‘From the Inside Out’: Skin & Horror in Emily Carroll’s Comics

by: Erika Kvistad & Jennifer Duggan , March 30, 2023

by: Erika Kvistad & Jennifer Duggan , March 30, 2023

‘What seems to bracket [body genres] from others is an apparent lack of proper aesthetic distance.’ (Linda Williams, ‘Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess,’ 1991)

‘But the worst kind of monster was the BURROWING KIND. / The sort that crawled into you and made a home there. / The sort you couldn’t name, the sort you couldn’t see. / The monster that ate you alive from the inside out.’ (Emily Carroll, ‘The Nesting Place,’ Through the Woods, 2014)

***

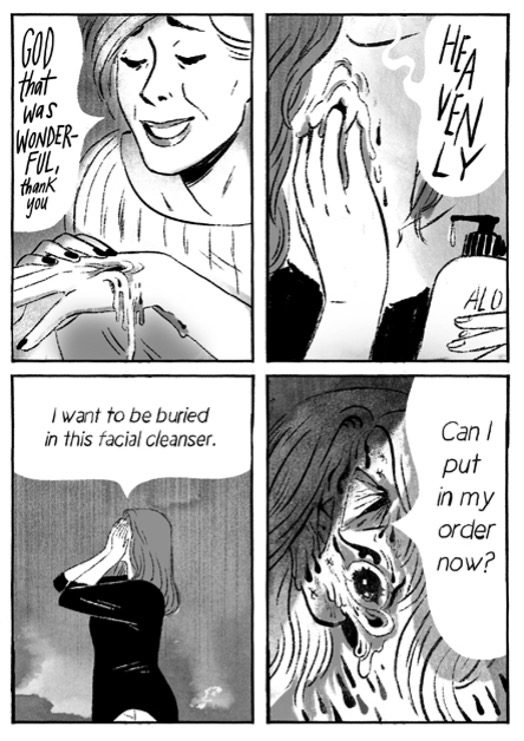

In Emily Carroll’s 2014 webcomic ‘All Along the Wall,’ we meet a ‘little monster’—Lottie, a girl whose mother worries that she might ‘knock something over or make some sort of mess’ in the house they are visiting for a Christmas party. Her mother’s friend reassures her that ‘mine was [difficult] at that age too! She’s grown out of it, thank goodness—I don’t mind saying she used to be impossible! Now though—what an angel!’ Lottie soon meets the ‘angel,’ Rebecca—who looks like a porcelain doll, with long lashes and fair curls—and asks her to entertain her with a ghost story. In the story Rebecca tells, a little girl is infested with something horrific. Her body breaks open, ‘and the Things that crawled out of her were beyond her mother’s WILDEST imaginings.’

Rebecca does not say it, but the reader learns that this story echoes the truth, and that this is what made her so angelic: she fell into a cave and became infested with red, threadlike worms that are now puppeting her skin. In a mouse-over image, we see a younger Rebecca in the cave, with red wormlike threads crawling out of the water and into her mouth and eye sockets. Behind Lottie’s back, the red mass of threads hidden behind Rebecca’s doll-mask unfurls and reaches out. The arrival of the housekeeper interrupts them, but not before Rebecca, doll-face back in place, fixes Lottie’s hair for her: ‘do you know where the REAL horror lies…? / In your bow! / It’s a mess! Here, let me fix it before your mother sees.’

Figure 1: From ‘All Along the Wall,’ reproduced with permission.

This scene gives us a feel for the importance of skin in Emily Carroll’s work. Carroll is an acclaimed web and print comic artist who has currently been active for a little over a decade; her body of work includes the Eisner and British Fantasy Award-winning graphic collection Through the Woods (2014), as well as a number of viral webcomics. Besides fairy-tale themes, body horror is perhaps the most prominent recurring feature in Carroll’s work. She is especially fascinated with skin: skin as texture, as surface, as concealing mask, as point of connection to and separation from the world, as prison. Her work depicts a phantasmagoria of monstrous skin: in ‘Out of Skin’ (2013), the corpses of murdered women transform into a consuming skin-house; in ‘The Worthington’ (2018) a woman sees her own face in the mirror as a rippling, melting mass; in ‘All Along the Wall’ (2014) and its sequel, ‘The Nesting Place’ (2014), a thin layer of human skin covers up a pulsating mass of worm-monster; even the ordinary skin on the back of an ordinary hand becomes unsettlingly alien in ‘Some Other Animal’s Meat’ (2016). Carroll’s characters experience skin, that of others but also their own, as unsettling, uncontrollable, deceptive, and entrapping. At the same time, as the scene above suggests, true monstrosity often appears in these texts in the familiar and innocuous form of normative femininity: it turns up wanting to fix your hair bow, as well as to turn you into a skin puppet.

This essay will focus on two of Carroll’s stories, the print comic ‘The Nesting Place’ (TNP) (2014) and the webcomic ‘Some Other Animal’s Meat’ (SOAM) (2016), to explore how Carroll’s horror works through the skin—the skin we see depicted on the screen and on the page, but also the reader’s skin. In an interview on body horror, Carroll (2019) describes our relationships with our own embodiment as a potential source of horror in itself:

I have, like anyone else, a lot of struggles with my body, and negotiating the perception of it, publicly and privately, can be an unsettling experience for me. It’s frightening to rely so completely on a vessel that we don’t even entirely understand, and which can change and surprise us at any time.

This image of the body as, essentially, a haunted house that you can’t leave and within which there could be a jump-scare at any moment is central to Carroll’s work. Here, to explore the links she creates between skin, horror, monstrosity, and gendered embodiment, we read Carroll’s work as queer feminist Gothic horror. We situate her work within a long Gothic tradition of monstrous bodies, while arguing that the embodied horror her skin work conveys is a specifically queer and feminist horror, a horror in which the protagonist’s body is beset, and is itself rendered horrifying, by the pressures of a monstrous gender, cis-, and heteronormativity.

The queer elements of Carroll’s storytelling are often more implicit than the feminist elements. Her protagonists are often, though not always, women dealing with different forms of gendered oppression, but her characters’ sexualities are not strongly thematised in the works we discuss here: Stacey is married to a man, while Bell’s sexuality is never made explicit. However, horror often appears at the juncture between cis- and heteronormativity, with being beautiful to attract the opposite sex featuring as a central motivation for the worms. This emphasis changes in a more recent work, When I Arrived at the Castle (2019), which is a queer erotic horror story about a vampire hunter and the vampire whose castle she infiltrates. In an interview, Carroll describes this as a shift in the visibility of sexuality, sex, and romance in her work:

[A]t the back of my mind was the idea that, even though I’m gay myself and adore romance and sexual elements in the storytelling I consume, I have never explored it much in my own work. Part of it is that I’ve been shy, or at least a little insecure, in sharing that sort of vulnerability on the page. (Kenins 2019)

Our reading of her earlier work as queer Gothic, then, has more to do with its mining of the horror potential of cis- and heteronormativity: in TNP, Rebecca’s desire to feminise Bell’s gender presentation and her assumption that Bell either is or should be interested in boys, marrying a man, and having babies; in SOAM, the connection between Stacey’s fear of the inside of her own body and the fact that she has never been pregnant.

We will go on to discuss Carroll’s work as part of a long tradition of queer and feminist approaches to the Gothic. As Ardel Haefele-Thomas argues, ‘“Gothic” and “queer” are aligned in that they both transgress boundaries and occupy liminal spaces’ (2), while George Haggerty describes early Gothic fiction as a queer ‘testing ground,’ the ‘one semirespectable area of literary endeavour in which modes of sexual and social transgression were discursively addressed on a regular basis’ (2-3). Carroll’s particular approach to the body, though, is different from those found in much of the earlier queer and feminist Gothic tradition. In her work, the body becomes a source of horror that cannot be dealt with in the ways the Gothic has traditionally offered—whether rejection and casting-out or acceptance and redemption. Instead, she presents the horror of an experience of embodiment that has become unliveable, but that cannot be escaped.

Simultaneously, her stories work through skin to implicate the reader in these embodied experiences. How readers are positioned and imagined by her texts, as well as their positionality within society, shapes their interpretations, co-creations, and transformations of texts, in addition to their embodied responses. We explore Carroll as an heir to nineteenth-century sensation fiction, which aimed explicitly to stimulate physiological responses in its readers, as well as applying the film theory concept of body genres, visual spectacles of physical extremity that call forth mirroring responses in the viewer. The skins of Carroll’s readers become sites of interaction, porous, reactive boundaries that allow readers to experience the text both from the inside and the outside, visually, and tactilely. Her work calls forth sensory responses: skin crawls, pricks, sweats, and feels too tight, encouraged to do so through focalisation, use of colour, and constant depictions of uncanny skins, the call and response of horripilation.

Carroll, then, uses skin horror to imagine, and to make the reader embody, the perspective of a (usually non-normative and female) protagonist trapped in her own alienating and alienated skin. The fantastical, phantasmagorical elements of her work never allow for an imaginative resolution to this painful experience; instead, they become ways of exploring it and, within the discomfiting limits of the skin, staying with it.

The Predecessors of Contemporary Queer Feminist Gothic Horror

The recurring fascinations of Carroll’s work as queer feminist Gothic—experiences of gendered vulnerability, the body as both threatened and threatening—find their beginnings in eighteenth-century Gothic texts. These texts usually focused on passive damsel-in-distress protagonists, took place in menacing settings like mouldering castles, relied on ominous atmospheres, and employed melodramatic plots ending in marriage (Taylor 2006). While popular, the Gothic soon developed into two new subgenres, Gothic horror and sensation fiction, which were less interested in marriage plots and more interested in exploring the supernatural (Gothic horror) and sensation (sensation fiction).

Gothic horror, often considered to have started with Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), cemented the Gothic’s reputation as juvenile, not only because some of the most famous Gothic horror authors ‘were … adolescents, child prodigies really, when they wrote their most famous works’ (Kilgour 1995: 33), but also because female readers were regularly infantilised within cultural discourses at the time and readers of Gothic horror were ‘often described, if not by authors then by critics, as children or at best teenagers’ (Kilgour 1995: 33). Stories within this genre aim to ‘overwhelm our emotions and disturb normality with the shocking, taboo, and grotesque’ (Round 2020: 624).

Sensation fiction emerged mid-century and is strongly associated with the works of Wilkie Collins. This genre aimed explicitly to stimulate physiological responses in its readers, as well as emotional ones. As the name implies, sensation fiction was named for its intended bodily effects and ‘purported ability to create affect—specifically, suspense, shock, and fear—in readers’ (Kennedy 2009: 451; see also Daly 2004). This includes embodied response, ‘the physical effects of horripilation … in other words, making the flesh creep’ (Brundan 2006: 28–9).

This function is made possible because all these genres—the Gothic, Gothic horror, and sensation fiction—tended to be focalised through young female protagonists, who demonstrate readers’ expected physiological responses to the horrific stimuli in the texts, and they thus rely on narrative focalisation to provide scripted physiological and affective responses for readers (Miller 1986: 107–8). As Alison Winter (1998: 324) has argued, readers’ reactions are scripted in the texts as ‘sensation incidents’ intended to cause ‘a direct [readerly] physiological response.’ Because ‘the nervous system was seen as feminine’ and ‘women were thought to be more vulnerable to bodily and emotional feelings’ (Brundan 2006: 41), women continued to feature as protagonists and to function as the assumed readership of these novels, which often focused on the abnormality of women by centring ‘the figure of the mysterious (mad)woman’ (Brundan 2006: 3–4). Sensation fiction can thus be seen to present female protagonists and readers as Other while simultaneously aiming to appeal to a female readership. The fundamental tension of appealing to readers whom the texts Other would later become a central aspect of queer feminist Gothic horror.

Because of their association with juvenility, effeminacy, and embodied response, these genres increasingly became considered improper. Critics looked down on ‘the sensation novel [because it] was thought to conjure up a corporeal rather than a cerebral response in the reader’ (Daly 2004: 40). More, because of the assumed female readership, sensation novels were critiqued as too traumatising, too stimulating, and too addictive, with contemporary (and often male) critics condemning them as both immoral and harmful to young female readers (Brundan 2006: 38–40; see also Taylor 2006). Nonetheless, these genres only grew in popularity throughout the nineteenth century, helped along by innovations such as wood-pulp based paper, which allowed the production of cheap, popular magazines known as penny dreadfuls and affordable dime novels. As such, these genres and their later iterations came to be associated with the aptly named umbrella term pulp fiction, and thus, with the lower classes as well as women (see, e.g., Haefele-Thomas 2017). As Gothic-inspired forms and genres proliferated and grew ever more popular, the Gothic became ‘multiple and mutable … appear[ing] as affect, aesthetic, or practice’ (Round 2019: 8).

Reader Response: The Affective, the Physiological

The histories of Gothic genres make clear that readers’ expected responses to texts cannot be separated from the texts themselves. The particular aim of the genres stemming from the Gothic has long been to encourage specific embodied and affective responses—indeed, these responses are scripted in and through such texts. This paper must therefore also consider reader response criticism when deliberating readers’ scripted responses to texts and their and the texts’ cocreation of horrific imaginary worlds. Such a consideration inevitably includes both affective responses and physiological (embodied) responses, even while affective and embodied reactions to texts have not always been treated carefully in theoretical considerations of readers (both actual and implied) and texts. Moreover, this paper will discuss how readers’ positionality, including intersectional positionality, can shape their interpretations, cocreations, and transformations of texts.

Reader response criticism focusing on emotional responses to texts was, early on, deemed the ‘affective fallacy’ or the ‘confusion of the poem and its results (what it is and what it does)’ (Wimsatt & Beardsley 1949: 31). However, as Mailloux (1990: 40) argues, ‘[i]t was exactly this rhetorical topic—what a text does to a reader—that reader-response criticism came to take as its critical project’ in the late twentieth century, including ‘how a text’s rhetoric creates a temporal pattern of responses with puzzles, revelations, corrections, lessons, surprises, and a wealth of other effects often passed over by critical perspectives focusing on holistic meanings’ (Mailloux 1990: 48). Current critical considerations of texts therefore often focus on ‘how novels produce or reproduce affect in the reader’ (Kennedy 2009: 452).

Scholars agree that sensation fiction created the main template for how modern novels evoking embodied readerly responses work:

The genre offers us one of the first instances of modern literature to address itself primarily to the sympathetic nervous system, where it grounds its characteristic adrenalin effects: accelerated heart rate and respiration, increased blood pressure, the pallor resulting from vasoconstriction, etc. (Miller 1986: 107)

Kennedy (2009: 455) argues that sensation novels ‘narrate the body … in the constantly throbbing body of the text,’ while Daly (2004: 40) describes sensation novels’ ‘appeal to the nerves’ as a ‘veritable assault on the reader’s body.’ They achieve this by providing a depiction of the reader’s expected reaction within the novel itself, in and through the bodies of characters, as readers must be given ‘something to sympathise with’ as well as representations of expected physical responses (Miller 1986: 108).

Within visual media studies, Linda Williams’ concept of body genres offers a parallel to this theorisation of reader sensations. Building on Carol Clover’s work on physical audience responses to horror cinema, Williams (1991: 3) defines ‘body genres’—the three she examines are horror, melodrama, and pornography—as genres that not only evoke a physical response but specifically a response that imitates or mirrors what is happening on the screen. This response is semi-involuntary, ‘jerked’ from the audience in a kind of ‘uncontrollable convulsion or spasm’—tears in a melodrama, arousal, or orgasm in pornography, and in horror, anything from a mild frisson to a flinch, a scream, or an attempt to hide (1991: 5). Williams (1991: 5) cites James Twitchell’s observation that the root of the word ‘horror’ lies in what it does to the skin: the Latin horrere, ‘to bristle,’ as in horripilation or goosebumps. For Williams, viewers’ mirroring of the embodied affects they see on screen is itself gendered, since the ecstatic or tormented film bodies that evoke these responses are often those of women: ‘the bodies of women have tended to function, ever since the eighteenth-century origins of these genres in the Marquis de Sade, Gothic fiction, and the novels of Richardson, as both the moved and the moving’ (1991: 4).

As noted above, reader and/or viewer responses are scripted on the basis of an expected audience and are, in the case of sensation novels, carriers of ‘larger cultural allusions’ (Miller 1986: 108)—that is, they occur within a context. These contexts are deeply meaningful to both the scripting of responses and the actual responses themselves. We see this, for example, in the bodies of monsters, in what is represented as abnormal and therefore monstrous. Of course, different readers will respond to these cues in different ways; some may read resistantly, questioning or rejecting outright the depiction of certain bodies as monstrous, while others will accept the premises of the text with little resistance and few questions (Busse 2013).

This links, of course, to Rosenblatt’s (1994) consideration of reading as transactional in The Reader, the Text, the Poem. Here, Rosenblatt (1994) suggests that each reading experience is unique, and that readers’ interests, emotions, and experiences influence how each reader interprets a text. The sociopolitical contexts of a reader thus shape that reader’s interactions with and interpretations of a text, and as such, ability, age, class, gender, race, and other vectors of identification play a role in how a reader shapes a text, while writing within a genre is always a transactional and transformational process closely linked to sociopolitical change (e.g., Bakhtin 1986; Todorov 1976).

Within the genres that have developed out of the Gothic, then, there has been a shift in who and what is represented as monstrous, and this relies very much on the assumed readers of texts and the zeitgeist of the times: ‘It is not the inherent qualities of the being that make it monstrous but the response “we”—characters within the narrative and readers/viewers of these narratives—have to it that renders the creature a monster’ (Mittman and Hensel 2018: xi). For monster theorist Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (1996: 3, 5), we are able to deduce ‘cultures from the monsters they engender’ in narrative fictions and must examine them ‘within the intricate matrix of relations (social, cultural, and literary-historical) that generate them’ (Cohen 1996: 4).

Monstrous Bodies in the Gothic

Monstrosity is central to Gothic horror, and as Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s (1996: 7) classic description of the monster as ‘difference made flesh’ suggests, the monstrous tends to be an embodiment of something unacceptable: ‘the other, the “not us,” that which a culture rejects, disowns, disavows, or, to borrow from Julia Kristeva, “abjects”’ (Weinstock 2013: 275). In critical readings of Gothic horror, the monstrous often emerges as a powerful, if unpredictable counter-normative force. The fourth of Cohen’s (1996: 3) ‘breakable postulates’ in ‘Monster Culture’ positions the monster as a culturally constructed Other:

The monster is … an incorporation of the Outside, the Beyond—of all those loci that are rhetorically placed as distant and distinct but originate Within. Any kind of alterity can be inscribed across (constructed through) the monstrous body, but for the most part monstrous difference tends to be cultural, political, racial, economic, sexual. (Cohen 1996: 7)

Jack Halberstam’s (1995: 1) study of monsters as cultural objects, Skin Shows, argues that the monster ‘metaphorise[s] modern subjectivity as a balancing act between inside / outside, female / male, body / mind, native / foreign, proletarian / aristocrat.’ Again, this balancing act is culturally constructed: ‘the body that scares and appalls changes over time, as do the individual characteristics that add up to monstrosity, as do the preferred interpretations of that monstrosity’ (1995: 8).

Similarly changeable is the way Gothic texts respond to the transgressive power of the monstrous: in the words of Sharla Hutchinson and Rebecca A. Brown (2015: 9), monstrosity ‘produce[s] an ambivalence that often introduces both subversive fantasies about chaos and conservative desires to restore social order.’ The Gothic tends to enact a tension between an uneasy fascination with the monstrous body and the difference it represents, and the desire to cast out, reject, and abject it. In turn, queer and feminist approaches to the Gothic often seize on and reconceptualise these narratives, reclaiming the image of the Othered, monstered, non-normative body: ‘[T]he Gothic monster and the hybridity and body horror associated with the figure are also to the fore in contemporary queer Gothic fiction, [representing] the way in which society projects on to the homosexual and the transgender individual an image of monstrosity and the grotesque’ (Palmer 2016: 5). These approaches can take the form of direct addresses to and adaptations of earlier Gothic narratives, as in Susan Stryker’s (1994: 240-1) ‘Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamonix,’ which reclaims the word monstrous to describe herself as a trans woman:

I want to lay claim to the dark power of my monstrous identity without using it as a weapon against others or being wounded by it myself … I who have dwelt in a form unmatched with my desire, I whose flesh has become an assemblage of incongruous anatomical parts, I who achieve the similitude of a natural body only through an unnatural process, I offer you this warning: the Nature you bedevil me with is a lie.

Carroll’s skin work is certainly not a counterargument to this queer and feminist conceptualisation of the monstrous body, but it is different in emphasis and perspective. Where in Gothic horror the implied or explicit narrative perspective is often in some way normative and the monster is a cultural Other, Carroll’s work shifts these terms. Her work is almost always centred on women and girls, and often women and girls who in some way fall outside societal norms—who are disabled, gender-nonconforming, queer, or visibly agring. And even in its most horrific forms, the monstrosity they encounter is almost always a re-inscription of a norm, usually a gendered one. In her work on contemporary remixes of earlier Gothic texts, Megen de Bruin-Molé (2019: 3) describes this turn toward normative monstrosity as a trend in the contemporary Gothic, asking: ‘What does it mean that our historical monsters have moved from the margins to the mainstream? How can the monster, a figure that traditionally represents marginality, … become an emblem of the dominant ideology?’ But Carroll’s work does not just reverse these terms to tell more stories of our point of identification defeating the monstrous Other: the non-normative heroine, whom the audience identifies with and cheers for, defeating the normative monster, who we as readers have ourselves felt beset by. Carroll has almost no uncomplicated wins in her stories: the problems raised by the horrors of embodiment can neither be resolved through rejection nor through reclamation. These normative horrors can neither be escaped nor defeated.

YA Queer Feminist Gothic and Emily Carroll

Queer feminist Gothic horror comes out of two Gothic subgenres that emerged in the twentieth century and focused on Othered readerships, as well as Othered protagonists: the twentieth- and twenty-first-century Queer Gothic, and the feminist Gothic horror comics for girls produced in the 1970s. As discussed above, we can read traditional Gothic fiction as ‘a technology of subjectivity, one which produces the deviant subject opposite which the normal, the healthy, and the pure can be known’ (Halberstam 1995: 2). Feminist and queer reimaginings, however, subvert this paradigm, presenting the normative as monstrous. Haefele-Thomas (2017: 116-7) has argued, for example, that the ‘Queer American Gothic gives voice to people and stories often silenced by hegemonic cultural production’ and that queer Gothic texts upend ‘the stereotypes of the monstrous queer by making the normal … grotesque and contemptible.’ Likewise, feminist Gothic horror rejects and upends the traditional ways in which women are depicted as monstrous in comics ‘created by or aimed at traditionally male creators and audiences’ (Langsdale & Rae Coody 2020: 6). In comics created for or by men/boys, or even by women authors within a strictly patriarchal culture, they argue, women who break with normative femininity are regularly depicted as monstrous. In contrast, in feminist Gothic comics created by and for women/girls, normative femininity is itself depicted as monstrous. As Julia Round (2019: 12) argues, late twentieth-century Gothic comics for girls ‘focus on the problems of female experience … informed by transgression and transformation [and] characters are frequently handled subversively or sympathetically.’ Taylor (2008: 196) similarly argues that these comics, usually written for children by female authors, ‘follow in a tradition of subversive tales’ from the nineteenth century that ‘challenge patriarchal values by giving metaphorical expression to the extent of female confinement and oppression.’

Round (2019:10–11) defines the Gothic as an affective and structural paradox: simultaneously giving us too much information (the supernatural, the unreal) and too little (the hidden, unseen, unknown). It is built on confrontations between opposing ideals and contains and inner conflict characterised by ambivalence and uncertainty. It inverts, distorts, and obscures. It is transgressive and seductive.

She argues that the contradictory nature of the Gothic is compounded in feminist graphic Gothic texts because ‘comics are a contradictory medium [as] [t]he comics page itself combines the contrasting signs of word and image: the abstract and the representational’ (Round 2020: 624). In her book Gothic for Girls: Misty and British Comics (2020), she argues that girls’ comics ‘are the forgotten “herstory” of the medium,’ overshadowed by a focus on comics for boys and a cultural understanding of comics as masculine reading. Perhaps surprisingly, she states, comics for girls outsold comics for boys in mid-twentieth century Britain until comics sales fell in the 1970s, but the turn of the twentieth to the twenty-first century has seen a resurgence in the popularity of girls’ comics (Round 2020: 627–36). Throughout this time, Taylor (2008: 196) argues, ‘the female Gothic has differentiated into the domestic Gothic, the lesbian Gothic, and other forms’ which very often ‘rely on revisionist tales … and on the conventions of the Gothic in order to present subversive stories that empower [girl] child characters and readers.’

This increase in interest in girls’ comics has coincided with the late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century explosion of interest in horror texts for children (Reynolds 2006). Indeed, it is because of young audiences that multimodal horror narratives such as comics have gained popularity (Reynolds 2006). Reynolds (2006) argues that unlike most children’s literature, which focuses on outsiders and those with a sense of non-belonging, horror for children has tended ‘to instill a desire to belong to approved social groups, and advise readers how to behave in ways that will make them acceptable rather than monstrous.’ Late twentieth-century horror for children also often concludes with ‘what seemed dangerous and menacing … made safe’ (Reynolds 2006). In feminist texts for young readers, however, the opposite can be said to be true. Normative femininity is often made monstrous in these texts, mirroring the ways in which adolescents, specifically, were encouraged to identify with monsters in popular culture from the mid-twentieth century onwards as a reflection of new understanding of youth as rebellious and anti-normative (Austin 2022). This contrasts with more traditional views of women in comics (Langsdale & Rae Coody 2020: 6). Feminist Gothic comics, however, ‘exploit Gothic’s gendered and subversive qualities by offering open endings, inconclusive mysteries, and reframing Gothic motifs such as transformation and isolation’ (Round 2017: 10).

In Carroll’s work, this tendency is further developed and combined with queer concerns. Her work is characteristic of what we here term ‘queer feminist Gothic horror,’ which we consider to be an emerging subgenre of Gothic texts. Her comics regularly question normative beauty, popularity, heteronormativity, and normative conceptions of health, including ableism, through what they depict as monstrous. They also destabilise the separation of the monstrous Other and the self by frequently focusing on aspects of the self that are monstrous and inescapable. While, as Cohen (1996: 9, 14-15) has argued, fictional monsters have traditionally personified traits seen as ‘deviant,’ Carroll subverts these expectations, making monsters of those participating in heterosexist norms or who submit to normative expectations of feminine beauty and passivity, or by depicting the monstrous normative as an inexorable part of the ‘deviant’ protagonist herself. The assumed readership, then, are girls who, like Carroll herself, are liminal, whether queer, neurodivergent, disabled, or non-normative in their gender performances. As such, Carroll’s works reflect many of the uncertainties that young readers may feel regarding societal expectations, where they belong, who they are, and to whom they are attracted. Nonetheless, her monsters’ perspectives are also sometimes seen as potentially justifiable—in TNP, for example, we hear the monster’s explanation for its desire to take over Bell’s skin—or ambivalent, as when Stacey, the protagonist of SOAM, feels her skin has become, monstrously, separate from her ‘self’ but questions what this means for her identity and corporeality. As such, Carroll’s monsters break down the binary between the horrific and monstrous, the normative and the anti-normative, the self and the Other, and her work takes seriously Cohen’s (1996: 7) suggestion that ‘the monster resists any classification built on hierarchy or a merely binary opposition, demanding instead a “system” allowing polyphony, mixed response (difference in sameness, repulsion in attraction), and resistance to integration.’

The Monstrous (and the) Self in Carroll’s Queer Feminist Gothic Horror

TNP and SOAM both enact the desire to get out of one’s own skin, either by becoming fully alienated and disconnected from its experiences or by being literally removed or displaced from it by an internalised monster. In ‘When the Darkness Presses’ (2015), which acts as a prequel to SOAM, a secondary character, Stacey, describes a dream she had as a child where her arm disappeared: ‘my skin feels really hollow and cold … I looked up at my arm and it’s become this thin sheet of metal, wound in the SHAPE of an arm, and it starts unravelling.’ An older Stacey is the protagonist of SOAM, and here, again, she is haunted by the sense that what she has believed to be her own human body, both her skin and the flesh beneath it, might turn out to be something entirely different. The home parties she arranges to sell a line of skincare products, Alo-Glo, become the main site of the story’s skin horror. Giving a hand massage, she reflects to herself: ‘Of all the parts on a human body, I think hands are the most repulsive. / The knuckles / the nails / an alien species would think they were obscene.’ This defamiliarised, literally alienated perspective, which experiences the human body from the outside rather than from within, emerges again when she admits that she herself does not use Alo-Glo: ‘But not because it’s bad for you! / It’s far and away the most friendly, non-toxic beauty line on the market! / It’s just I get an allergic reaction. My skin puckers.’ For Stacey, the friendliness and goodness of a beauty product is unrelated to its actual effect on her own body; it is as if what her skin feels is unreal, or at least has nothing to do with her. Later, talking to a friend, she links this skin-numbness to the sense of not knowing whether she is dreaming or awake, whether she can trust her own senses. Characteristically, she ascribes these feelings to a hypothetical ‘someone,’ rather than to herself:

[I]t feels like they’re covered in these layers, these invisible layers, that muffle the world around them. / It doesn’t block things out entirely, just muddies it. Smears it a little. / But if it mutes their senses so much, how can you trust what does make it through? / It’s so easy for your body to lie to you.

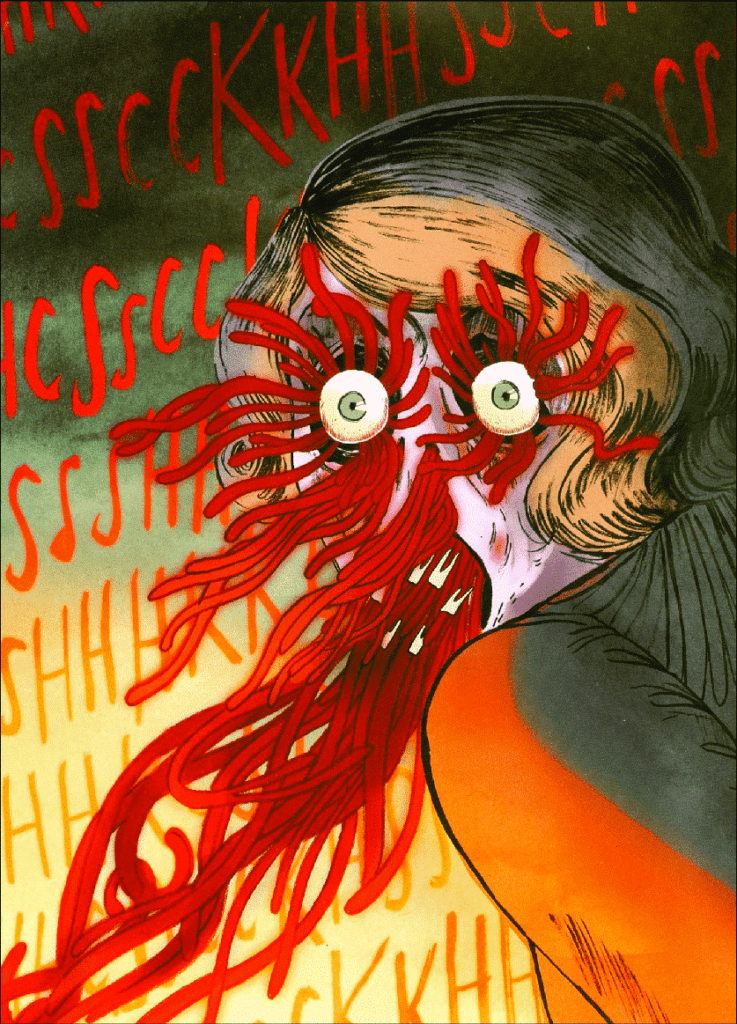

Stacey goes on to have repeated visions of melting skin: waking in the night, she finds what looks like a slumped, empty husk of skin floating in the kitchen; at another cosmetics party, she finds her fingers slipping through the skin of the woman she is massaging and begins to perceive the women around her as distorted, deliquescing masses of skin.

Figure 2: From ‘Some Other Animal’s Meat,’ reproduced with permission.

There is, of course, an implication throughout the story that the Alo-Glo could be the direct cause of all this; for instance, Stacey spills some lotion in the kitchen before the melting figure appears there. But this straightforward supernatural horror reading is not completely satisfying—partly because we know from the previous story that Stacey has had dreams of hollow, unravelling skin since childhood, but also because of the story’s continual interleaving of the spectacular visual wildness of Stacey’s skin visions with images of entirely mundane, gendered skin experiences. In one set of panels, Stacey examines her body in the mirror from different angles, with a kind of dispassionate assessment. In extreme close-ups, we see her flossing between her teeth, plucking nipple hair, examining her stretch marks, cellulite, the wrinkles under her eyes: routine feminine maintenance relating to appearance—beauty is, after all, skin deep. At a cosmetics party, she discusses her skin as if it is a separate, defective object that needs repair and mending: ‘it helps with just, you know, the texture of the skin – / – the wrinkles, the blotchiness.’ Stacey’s alienation from her skin is linked to, and only a half-step removed from, a gender-normative imaginary of the body in which the work of self-inspection and self-augmentation is internalised as, in Stacey’s words, a ‘treat.’ Normative beauty culture normalises a woman’s experience of her skin not from the inside, as a source of tactile sensation and connection to the physical world, but from the outside, as a visual display.

The story’s title comes from Stacey’s fear that ‘inside, I’m somehow the wrong stuff … What if my meat is some other animal’s meat / and the human part of me is just the skin / like the smooth layer of dough you drape over an uncooked pie?’ But it becomes increasingly clear that Stacey’s skin is not really ‘the human part’ of her either; she not only disconnects herself from her skin’s perceptions but imagines her skin as a potential traitor, passing on false sensory information: ‘It’s so easy for your body to lie to you.’ There is no way for Stacey to get rid of the ‘wrong stuff’ within her because she is wrong through and through; she has no foothold in her own body. While it is possible to read Stacey at the end of the story as having been replaced or taken over by the skin-monster, her dialogue suggests that she has just come to accept this state of self-alienation: ‘I’m happy now when I look in the mirror. I enjoy it. / I’m happy with The Person who looks back at me.’

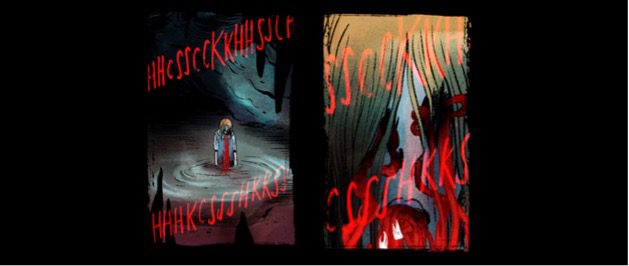

Figure 3: From ‘All Along the Wall,’ reproduced with permission.

.

The idea of a hidden presence beneath the surface of the skin emerges with even more visual drama in the webcomic ‘All Along the Wall’ and its print sequel, TNP (both 2014). In TNP, the protagonist, Bell, has come to stay with her brother and his fiancé, who we discover is Rebecca, the seemingly perfect yet worm-infested girl from ‘All Along the Wall,’ as an adult. As in ‘All Along the Wall,’ Rebecca, like her namesake in du Maurier’s 1938 classic, is an embodied reminder that the protagonist is performing femininity incorrectly. Her first appearance is a full-figure image that fills the whole page; she is elongated, slim, elegantly dressed, and from the seated Bell’s perspective she seems to loom over her. Her face is oddly flat, lacking in humanising detail; it will remain curiously unruffled throughout the story, even as her skin begins to rupture and what is underneath begins to emerge. As Miranda Corcoran (2020) points out, Rebecca’s skin is outlined in white ink rather than the black of the other characters (which is also the case in ‘All Along the Wall’); this gives the impression that she is faintly glowing—perhaps the glow of good skin care—but it also makes the borders of her body feel less distinct than others,’ visually foreshadowing how completely permeable and mutable these borders will turn out to be. (While the Carroll works we discuss here do not foreground racialisation as a dimension of potential embodied Otherness, Rebecca’s specifically white femininity, underscored by Carroll’s use of line colour, is also clearly significant here.) As in SOAM, an image of normative femininity—in this case a successful visual display of luminous skin, rather than the laborious process of perfecting it—immediately feels unsettling to the reader.

The reader and Bell’s immediate suspicion of this serene figure is quickly validated by more obvious horrors: she sees Rebecca’s teeth wiggling and clacking in her mouth as she eats, and a weird injury, like a bite from concentric, lamprey-like rings of teeth, appears on the housekeeper’s arm. Walking in the woods, Bell falls into an underground cave—the same one Rebecca fell into in ‘All Along the Wall’—and finds Rebecca there, cooing at something unseen in the water: ‘Are you looking forward to living with Mummy? / I’ve been getting your new home all ready for you.’ When she turns around, Bell sees bright red threadlike worms bursting and flaring from every orifice in her face. The worms in the pool, Rebecca explains later, are her babies, and she wants to give them a new home inside Bell’s skin.

Elisa O’Donnell (2020), writing about domestic hauntings in Carroll’s work, and Miranda Corcoran (2020), writing about the abject and Carroll’s use of bleeds in Through the Woods, both describe TNP as a story about the anxiety of the passage from girlhood to womanhood, centred on a teenager who, mourning the recent death of her mother, finds herself in this liminal stage without a guide. O’Donnell (2020) reads the narrative as a critique of ‘restrictive social and cultural conventions such as … how young women ought to handle themselves and their emotions socially, as well as how non-normative female bodies signify socially’ (18). Certainly, the heterosexual procreative imperative is made monstrous by this depiction of Rebecca and her ‘babies.’ This reflects the ‘herstory’ of the Gothic comic medium, in which normative femininity has long been depicted as monstrous (Round 2020), yet unlike in earlier Gothic comics for girls, in which the normative feminine is a monstrous Other separate from the self, the monstrosity of normative femininity is shown to be either an internalised part of the adult self or an inevitable futurity in Carroll’s queer feminist Gothic horror texts.

Bell deviates from these conventions in several ways; in Rebecca’s words she is ‘sullen and depressed’ (though we might just read her as grieving); compared to Rebecca she is shorter, stockier, with messier hair; she is physically disabled, as she wears a leg brace and often uses a cane. For Rebecca, all these differences from the ideal form she herself represents are something to fix, just as the young Rebecca fixes Lottie’s bow in ‘All Along the Wall.’ One of the story’s uncanny effects is that while the original Rebecca—once an ‘impossible’ little girl, we recall—seems completely supplanted by the monstrous worm-creature, who has both perfected and polished her outside and replaced her insides, the worm-creature itself is far from alien. It speaks in the voice of Bell’s social world and echoes its values, encouraging her to dress more femininely, to brush her hair, to allow herself to be ‘cured’ of her physical disability and depression, to (in an unusual way, but nonetheless) settle down, establishing a heteronormative nuclear family with children. Having had her offer of new clothes and make-up rebuffed, Rebecca presents the prospect of being invaded by her ‘babies’ as a chance for a complete makeover, a ‘cheerful change’ into a gender-normative, ableist ideal: Bell’s leg will be fixed, her body will be stretched into ‘something tall, slim, and pretty,’ she will, outwardly, seem happy. The idea that someone might not wish to inhabit such an idealised body and live so ‘perfectly’ is as incomprehensible to Rebecca as it is to society more widely.

TNP, then, is a horror story about female embodiment and growing into a heteronormative and ableist adulthood, as SOAM is a horror story about female embodiment and ageing. In both cases the protagonists are offered an escape from the anxiety of embodiment. At the end of SOAM, Stacey finds herself able to use Alo-Glo on her skin—she was just ‘overreacting’ before, she decides—and is happy to see ‘the Person’ who looks back at her from the mirror. Stacey’s anxiety, both visual and tactile, is alleviated; she has stopped feeling her skin’s reactions, and whoever might be in the mirror now seems visually acceptable. Rebecca, in the monstrous voice of normative injunction, offers Bell the same bargain: she can get rid of the horror attendant on having a body by giving up the connection between her body and her self, giving up her place in her own skin. This is, of course, a kind of death, but as Rebecca points out, Bell is already socially dead. Wouldn’t she prefer to be the belle of the ball, popular and perfect?

The disarraying of the border between life and death and the fear that comes with it—a live being that is somehow deathlike, a dead being that behaves as though it is alive—is, obviously, central to Gothic horror. In Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva (1982: 4) describes the way living in a human body is a continual process of abjection, until finally the body itself becomes abject in death: ‘Such wastes drop so that I might live, until, from loss to loss, nothing remains in me and my entire body falls beyond the limit—cadere, cadaver … [I]t is no longer I who expel, “I” is expelled.’ But in Carroll’s work, this process of ‘fall[ing] beyond the limit’ becomes disrupted; a body may become abject through monstrous transformation, decay, or death, yet any attempt to free oneself from this process is always ultimately unsuccessful. Feminine normativity is inescapable.

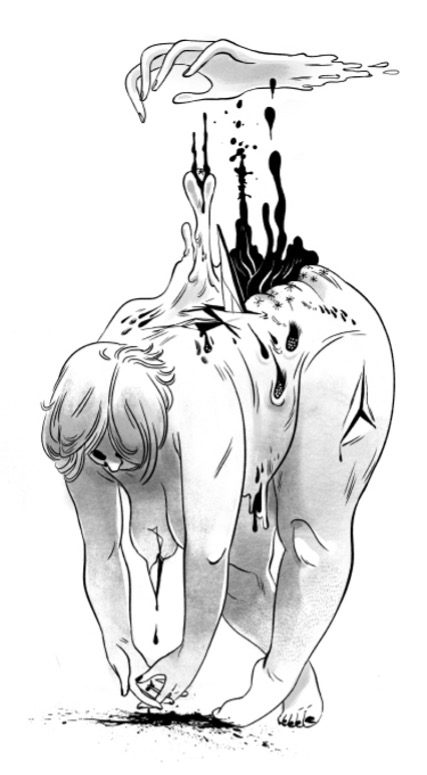

Figure 4: The splash from Carroll’s webpage, reproduced with permission.

On the splash page of Carroll’s website, a woman’s body, maybe dead, maybe alive, hangs in the air. Her eyes are black and empty; the skin of her back is melted or torn; a foot with painted toenails brushes the floor to leave a trail of blood. A disembodied hand hovers above the body; it looks as though the body has only just loosed from its grip. Yet the body does not seem to be falling; it is just floating there, static. The image is perfectly ambiguous: the body is both discarded and retained; it tears away and stays in place. Here the process of abjection has been arrested, frozen: someone has tried to drop, lose, or rid themselves of this wounded, deathlike form, but somehow it isn’t going anywhere.

Carroll’s skin work, then, imagines female embodiment as a source of fear, disgust, and abjection that cannot be fully coped with through either of the modes that Gothic horror tends to offer: it can neither be rejected and cast out as the Other nor reclaimed and embraced as part of one’s own self-making. In both these stories, the monstrous agents of the feminine norm, the skin-lotion-creature in SOAM and the thread-creature in TNP, not only contribute to creating the desire to escape one’s own skin but seem to offer a way of doing so—at a cost, of course. Yet whether you accept (willingly or not) this bargain, as Stacey does, or reject it, as Bell does, it does not seem to work. Bell, having apparently defeated and escaped the thread-creature, finds it sitting beside her (in her brother’s body) as she tries to flee. Stacey seems almost, but not quite, successfully subsumed by the skin-lotion-creature, delivering a wavering, uncertain sales pitch for her self-alienation: ‘it’s REALLY not a big deal! / it’s not a big deal. / I’m just / I’m happy now when I look in the mirror. I enjoy it. / I’m happy with the Person who looks back at me.’ In Carroll’s skin horror, there is no way to win by transcending, defeating, escaping, or even surrendering to the source of fear: you are stuck in your body, and you cannot get rid of your own skin, but you might be able to get rid of who you are now by giving in to the monstrous.

Moreover, Carroll’s comics not only represent but enact this particular experience of embodied horror on and in the reader’s own skin. As our discussion of sensation fiction and body genres shows, the physical response of the reader or audience is a long-established aspect of horror. What is striking, then, about these comics’ involvement of the reader’s body is not so much that they do it, but how they do it—how Carroll’s art involves the reader physically in the way she specifically engages with skin and embodiment. Carroll’s work is full of moments where the reader, through a scroll, a click, or the turn of a page, is confronted by a visual shock—what we could call a jump-scare in still-image form. This image is almost always of a body, often though not always a face, in which something unexpected is happening to the skin. We might think of the scroll-down to the dripping, eyeball-filled red visage in the mirror in room 1002 in ‘The Worthington’ and to the corpse-faces in ‘The Three Snake Leaves,’ or the click-through in ‘The Prince and the Sea,’ which reveals first the beautiful prince’s drowning, then a time-passing image of his body face down in the water, then the mermaid raising his head to reveal his corpse’s water-warped face. SOAM has a number of these moments, most distinctly in the panel when Stacey looks up from a hand massage to see her friend’s face melting. Perhaps the paradigmatic example, though, is Bell’s confrontation with Rebecca in the cave, where a turn of the page reveals a full-page spread of the red worms bursting through the smooth, rosy surfaces of Rebecca’s face.

Significantly, each of these visual shocks is paced in the same way: an initial shock followed by an almost immediate return to the shocking image. The very short ‘Room 1002’ is a simple example of this: the two panels showing the protagonist’s reflection in the mirror are aligned horizontally next to each other, so reading left to right we see the reflection (warped, dripping blood, so many eyeballs) and then immediately get a second look (twisting, wounds opening, are those things mouths?). In ‘The Prince and the Sea,’ the first glimpse of the prince’s face after drowning is followed by a long scroll-down to the bottom of the sea as the mermaid takes her lover home, during which the face appears four more times through the dark. The initial physical flinch is not followed by a release of tension, another building of suspense, or an immediate transition into action or violence; instead, the shocking image keeps coming back, so that the initial shock, rather than fading or being given an outlet, turns into a ratcheting, inescapable sense of horror. This drawing out plays itself out on the reader’s skin: the goosebumps and flush of our initial shock lengthen uncomfortably and spread, causing our flesh to creep and crawl, our temperature to vacillate between hot and cold, mimicking the carefully chosen colours of Carroll’s artwork, her strong reds and chilly blues, and we sweat so our skin prickles, tightens, and begins to feel foreign and unruly.

In TNP, the worm-face reveal compounds this mirroring of physical response through its use of perspective. TNP is narrated in the third person, and the visual focalisation tends to follow Bell from an intimate outside perspective, with frequent close-ups on her facial reactions. In moments of heightened fear, though, we see through her eyes, a form of free-indirect discourse: in the panel where we first see Rebecca, we are in Bell’s lower perspective on the sofa, and when Bell notices Rebecca’s teeth clacking as they eat, we see the dialogue fade out as Bell stops paying attention, then a close-up on Rebecca’s mouth as Bell focuses on it. In the worm-face reveal, this shared visual perspective turns into physical sympathy: the reader flinches at the face reveal at the same time as Bell, then takes in Bell’s reaction, seeing their shock mirrored on her face, before the perspective again returns to Rebecca to show that the worm-face is still there. Bell’s face, when we see it, demonstrates how our own blood ought first to flush our cheeks in horrible anticipation, then rush away after the reveal, leaving us pasty, sweaty, and shaky. Carroll uses the body genre’s mirroring of physical response to create an experience of skin horror that is both outside and inside, visual and tactile—we are looking at the horror from the outside, but also feeling it from the inside.

Conclusions

Most feminist Gothic comics aim to successfully subvert patriarchal norms (Round 2019, 2020; Taylor 2008). In contrast, while Carroll’s queer feminist Gothic horror comics allow the reader to take the perspective of a non-normative protagonist beset by a monstrous norm, we experience no cathartic victory or liberation, only a concrete, physical reminder of the vulnerable and constricting boundaries of our own skins and contexts. Carroll’s graphic texts do question normative ideals of beauty, health, and heteronormativity, yet they also question the split between the monstrous Other and the self by centring monstrous yet seemingly inescapable ways of being, depicted as luridly inevitable. The monstrosity of normative femininity is an unyielding part of female lives.

The assumed readership, ‘deviant’ and liminal girls, whether queer, neurodivergent, disabled, or gender non-normative, feel disgust, fear, and abjection as they interact with her works, which are carefully crafted to elicit such affective responses along with their embodied reactions, such as horripilation. Carroll’s works reflect these uncertain young readers’ rejection of societal expectations while nonetheless emphasising that all women are subject to norms of femininity and that these norms will inevitably affect us all. Her monsters, whether they represent an inescapable future, as in TNP, or an ingrained present, as in SOAM, are depicted as justified in their desires or even ambivalent. Through this, Carroll’s monsters dissolve the binary between the monstrous normative and reader/protagonist. Her work thus represents a new approach and new genre.

REFERENCES

Austin, Sara (2022), Monstrous Youth: Transgressing the Boundaries of Childhood in the United States, Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail (1986), ‘Speech Genres’ and Other Late Essays, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bruin-Molé, Megen de (2019), Gothic Remixed: Monster Mashups and Frankenfictions in 21st-Century Culture, London: Bloomsbury.

Brundan, Katherine (2006), Mysterious Women: Memory, Madness, and Trauma in the Nineteenth-Century Sensation Narrative, PhD diss., University of Oregon.

Burdge, Anthony S. (2006), ‘Ghost Stories,’ in Jack Zipes (ed.), Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 138-139.

Busse, Kristina (2013), ‘The Return of the Author: Ethos and Identity Politics,’ in Jonathan Grey & Derek Johnson (eds.), A Companion to Media Authorship, Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 48-68.

Carroll, Emily (2013), ‘Out of Skin,’ Em Carroll http://www.emcarroll.com/comics/skin/, (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Carroll, Emily (2013), ‘The Three Snake Leaves,’ Em Carroll http://emcarroll.com/comics/snakeleaves/, (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Carroll, Emily (2014), ‘All Along the Wall,’ Em Carroll, http://emcarroll.com/comics/wall/, (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Carroll, Emily (2014), ‘The Nesting Place,’ in Through the Woods, London: Faber and Faber, n.p.

Carroll, Emily (2014), ‘The Prince and the Sea,’ Em Carroll, http://emcarroll.com/comics/prince/andthesea.html, (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Carroll, Emily (2016), ‘Some Other Animals’ Meat,’ Em Carroll, http://www.emcarroll.com/comics/meat/, (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Carroll, Emily (2018), ‘The Worthington,’ Em Carroll, http://www.emcarroll.com/comics/worthington/, (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Carroll, Emily (2019). ‘Discussing Body Horror and Inspiring Women with Emily Carroll.’ Toronto International Festival of Authors, 4 Mar. 2019. festivalofauthors.ca/2019/blog/discussing-body-horror-and-inspiring-women-with-emily-carroll. Quoted in Christina Dokou (2020), ‘From Hand-hold to Haunt-held: “Lesbian Continuum” meets “Infection in the Sentence” in Emily Carroll’s Comics,’ Ex-Centric Narratives: Journal of Anglophone Literature, Culture and Media, No. 4.

Clover, Carol (1987), ‘Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film,’ Representations, No. 20, pp. 187–228.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome (1996), ‘Monster Culture: Seven Theses,’ in Monster Theory: Reading Culture, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Corcoran, Miranda (2020), ‘Bleeding Panels, Leaking Forms: Reading the Abject in Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods (2014),’ The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, Vol. 10, No.1.

Daly, Nicholas. 2004, ‘Sensation Fiction and the Modernisation of the Senses,’ in Literature, Technology, and Modernity, 1860–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 34-55.

Haefele-Thomas, Ardele (2017), ‘Queer American Gothic,’ in Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock (ed.), The Cambridge Compantion to American Gothic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 115-127.

Halberstam, J[ack] (1995), Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters, Durham: Duke University Press.

Hutchinson, Sharla & Rebecca A. Brown (eds.) (2015), Monsters and Monstrosity from the Fin de Siecle to the Millennium: New Essays, Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Kenins, Laura (2019), ‘Creative Intuition Led Emily Carroll to her Erotic Graphic Novel about a Would-be vampire Hunter,’ Quill & Quire, 6 May 2019, https://quillandquire.com/omni/creative-intuition-lead-emily-carroll-to-her-erotic-graphic-novel-about-a-would-be-vampire-hunter// (last accessed 9 September 2022).

Kennedy, Meegan (2009), ‘Some Body’s Story: The Novel as Instrument,’ NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 451-459.

Kilgour, Maggie (1995), The Rise of the Gothic Novel, London: Routledge.

Kristeva, Julia (1982), Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon Roudiez, New York: University of Columbia Press.

Langsdale, Samantha & Elisabeth Rae Coody (2020), ‘Introduction,’ in Samantha Langsdale & Elisabeth Rae Coody (eds.), Monstrous Women in Comics, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 3–14.

Mailloux, Steven (1990), ‘The Turns of Reader-Response Criticism,’ in Charles Morana dn Elisabeth F. Penfield (eds.), Contemporary Critical Theory and the Teaching of Literature, Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, pp. 38-54.

Miller, D. A. (1986), ‘Cage Aux Folles: Sensation and Gender in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White,‘ Representations, No. 14, pp. 197-136.

Mittman, Asa Simon and Marcus Hensel (2018), “Introduction: A Marvel of Monsters”, in Primary Sources on Monsters, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

O’Donnell, Elisa (2020), ‘Hauntings of Bodies, Selves, and Houses: A Comparative Reading of Three of Emily Carroll’s Short Horror Comic Stories,’ Digital Literature Review, Vol. 7.

Palmer, Paulina (2016), Queering Contemporary Gothic Narrative 1970-2012. London: Palgrave.

Reynolds, Kimberley (2006), ‘Horror Stories,’ in Jack Zipes (ed.), Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 256.

Rosenblatt, Louise M. (1994), The Reader, the Text, the Poem, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Round, Julia (2017), ‘Misty, Spellbound and the Lost Gothic and British Girls’ Comics,’ Palgrave Communications, No. 3, n.p.

Round, Julia (2019), Gothic for Girls: Misty and British Comics, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Round, Julia (2020), ‘Horror Hosts in British Girls’ Comics,’ in Clive Bloom (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of the Contemporary Gothic, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 623-242.

Stryker, Susan (1994), ‘My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamonix: Performing Transgender Rage,’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 237-254.

Taylor, Beverly (2006), ‘Gothic Fiction,’ in Christine Alexander and Margaret Smith (eds.), Oxford Companion to the Brontës, Oxford: Oxford University Press. PDF.

Taylor, Laurie N. (2008), ‘Making Nightmares into New Fairytales: Goth Comics as Children’s Literature,’ in Anna Jackson, Karen Coats, and Roderick McGillis (eds.), The Gothic in Children’s Literature: Haunting the Borders, London: Routledge, pp. 195-208.

Todorov, Tzvetan (1976). ‘The Origin of Genres,’ New Literary History, Vol. 1, No. 8, pp. 159–170.

Weinstock, Jeffrey A. (2013) “Invisible Monsters: Vision, Horror, and Contemporary Culture”, in The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, London: Ashgate.

Williams, Linda (1991), ‘Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess,’ Film Quarterly Vol. 44, No. 4 (Summer, 1991), pp. 2-13.

Wimsatt, W. K., and M. C. Beardsley (1949), ‘The Affective Fallacy,’ The Sewanee Review, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 31-55.

Winter, Alison (2009), Mesmerised: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey