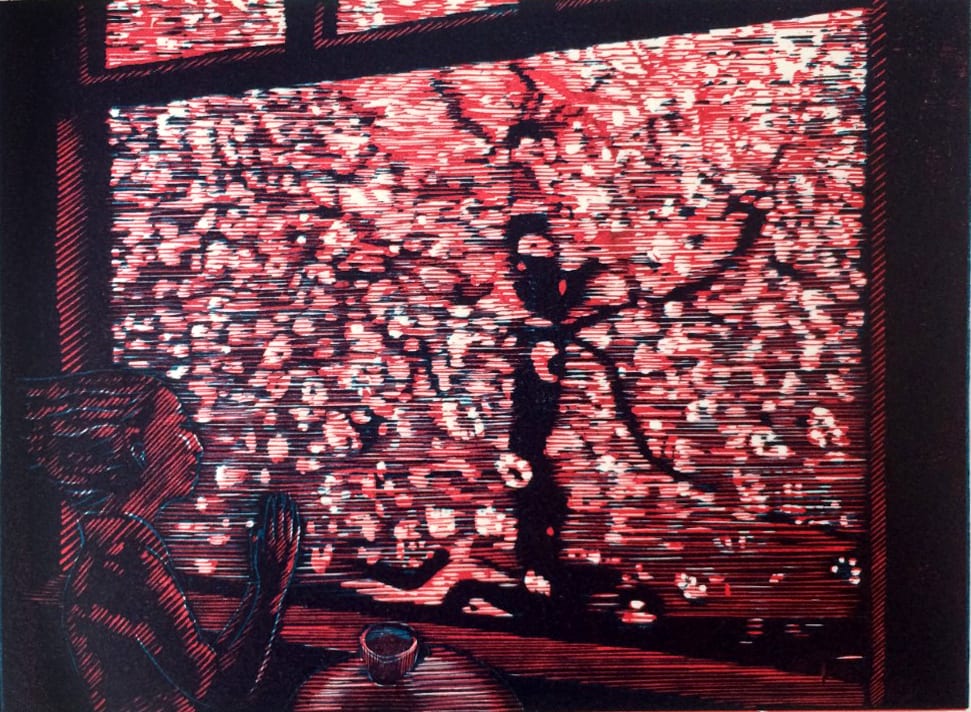

Sometimes I touch my cheek to the optimistic orchid blossoming at the west-facing window. We have each entered the other’s zone of honesty, the area within which auras and microbial drift can be perceived, where pheromones can be sensed, and perhaps even microscopic gravitational forces and magnetic or electrical disturbances can be felt. I realise that the narrowed gap of air between us is the distance of a caress, and that within this intimate cheek-gaze, we can smell each other.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey