Finding a Voice

by: Katherine Gilmartin , September 12, 2018

by: Katherine Gilmartin , September 12, 2018

Art has the ability to create reaction. It can open up a space for connection and compassion. It can heal trauma by bridging the void between what is seen as acceptable and the ‘othered’: this is the vast sea of disconnect trauma can bring. A painting can boldly shout about a shared reality and gently soothe the isolated mind: you are not alone. My work continues to assist me to process, open and close boxes of emotional unknowns, and, I hope, it is also able to help others to heal.

Learning how you think is an exciting experience. Learning how to use your voice is scary and exhausting. Non-verbal communication, making and painting are often overlooked, closed and shut off as hermetic, personal, one-way conversations. Looking back at my processes developed in arts education, installations and drawings, I can see what I wasn’t willing to say. An inner monologue silently screaming and yearning for containment. Courage and honesty means narrowing the gap between what I mean and what I draw unapologetically and with purpose so I am no longer cut off or looking to the audience for my own meaning.

As I have gained ownership over my own voice and intention, there has been an increasing overlap visible in my character and abstract work; the catalyst and motives are rooted in the same place of my experience. I had my only child at twenty-one. It was a traumatic birth and its physical violence was visible only to me afterwards. I avoided the cutlery draw for months and salad tongs still make me turn away. Though having come from a background of trauma, it didn’t seem to touch me. As with the pain which came before, I skilfully disassociated and didn’t talk in detail about the process until years after, when I was working through PTSD therapy for previous events. Talking and emotional vocabulary wasn’t in my family culture.

Having a rude awakening to emotional dialogue and responsibility in my early thirties – a decade after giving birth – has shown me how little autonomy I had back then, how unconnected I was and how much pain I was avoiding. Through drawing and painting I am able to tear open discomfort via a shared experience with female bodies that have been pregnant. What I find most significant in my recent work is that the violence of reproduction echoes other bodily traumas. Birth is romanticized and maternity is given saintly status, but postpartum is unclean, unseen and shamed. The significance of teeth in my work suggests that I am not soft or toothless. I have bite. I am not a victim who is ferociously defending myself and that which I cherish. Teeth surrounding eyeballs, or vulva, gums removed to reveal roots that mimic monster teeth are central facets of my work.

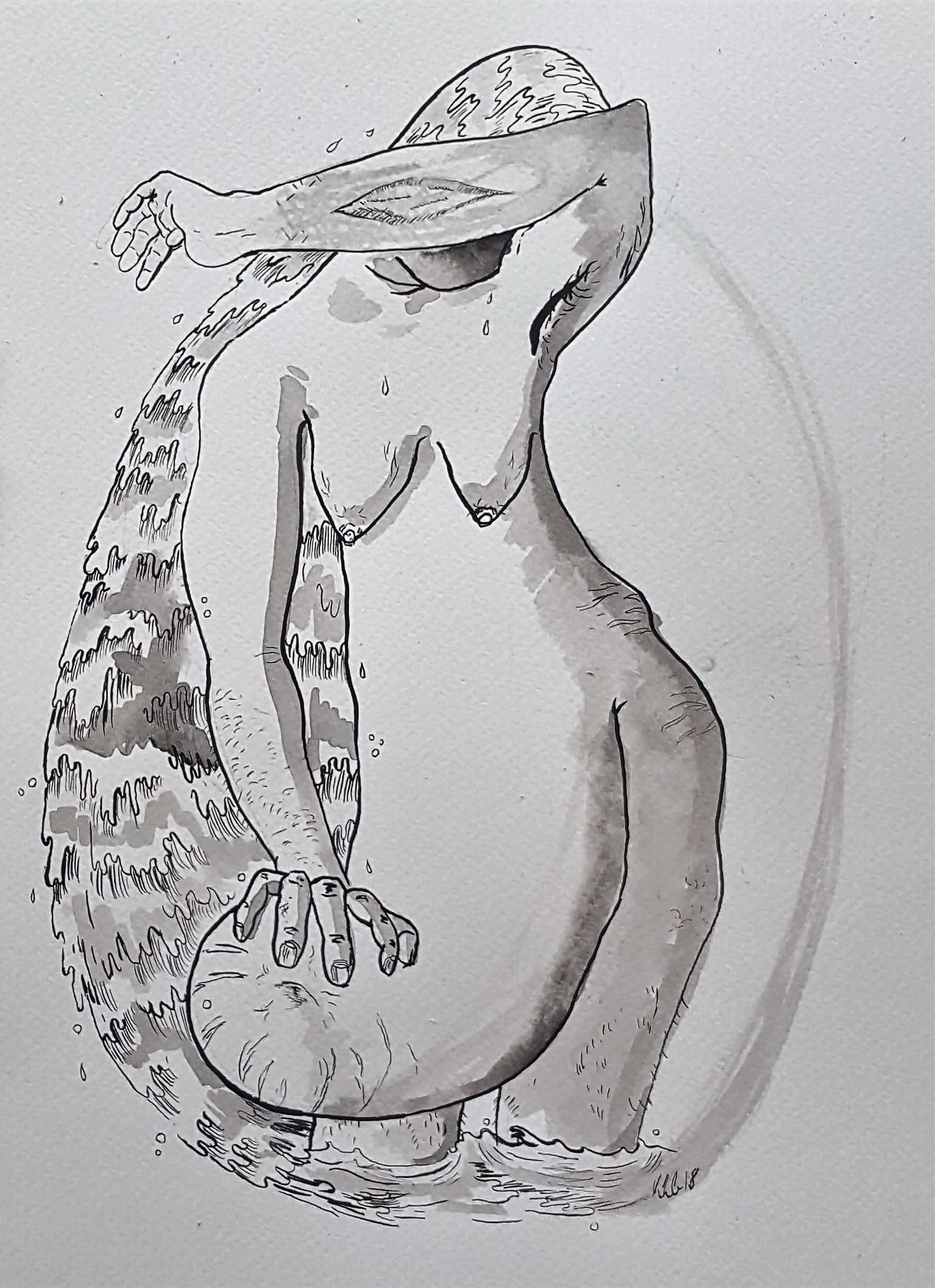

Unlidded eyeballs stare down the onlooker, unwillingly viewing, judging all. Nestled dangerously between unlipped fangs, vulnerable but powerfully seeing. Women often feel looked at, our bodies are present before we are in a room. Pregnancy, birth, and motherhood are often seen as gentle: mother and child possess a purity as an idyllic unattainable picture. The reality is internally brutal; permanently altering to body and mind, and so often traumatic. A body is viewed as it develops through puberty. It’s inhabited and not given vocabulary or space to explore or own itself before it’s put out into the world. The same can be said for a postpartum body. There is a vast culture that promotes unattainable ideals of body, lifestyle and mental health. This culture disempowers the reality of lived experience for the vast majority of us.

Using imagery to convey meaning was my first mode of honest communication. I could hint at my truths far more fluidly in an image than if I ever had to speak out loud. There is an element of peeling away the anatomy, revealing structure and layers that have been hidden or disguised: fat cells, cellulite, stretch marks, scars, hairs, stubble and lumps – undervalued flesh meeting a border of underwear. A postpartum body is deemed shameful, ruined, a state to be ‘bounced back’ from, instead of being celebrated and worshipped for the immense feat it has undertaken, the power it has undermined by avoidance. This is where my work pushes my own boundaries to the limit. Allowing space on the canvas for the top of the thigh, the cotton covered mound between elastic lace borders.

There is a subtle play of vulnerability in eyeballs and teeth, flesh and monsters, oceans and bodily fluids, internal thoughts and external tissue, innocence and sexuality. This sense of play gives space for discussion, to those who connect because they felt that too, which in turn tells me that I am not alone. For those brave enough or ecstatic in their connection can say out loud, ‘I thought it was just me!’ or ‘that is what it feels like’ and ‘this is how it looks.’ My intention is to keep pushing my edges to explore how to make space for these connections. Cutting through shame and alienation to bring those with shared experience a greater sense of validation, empowerment and self-compassion.

Enthusiastically exploring edges of what I’m capable of is both indulgent and generous. Without space for this thought, this type of therapeutic process, it is easy for rot to set in. If there is no space for openly discussing trauma, it can sit in a person and slowly destroy them. The kind of intimate trauma birth brings along with this current culture can cause serious misconceptions about what is within the realms of normality and health. Allowing space for a creative process or discussion can close and soothe wounds that would otherwise sit raw and unregulated; thoughts and memories that undermine a mother’s confidence, compromising the connection between mother, self, body, child, and society. I believe there should be more access to mental health care built and linked into current services and a greater emphasis on what to expect after various types of birth. A tick sheet on wellbeing and gentle encouragement to go to a mother and baby group, in my experience, isn’t enough. What remains with me the most is that post-birth behaviour is a closed loop of family culture. You can only do as well as your mother did, which in some cases is far from well.

What I give out visually is a fraction of a story, a narrative that is personal. Within that giving is an almost tangible element for an audience. That little bit of human nature and struggle is what I use and play with and what an audience might connect with. The recurring motifs are aggressive and strong, soft and vulnerable, bodily and monstrous. My work is about finding a voice – my voice – so that I can authentically speak for a collective of shared experience in childhood and parenting. Finding the words for past trauma enables me to work out subsequent pain and lack of a voice; accepting the need to talk and growing the confidence to let myself take up space allows me to advocate for the importance of this collective voice being seen and heard.

Finding a Voice exhibitions and workshops are an act of broadcasting that voice, to enable more discussion around parenting through PTSD and family mental health. Initially, I invited art psychotherapist Jan Goldsworthy to my studio to creatively respond to my work and to exhibit her work alongside mine in the 2017 exhibition. In October 2018 we are continuing this dialogue. We are also inviting other families that have accessed creative therapeutic services to celebrate their own processes by exhibiting some of their creative pieces in Finding a Voice 2018. This creates a space for greater community connection. We encourage families to get involved in workshops. Janette is encouraging other art therapists to engage in this space with their clients and I have planned for workshops to help educate local authority services on lived experience of various professional approaches within children’s services and mental health services.

& THAT’S OK (2016), ink on paper

Sea-ing#1 (2018), ink on paper.

Seeing & Holding Her (2018), oil on canvas.

A Response

Jan Goldsworthy

This is a collaborative journey with Katherine Gilmartin about being female and being a mother and also being an artist.

My art is a response to feelings we all experience to a lesser or further extent. These works are in relation to finding a voice of what it is like being on the inside of being female.

I have been on a journey since 2000 working in the area of mental health as an art psychotherapist. I have been asking questions to families about their attachment in response to the dialogue of image making in the hope of finding a shared meaning and understanding to their dilemmas.

When my daughter was born fourteen years ago I experienced pre-eclampsia first hand, not knowing what this condition could lead to. Birth trauma is emotionally and physically distressing and leads to further complications if not treated.

‘It is an event in the delivery process that involves the perception of a serious injury or death to the mother of her infant and is associated with strong feelings of fear’. (Beck 2004)

Many women don’t come forward to talk about their experiences of birth trauma and/or pre-existing trauma before birth or even in their childhoods themselves. The art process can aid healing and potential growth to overcome major negative life events.

We are collaborating, joining our experiences and voices together. These perspectives may have been unseen and unheard previously. We are hoping that other people can join us and respond, and also help them find a way to voice unspeakable or indescribable things themselves. Words can help, but we first need to process our feelings in order to find words for these experiences. The art image is direct and powerful and reveals many hidden truths.

REFERENCES

Beck, Cheryl (2004), ‘Birth Trauma: in the Eye of the Beholder,’ in Nursing Resources (January-February 2004), Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 28-35.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey