Finding the Artist: The Role of the Feminist Detective

by: Teresa Forde , October 5, 2020

by: Teresa Forde , October 5, 2020

Marion Adnams was an artist who produced a sustained output of paintings, drawings and etchings throughout the twentieth century, whilst also working as an art teacher and lecturer. In embarking on co-curating an exhibition of Adnams’ work, we needed to find out about this mysterious artist, some of whose work was held in a number of UK galleries but about whom little was known. Finding out about an artist and their body of work can be a veritable task of detection and discovery. The role of the detective is to find out information, ask questions and solve a crime or mystery: yet the process of detection also raises issues about which questions should be asked, as well as the context and implications of any detection. What could the crime be in the context of Marion Adnams? How is such a mystery solved? Clearly, there is the question of why Adnams’ work has not remained prominent and recognised within British art history, and the question of how to solve this issue. Equally, there are the questions of how the artist managed to continue producing work, and the ways in which her work can be recuperated in terms of British art history within a feminist project.

In her account of Carolyn G. Heilbrun’s Writing a Woman’s Life (1988), which explores the female detective, Kimberly Maslin recognises the attempt to provide more varied narratives for feminist detectives, which has contributed to reinventing the genre, ‘an important development for feminism because of her life choices, her relationship to the canon, and the social issues that receive attention’ (Maslin 2016: 65). Unlike the traditional detective figure, the function of this feminist detective is ‘to construct alternative narratives for women and to craft narratives that allow the isolation and marginalization of women to emerge as offenses against society’ (Maslin 2016: 66). The offence of exclusion and marginalisation of Adnams’ work provides a useful starting point, and encapsulates the work of the feminist detective in re-investigating the context of this artwork and the artist herself. Constructing a narrative of events and investigating the lack of representation and loss of knowledge of Adnams became the focus of a project I undertook with the aim of engaging with her work. This project involved constructing a model and making a video, which I began at an early stage to get a sense of my relationship to both Adnams and her work.

In terms of the function of feminist investigation, it is clear to Maslin that ‘women’s invisibility persists’ yet the construction of a narrative or an interpretation can create its own problems: ‘[t]he temptation to abandon one’s own achievement narrative in favor of a romantic plot remains; the challenge of pursuing one’s own achievement narrative in the midst of familial demands endures’ (Maslin 2016: 71). Therefore, detail and evidence become significant in understanding what has happened in the past, yet also the need for both the past and present to be carefully contextualised. Adnams’ particular situation includes her family responsibility in caring for her mother, and later issues with her eyesight. There are also particular issues that emerge from her dual roles as an art teacher and an artist. Although such clues are addressed, the interpretation, or a solution, require flexibility and space for others to interpret meaning, in addition to the detective.

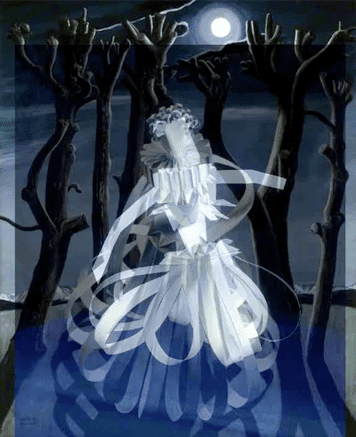

At the start of the project, we did not even have a photograph of the artist but, with the help of her Estate, we uncovered a range of paintings and biographical detail. We also managed to talk to people who knew her, which gave us additional insight. One of the earliest paintings that I had seen, Infante égarée (1944), intrigued me greatly and seemed to capture a sense of my relationship to Adnams. Further, it to me became representative of her identity, that of a woman lost in the woods who is being sought out and investigated. This relationship to Infante égarée, which depicts a card model of a woman standing in the woods at night, led to my experiment of constructing a card model of my own, based on the painted figure, to see how it would function, as I wanted to explore the conditions of its construction. As we discovered, Adnams made card models and then painted them into her artwork, so it seemed appropriate to explore her work by attempting to re-enact it. The act of making the model enabled a creative process of exploring evidence and clues to her work. I learned a lot about her work through this, process and also discovered a lot about my own interest in it. The process of detection became one of physically handling materials via assembly, to see how and if they could function.

In order to undertake detective work, there is also the need to consider how the findings are interpreted. As Marsha Meskimmon recognises,

women’s art does not materialise the essence of woman or presuppose an a priori subject which only needs to find a voice through which to emerge. Rather, I am arguing that the particular conjunction of ‘woman and art’ is contingent and that female subjectivity is bodied forth by these diverse interactions with visual and material culture across varied historical circumstances (2003: 72).

Therefore the ‘voice’ is not merely rediscovered, but constructed in the process of its detection and analysis, and it is within this process that such interactions are key. Detection also reflects Adnams’ own process of taking objects from the world and placing them into a different, surrealist context. By doing so, the object comes to be placed out of context or seen anew, and this process of discovery becomes a key component of Adnams’creative practice. By responding to and interacting with Adnams’ work, I am enacting a creative process which engages with this process. As Kathryn Oliver Mills argues, ‘In order to solve the mystery, the detective, too, must see the significance of things which are often very ordinary’ (Mills 2007: 179). So Adnams’ practice also reflects the work of a detective, noticing what is often overlooked and, further, challenging traditional perspectives, not to answer questions but rather to pose them. In investigating the painting Infante égarée, the sense of the ordinary was very far from my mind, as the piece encapsulates a surrealist scenario full of mystery and intrigue. In addition, Adnams encouraged an openness of meaning in her own work in line with surrealist poetics. It seemed as though the card model in the painting Infante égarée could be reconstructed, and the act of constructing this figure became part of the process of investigation. The card model consisted of a still figure in the landscape but, when put in context and animated for the video, it becomes something else. For me, it becomes an articulation of the artist herself, representative of Marion Adnams as the most tangible version of the artist that I could detect at the time.

Investigating Infante égarée, involved negotiating the way that the figure in the forest within the artwork provided for me a ‘version’ of the artist, and a focal point to explore her identity. Adnams has already been described as a surrealist in previous coverage of her work exhibited in the 1940s through to the 1970s, and there is a clear sense of this perspective in her work. Adnams wrote in an account of her work that the figure in Infante egaree is ‘aimlessly wandering’ (Adnams 16/8/1944/), yet rather than being lost or disoriented, the model seems almost purposeful, or at least as though this is a transient period of disorientation that will pass. Painted in 1944, there is a sense that the artist herself may have felt lost and frustrated, undertaking working as a teacher during the war and trying to continue her creative practice. This situation is expressed with a sense of isolation and a disheartened tone: ‘after that the lights went out and the doors closed. I knew the frustration and privation of the war years without any of the excitement’ as she expresses in her writing (Adnams undated: 9).

After making the model, I then superimposed the animated figure onto the original Infante égarée painting as a form of palimpsest, altering the model with the traces of the original, and providing a backdrop to the piece. This process of superimposition blended the two models, merged my research with Adnams’ painting, and provided a commentary on what I had learned about her work. As we discovered, in producing the work Adnams had been inspired by the music of Ravel, so the necessity for the act of animation made more sense. The title of the original painting had been restored to the preferred French version, which had been denied on initial exhibition at Manchester, where it was translated as The Distraught Infanta. The video project reflects the artist’s preference for a French title, whilst including a translation as well: the video installation was entitled ‘Découverte de l’artiste (discovering the artist): Finding Marion Adnams through her work with a focus on Infante égarée’. The video installation formed part of the exhibition Marion Adnams: A Singular Woman at Derby Museum in 2017/18. I collaborated with Des O’Brien, who contributed a soundtrack for the video installation which played throughout the exhibition. The music emanated from the video, yet enveloped the whole gallery space and created an ambiance which demarcated this as a different, significant place to engage with the work.

The process of palimpsest was chosen for the video installation where the original painting is still traceable, and this structure tracks the process of discovery. The detective aims to see things differently and make connections in order to assemble the clues. Equally, this assemblage is enacted as much to discover as to solve. The video installation has been designed to illustrate an engagement with Infante égarée, and to discover something about the artistic practice, although it does not solve the mystery of the painting itself or Adnams’ status. Instead it provides a context in which to explore them. Equally, the detective can also understand their own position through the process of assemblage and, in this process, ‘one’s sense of individual autonomy gives way to a reality of immersed interdependence, in which it is relationship that constructs the self’ (Gergen 1991: 147). The ‘mystery’, ‘crime’ or ‘puzzle’ being investigated here is the artist’s lack of prominence, despite having early recognition for her work. This lack of later recognition has to be understood in terms of both her work and life. The detective researches clues, including artworks, in order to understand the artistic practice and its context, if not to directly fix the meaning of the work itself. Adnams’ personal correspondence expresses her frustration at her inability to directly respond to the war in her work, about which she is reassured by Lawrence Haward of the Manchester Art Gallery (Hayward 1943). However, it could be argued that Marion does respond to her experiences, albeit in an indirect manner. As Marilyn Rose recognises in detective strategies:

In the tension, for example, between the absent narrative, the mystery surrounding a crime, and the investigative narrative, with its emphasis on assembling clues and solving a conundrum, the detective story exhibits a capacity for self-reflexivity or meta-literariness that draws attention to the reading process itself and its underlying epistemological desires (2014: 205).

As a response to the painting, the video seeks to reanimate the artist and to reinsert her into art history. This is the role of the detective, to solve the crime and reveal the mystery of my relationship to the artist, as well as elucidating the reasons for her exclusion. Such exclusion is not uncommon in terms of women’s marginalisation within art history, and the construction of patriarchal narratives which work to exclude as well as include. There is also a challenge in considering one artist’s life and work without recognising the wider context. For Adnams, the longevity of a profile for her artistic practice was further affected by not being part of a wider movement, both negatively, in terms of a lack of recognition of her work within the context of surrealism, and positively, in not being constrained by the boundaries of such a movement. However, the singular nature of the work does not imply a lack of knowledge or engagement with other artwork, but requires different ways of understanding the resonance of her art, which was necessary to consider in relation to surrealism and other practices.

Adnams’ work was often discussed in terms of surrealism, but remained on the margins of this movement—although she did exhibit amongst a range of modernist artists, such as Henry Moore and Eileen Agar earlier in her career. The investigation into Adnams as an artist, and her relationship to wider art history, was revealed as a hidden history which we encountered and needed to name and identify. In addition, the issue of why she was not more prominent in contemporary art became the focus of the investigation, while deconstructing the act of detection in the process. The issues to investigate involve the construction of British art history and practices of exclusion and definition. Where can Adnams be placed, and what is her relevance? These issues are culturally coded. The approach to investigating the act of exclusion is reminiscent of Sally Potter’s reworking in Thriller (1979), based on the story of Mimi in Puccini’s La Boheme. As Potter explains in an interview with Scott Macdonald:

rather than lament Mimi’s death, the questions becomes why did she have to die at the end of the opera. Mimi searches for clues to explain why she is excluded from the narrative. As Potter explains, ‘Just as Mimi is the detective looking into her own death, I felt as if I were a detective looking into the meaning of this work I was trying to construct (Potter in MacDonald 1998: 408).

I am reflecting on the questions about exclusion from a narrative, as well as interrogating my role in detection through engaging with the painting. Yet there is also the question of what that narrative itself entails. There has been an ongoing interest in the detective as a feminist trope, because it explores issues of identity and questions the narrative. This investigation considers the issue of exclusion from the canon, and reinstatement into it in order for the role of the detective to be the solution of a mystery via the completion of a puzzle. Yet, perhaps there are also other ways of addressing this patriarchal ‘crime’. In terms of Sally Potter’s Thriller, Lucy Bolton argues in a consideration of Joan Copjec’s work on the film that the character of Mimi, ‘is included in order to be excluded, to sustain Rodolfo’s power’ (Bolton 2015) This phrasing highlights the ways in which privileging and prioritising of some artists becomes intrinsic to the exclusion of others in a relationship of power and prominence. Mimi actively, and violently, is written out of the narrative. In removing Mimi, the power of Rodolfo is reinforced and sustained. However, in Potter’s version, Mimi asks why she has been removed, edited out the narrative and excluded. The detective asks these questions about Adnams, and the investigation is very much embedded in the need to reinforce particular narratives and strategies of power. For many surrealist women, surrealism also had to be negotiated, and inclusion in such a seemingly-challenging art movement was often fraught with negotiation of power and patriarchal influence.

In order to maintain exclusive power, there is a need to exclude. This approach is articulated by Penelope Rosemont in her account of surrealist women artists, as she argues that women surrealists are seen to emulate conventional practices and therefore to become anathema to surrealist aims:

Certain critics and curators have attempted to isolate women surrealists from the Surrealist Movement as a whole, not only by reducing their work to the traditional aesthetic frameworks that surrealists have always resisted but worse yet by relegating them to a subbasement of the art world known as ‘Women’s Art’ (Rosemont 2001: xxx).

Marion Adnams was not part of a surrealist movement, although her work has been described as such. She has now been recognised as a part of British surrealism and British art alongside other British women artists, in recent exhibitions in London and Leeds. Somewhat ironically, the work of women artists in the Dulwich British Surrealism exhibition has become popular and well-received, as it establishes a challenge to the status quo and convention, whilst offering alternative responses to the surrealist movement. In these terms, ‘Women’s Art’ becomes a celebratory concept, although the longevity of this focus and the ongoing visibility of such work is still in question.

As well as her definition as a teacher and an artist, Adnams could also be described as a spinster—somewhat problematically, due to the traditionally negative connotations of not having married, and remaining a ‘single’ woman. Additionally, making sense of the artist in contemporary terms for my own work, and within the historical context reveals the extent to which her work is still very relevant and challenges the status quo. So the detective work in revisiting her painting reconstitutes Adnams as someone whose character and work is vivid and relevant. Irons recognises that the depiction of the detective can change: ‘For while the old spinster has in effect become a young hipster, many of the attitudes that surrounded the spinster remain’ (1995: 65). The spinster is more of a challenge ‘in her existence outside the normal society of heterosexual couples—than in the repression which the term often implies’ (I65). In undertaking the case of Adnams, such definitions become reflected in exploring the artist’s identity.

Adnams’ persona provides the possibility of the definition of the hipster, seemingly more relevant to a contemporary context. Yet how do these two seemingly dichotomous definitions of spinster and hipster co-exist? And how do these relate to her work? Rather than see the spinster as a problematic portrayal, Irons argues that experience and perspective, aligned with an older person, are clearly important qualities to celebrate (although it should be recognised that, historically, the term ‘spinster’ had been used to describe all women who were not married at the age of consent). This conundrum is partly articulated in the desire to contextualise Adnams both within an artistic tradition, and within contemporary art practices. In considering Adnams, the dichotomy between the historical identity, little known at the time of constructing the video piece, and interaction with the painting, establishes a more fluid identity for the artist. As such, the discovery of her wider exclusion from a more prominent position in art history, and the act of establishing her identity also becomes a work of uncovering and questioning existing definitions.

Adnams was also someone whose work resonated with surrealist art in Britain, and who was regarded as a modern artist in the mid-twentieth century but became less well known later. As recognised, she worked outside of the specifically surrealist groups, although she did later join the Midland Group of Artists, which also included the artist Evelyn Gibbs. Although my analysis is a feminist one, it emerges within some material regarding the ‘post-feminist’ role of the detective. In exploring depictions of the feminist detective, and the consideration of their lives and work, there is a sense that sharing and interacting experiences is a foundational element of post/feminist positioning. As Nete Schmidt argues:

‘the power to attract and be objects of identification is predicated on the possibility of constructing a collective politics and criticism using the singular female/feminist identity as common ground’ (2015: 445).

So, in Schmidt’s terms, my investigation, focusing as it does on one woman’s work, would seem to provide a conduit from which to investigate wider issues of feminism. However, it is important to recognise a context rather than just accept Schmidt’s post-feminist perspective, because none of this practice exists in isolation and, as has been recognised, there are significant implications for an artist’s own work. The interaction with Infante égarée offers the opportunity to investigate the loss of Adnams as a prominent artist, and the extent to which she is relevant to contemporary and historical art practices. Her work was included in the Angels of Anarchy exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery in 2005, which situated her amidst women artists who had challenged the status quo. The Derby exhibition further identified Adnams as a ‘Singular Woman,’ in rewriting former descriptions of her in a positive manner. In the video ‘Discovering the Artist, I explored the idea of interacting with Adnams through her work. The concept of being in conversation with her has subsequently also been drawn upon in the Strange Coast exhibition ‘Notes from the Bunker: Talking with Marion’ by Cathie Pilkington, who outlines her project thus: ‘I have been building an installation in the cave-like space of Transition Two. It’s a coast-like assemblage. It’s a direct, personal response to the (little known) remarkable paintings and drawings of Marion Adnams (1898-1995)’ (2019).

Pilkington describes a ‘direct, personal response’ to Adnams, which seems aligned with the ‘post-feminist’ approach of considering the relevance of the artist via a form of collage. Pilkington emphasises her own discovery of Adnams as an artist, and the latter has become more well known since the Marion Adnams: A Singular Woman exhibition, and the exhibition at Dulwich on British Surrealism includes Infante égarée as one of two of her paintings on display.

So, the initial interaction with Infante égarée sought to solve the mystery of Adnams, and the crime of her exclusion. The video expresses an engagement with the artist, and begins to solve the crime and answer the puzzle, as well as opening up new questions to be resolved. One of the repercussions of investigating this artist is the idea of becoming an expert on her, which seems to imply an overarching knowledge or authority. However, in uncovering information, the detective also seems to reveal many more issues and questions to be addressed, answered or solved. As Schmidt recognises, drawing upon Gergen, in the process of being a detective, a ‘sense of individual autonomy gives way to a reality of immersed interdependence, in which it is relationship that constructs the self’ (Gergen 1991: 147). Although this proposal suggests that the self is always relational, it is this interdependence and interaction that has become significant in establishing aspects of Adnams’ persona, and also of my own. The detective work has involved engaging creatively with the artist through her work, and reinstating its significance. Has this solved the crime of exclusion? Only partly, as recuperation into the canon in and of itself can certainly challenge it, and has done so with Adnams and other women surrealist artists receiving a lot of recognition and acclaim. Infante égarée has become a popular painting for critics and reviewers to use because of its appeal. Yet every solution leads to further questions about limitation, the responsibility of categorisation, and an exploration of the role of the detective in this process.

REFERENCES

Adnams, Marion (undated), The Enchanted Country (Unpublished memoir).

Bolton, Lucy (2015), ‘Selected Bibliography’ https://sallypotter.com/uploads/websites/774/wysiwyg/Writings_About_SP_Annotated_Bibliography_2015.pdf (last accessed 2 October 2020).

Forde, Teresa Forde & Val Wood with Lucy Bamford, Co-curators (2017-18), Marion Adnams: A Singular Woman, Exhibition at Derby Museums and Gallery (2 December-4 March) https://www.derbymuseums.org/whats-on/marion-adnams-a-singular-woman (last accessed 2 October 2020).

Gergen, Kenneth J. (1991), The Saturated Self, New York: Basic Books.

Hayward, Lawrence (1943), ‘Letter to Marion Adnams about looking at her paintings’ 25/543.

Irons, Glenwood and Joan Warthling Roberts (1995), ‘From Spinster to Hipster: The “Suitability” of Miss Marple and Anna Lee’, in Glenwood Irons (ed.), Feminism in Women’s Detective Fiction, London: University of Toronto Press, pp. 64-73

MacDonald, Scott (1988), ‘Sally Potter’, Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers, Berkley: University of California Press. pp. 397-428.

Maslin, Kimberley (2016), ‘Writing a Woman Detective, Reinventing a Genre: Carolyn G. Heilbrun as Amanda Cross’, Clues: A Journal of Detection, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 105-115.

Meskimmon, Marsha (2003), Women Making Art: History, Subjectivity, Aesthetics: London, Routledge.

Mills, Kathryn Oliver (2007), ‘Duality: The Human Nature of Detective Fiction’, in Linda Martz and Anita Higgie (eds), Questions of Identity in Detective Fiction, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, pp. 175-182.

Pilkington, Cathie (2019), Strange Coast. Notes from the Bunker: Talking with Marion, 25 May-23 June http://www.transitiongallery.co.uk/htmlpages/Transitiontwo/StrangeCoast_conversation.html (last accessed 2 October 2020).

Rosemont, Penelope (2001), ‘Introduction: “All My Names Know Your Leap”; Surrealist Women and their Challenge’, in Penelope Rosemont (ed.), Surrealist Women, London: Bloomsbury.

Rose, Marilyn J. (2014), ‘Under/Cover: Strategies of Detection and Evasion in Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace’, in Marilyn J. Rose and Jeannette Sloniowski (eds), Detecting Canada: Essays on Canadian Crime Fiction, Television, and Film, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, pp.91-117.

Schmidt, Nete (2015), ‘From Periphery to Center: (Post-Feminist) Female Detectives’, Contemporary Scandinavian Crime Fiction, Scandinavian Studies, Vol. 87, No. 4 (Winter), pp. 423-456.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey