Feedback As an Act of Love: How to Transform Storytelling By Listening to Others

by: Alexandra Hidalgo , June 14, 2021

by: Alexandra Hidalgo , June 14, 2021

‘If I hadn’t had to read this story for class, I wouldn’t have finished it,’ she said as she pointed at the short story I’d laboured over for weeks. ‘I hated the characters. Who wants to read about upper-middle-class Venezuelan women? Stories about Latino characters should be about poverty.’

My cheeks were burning, which I knew meant that my face was flushed, betraying my embarrassment as she kept enumerating the multitudinous writerly crimes I’d committed. I kept hoping that one of my fellow MFA students sitting in the classroom where until now I’d felt safe would rescue me, but they remained silent.

By the time she complained that my use of the word ‘sofa’ instead of ‘couch’ was pretentious and alienated readers, I stopped listening. I have no recollection of how the discussion ended, but I do know that my professor, a kind yet reticent man, didn’t intervene on my behalf.

I rode home that afternoon with tears blowing toward the back of my face and tickling my ears as I sped down Boulder’s ubiquitous bike trails. While replaying the event in my mind, I realized my classmates’ and professor’s silence had been the result of the same shock at her outburst. Naropa University was founded in 1974 by Chögyam Trungpa, a Tibetan Buddhist teacher who invited poets Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, John Cage, and Diane di Prima to create a writing program using Eastern spiritual teachings as a lens through which to harness creativity. When I entered the program in 2002, that focus was very much alive. Our requirements included yoga and meditation courses, and at readings we’d close our eyes as a gong played, uniting us with storytellers whose imagination had vibrated to the same haunting sound for centuries.

During my two academic years and three summers at Naropa, I took a litany of workshops, and only once did I witness the school’s philosophy of spiritual connectivity break. That I should have been the recipient of that rupture is fortunate, regardless of the self-pitying thoughts that were flashing through my mind as I pedalled home. I have spent the two decades since that afternoon figuring out how to give feedback that does the opposite of what my classmate did when she ripped my unsuspecting story and its author to shreds. In this essay, I share those findings with you so your work can soar as high as the Rockies and be as enlivening as the crepuscular light falling on them while I rode with tears on my cheeks and ears that day.

The Clunky Big Heart of Feedback

As a writer and filmmaker who is an associate professor at Michigan State University, I spend much of my working hours giving and receiving feedback on my own and others’ writing and films. Listening to and implementing feedback is, I believe, the most effective and (usually) enjoyable way to make art that audiences connect to. Yes, there are exceptions. Emily Dickinson laboured in secret her whole life, and her posthumously published poems continue to beguile readers over a century after her passing. However, most of us, even when extraordinarily talented, are unable to produce exceptional work in isolation. Besides, artists have something to share that we hope will touch others. Feedback—the right kind of feedback—is the surest way to make that wish come true. The question I seek to answer here is what the ‘right kind’ of feedback is, and how we can nurture, interpret, implement, and reciprocate it throughout our storytelling careers.

Anne Lamott, memoirist and provider-of-writing-wisdom extraordinaire, has four students who formed a writing group. She tells us that ‘[t]hey all look a lot less slick and cool than they did when they were in my class, because helping each other has made their hearts get bigger. A big heart is both a clunky and a delicate thing; it doesn’t protect itself and it doesn’t hide. It stands out, like a baby’s fontanel, where you can see the soul pulse through’. (1995: 159) The process of giving and receiving feedback makes our hearts grow because sharing the right kind of feedback with another is an act of love. You have to pay close attention to a person’s creation, to notice and appreciate the elements that work and the ones that don’t. You then have to express your discoveries in a way that invites reinvention. You aim to create a spark without burning down the fragile structure that is someone’s in-progress project. The right kind of feedback is cautious and optimistic, a precarious act of faith and infinite possibility.

I began this essay with a story about receiving the wrong kind of feedback and turning that moment into something positive. I was in my mid-20s at the time and mature enough to see that, humiliating as it was, whatever transpired had not been about me or my writing. I’m proud of my younger self who brushed it aside and kept working. I am less impressed by two instances that also took place while at Naropa when I ignored to the right kind of feedback, taking those who delivered it for granted.

Lessons Learned from an Impatient Youth

I was (and still am) a staunch admirer of Zadie Smith’s delectable prose. That she’d published her trailblazing debut White Teeth at 25 made me feel like I was behind schedule. That coupled with the fact that Jack Kerouac (after whom our writing program was named) had written On the Road during a feverish three-week period made me impatient to get my own novel on bookstore shelves. Never mind that I found On the Road to be a frustrating read with alarmingly sexist passages, I felt like I was running out of time. Someone should have told me that art is not like basketball. Artists aren’t forced to retire when their still-young bodies can no longer fly toward a hoop. Art is a mature person’s game. It takes patience, wisdom, and life experience. Yes, there are prodigies, but if they want to remain relevant, their art must evolve and evolution always takes time.

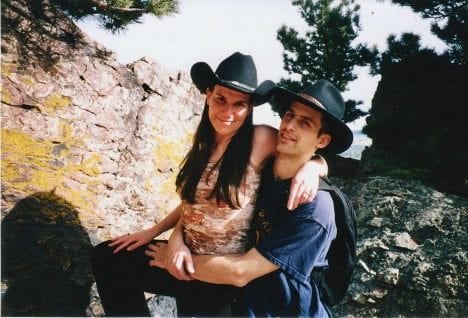

Someone should have told me that art is not like basketball, but even if they had, I would have ignored them. I was too enamoured with my immediate future as a successful author to listen to anyone who’d question its impending arrival. As I laboured on my thesis, a novel about the daughter of a Venezuelan pop singer, the pages kept piling up with intoxicating heft. I didn’t get it written in three weeks, but I might as well have for how rushed I was. My husband and fellow writer Nathaniel Bowler would read my chapters and write generative marginalia. At night, we’d discuss his feedback in bed, the pages sprawled around our intermingled bodies.

One of Nate’s most consistent critiques concerned the novel’s prose. Being constructive in his feedback, he didn’t say that my prose was flat or rushed (it was) but that my language could be more poetic. We have too strong a relationship for his critique to come between us, but I was frustrated by the recurring note, countering that poetry wasn’t something one just made happen. Poetic prose resulted from some ineffable divine inspiration. It either emerged or it didn’t. How could he keep asking me to do something that was out of my control?

I’m awed by how much nonsense I was willing to believe to protect my dream of being a prodigy. Yes, our culture is brimming with legends about revered songs, poems, and novels that seemed to write themselves. Early-career Bob Dylan is the poster child for that kind of inspiration. However, for the rest of us (and for late-career Bob Dylan, for that matter) poetic prose emerges after labouring for long hours—or days—over a passage until the words finally sing.

Not content with ignoring Nate’s feedback, I didn’t listen to my friend Andrew Wille either. Andrew was a fellow MFA student, and unlike the rest of us, he’d worked in publishing for years. He’d been an editor at Little Brown, UK and nurtured the talent of renowned authors like David Foster Wallace, RuPaul, and Rosario Ferré. We became close and exchanged stories outside of class, discussing our feedback over wine and nachos at the stylish Boulderado hotel. Andrew helped me improve not only my writing but also my editing skills, pointing out what was and wasn’t good feedback. In one of his stories a character had a penchant for varying her lipstick color depending on her mood. When I (not a big makeup user, mind you) commented that women usually stick to one shade of lipstick, he replied that when giving feedback we shouldn’t push our vision but rather let authors bring their own to life. In other words, point out inconsistencies but don’t try to control the author’s world and characters. And for god’s sake, don’t be petty.

When I finished my novel, Andrew generously offered to do a full edit on it. It took him a few weeks and I decided I couldn’t wait. I had to reach out to agents with my masterpiece. By the time Andrew returned the novel with comments on the margins and a set of generative suggestions, I’d already decided that the novel was ready. As you can imagine, I never made those changes and I never got an agent or that multi-city book tour I was sure was just around the corner.

I don’t think the novel, which was the result of a young girl’s delusions about what the creative life entails, would have gone anywhere. I regret neither writing nor abandoning it. It was one of many failed experiments on the path to figuring out who I am as an artist. What I do regret is how I overlooked the gifts of love that Nate and Andrew offered with their feedback. Luckily, they were both kind enough not to hold it against me. Although he lives in London, where he works as an editor and writing teacher, and I in East Lansing, Andrew and I still provide feedback to each other from time to time. Like we did two decades ago, we continue to talk about the books and films that delight and puzzle us. We philosophise about the artist life and how we’ve continued to evolve.

The most drastic evolution for me has been that I’ve left fiction behind to focus on documentary filmmaking, memoir, and film and TV criticism. Everything I learned about fiction at Naropa still applies. A good story is a good story, and although each medium has its peculiarities, they all need to move and engage the audience. This essay is my plea for storytellers to find and treasure the right kind of feedback. Hear me out and your creativity will blossom.

Why Feedback Hurts and Why We Still Need It

Anyone who peruses Rotten Tomatoes knows that critics don’t just say they don’t like a film, they craft some witty, pun-involving takedown that deliciously encapsulates some fatal flaw in the work. And critics are the ones so committed to loving the moving image that they make a living by writing about cinematic and TV creations. Scroll down to readers’ responses to any review or to Twitter and Reddit feeds about something as seemingly innocuous as the Star Wars reboot and you’re entering a vitriolic world where artists and their families receive all manner of unspeakable threats.

As usual, what transpires in the culture at large is a reflection of our personal lives. Brené Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston who studies courage and vulnerability, explains that ‘many of us were raised in families where feedback came in only one of two packages—shame or blame. Giving productive and respectful feedback is a skillset that most of us have never learned’. (2018: 200) As if it wasn’t difficult enough to be an artist, we make and distribute our creations in societies where many don’t know how to engage with our work (and each other) in a constructive manner. We can and should try to change that society, but even as we do so, we need to learn to process feedback—the right and the wrong kind.

Scottish filmmaker Diane Bell epitomises the central lesson for analysing feedback when she writes, ‘Set your ego aside. This is not about you. It’s about your work’. (2018: 29) When people say they don’t like your film or your novel, it doesn’t mean they don’t like you personally. Survival and sanity as an artist depend on making this distinction: You are not your art, even though your art comes from you. That becomes even trickier to do when you’re a memoirist. My in-postproduction feature documentary A Family of Stories follows my investigation into my father’s life and his 1983 disappearance in the Venezuelan Amazon, and how secrets I discovered about him and myself in the process transformed my life. I narrate the film and interact with my father’s friends and family as I untangle the enigmas he left behind.

During feedback sessions on countless drafts of A Family of Stories, we invariably turned to my character. For years, viewers found her detached and, as a result, less compelling than everyone else—a major red flag for a protagonist. Because I learned my lesson on wasting valuable feedback at Naropa, I’ve been able to see the on-screen Alexandra Hidalgo as separate from me. I was frustrated by the persistent conundrum of how to make my character compelling. However, I tackled it like I tackled other stubborn shortcomings—without feeling that viewers were pointing out my inadequacies as a human being. After countless failed iterations of my character, viewers finally reported connecting to me at our feedback sessions last year. Well, not to me, but to the version of me we brought to life onscreen. If I’d taken viewers’ misgivings as a personal attack, we would have never fixed the issue. Moreover, I’d have spent countless sleepless nights over audiences not relating to what is merely a representation of me. Even if you’re a memoirist, remember that what audiences react to is a crafted version of you, not the actual you.

When requesting feedback, I tell people I want to hear what they honestly think because as long as I’m working on a project, I can try to address the frailties they identify. The saddest part of our culture’s ritual of humiliating artists is that the work is finished by the time audiences pass their strident judgments. At that point the artist can use whatever insight they manage to glean from the debris for future projects, but they cannot revise the work currently getting scorched. I can’t guarantee that your work won’t be attacked, but if you engage with the right kind of feedback over multiple drafts, you’ll be more likely to produce work that connects with a substantial portion of your audience. That connection, above anything else, can drown out negative reactions.

Another way to process negative feedback is to remember that, as Diane Bell argues, ‘The aim is not to make a single film, but to make many … Like any art or craft, filmmaking needs to be practiced in order to be mastered’. (2018: 8-9) Think of your career as an incomplete story you’re telling yourself and the world. Take what you learn from the triumphs and weaknesses of your latest project and apply it to the next and the one after. The story of your career should be as long as your life and the arch of it one of constant improvement, even if you end up producing some misfires along the way, and trust me—if you have a long career, you’ll have misfires, and you will, as much as it may hurt, eventually learn from them.

The Ones Who Silence Your Voice and Blind Your Vision

Before I tell you about finding people who give you the right kind of feedback, I want to warn you against those who come bearing the wrong kind. Being fond of happy endings, I decided to get this over with early on so its taste doesn’t linger. Having my story ferociously attacked might have been a rare event at Naropa, but it is a rite of passage for artists. At some point in a workshop or feedback session someone is bound to go off on an irrational rant about your creation. The fact that the rant is irrational makes it no less distressing while it’s being delivered, though it’s a useful thing to ponder as we lick our wounds afterwards.

Bell describes the givers of the wrong kind of feedback as those who ‘sabotage’ the work. ‘They’ll tell you every single thing that’s wrong with it, and you’ll leave them feeling depressed, like you’ll never write again’. (2018: 30) Such feedback doesn’t only crush your belief in your current project, but also your ability to undertake the creative enterprise altogether. And if you’re a creative person (and I’m guessing you are if you’re reading this), much of your happiness is linked to connecting with others through your art. When someone crushes that side of you, they’re crushing a vital part of your identity. They are, in other words, dangerous to the piece you showed them and to your wellbeing as a whole.

Some of these people will announce themselves with their anger, but others will seem gentle as they deliver their blows. Lamott warns us against a critic who ‘says things about your work, even in the nicest possible tone of voice, that are totally negative and destructive … He says how sorry he is that this is how he feels. Well, let me tell you this—I don’t think he is.’ (1995: 169) I agree with Lamott that those who give the wrong kind of feedback are rarely sorry to inflict wounds on the one receiving it. Allow me to indulge in a bit of armchair psychology by saying that mean-spirited feedback tends to come from those who are frustrated with their own creative endeavours—or with the fact that they gave up on their artistic aspirations long ago—and they take that frustration out on you.

Any sane artist will tell you never to seek feedback from that person again. As you heal from the encounter, it is good to take Brown’s advice, ‘Don’t grab hurtful comments and pull them close to you by rereading them and ruminating on them. Don’t play with them by rehearsing your badass comeback. And whatever you do, don’t pull hatefulness close to your heart’. (2018: 21) Give yourself a few days to process the event, remembering that this is not about you but about them. This person is suffering, and they’ll hopefully heal at some point. You have to move on, though. Find a couple people who know how to give the right kind of feedback, show them your work, and use their ideas to rebuild your piece and your confidence.

The Ones Who Amplify Your Voice and Clarify Your Vision

Bell uses ‘feedback friends’ to refer to those who give the right kind of feedback. She says, ‘a good feedback friend seeks to understand what the writer is aiming for and helps them achieve it … They’re really trying to see the film as you see it, but are objective enough that they can help you see what isn’t working. Being a good feedback friend is a skill that you should develop yourself, so you can be one to others’. (2018: 27) Like a good friend, a feedback friend wants to support your endeavours without imposing their take on how things should unfold. They are close enough to foresee emergent possibilities suited to your particular vision, but distant enough to notice inconsistencies and wrong turns that you, like every other artist, are bound to miss in your own work. Like a good friend, they know how to deliver praise in a way that doesn’t make you think everything is perfect and criticism in a way that gets you excited about addressing the issues. It may take a few days to process their suggestions, but eventually they should become a springboard for your work.

Lamott describes her long-term feedback friends as ‘life midwives; there are these stories and ideas and vision and memories and plots inside me, and only I can give birth to them. Theoretically I could do it alone, but it sure makes it easier to have people helping’. (1995: 164) When you find a feedback friend who helps you birth the stories you want to tell, hold them close, and as Bell suggests, reciprocate. Most of my long-term feedback friends are fellow filmmakers and writers, and I return the favour by commenting on their work. Others are not. My friend Caitlan Spronk, a software engineer, has little to gain from my storytelling advice, but we often go thrifting, buy swanky outfits, and take portraits of each other and our families. The resulting photos adorn our homes and our social media accounts, a reminder of our creative bond. There’s always a way to bond with your feedback friends. Find it and revel in it.

Harnessing the Wonders of Collaborators

In her Pulitzer-winning meditation on writing, Annie Dillard notes, ‘It should surprise no one that the life of the writer—such as it is—is colourless to the point of sensory depravation. Many writers do little else but sit in small rooms recalling the real world’. (1989: 44) I have written the first draft of the section you just read while Nate and our sons build a Lego set a couple feet away from me. After nine years as a working mother with an aversion to desks, I’ve learned to drown out the world around me while sitting cross-legged on the couch wrestling with ideas and metaphors. Dillard is right that to craft stories we need to tame our minds into focus. Whether we’re alone in small rooms or typing away as our husband and children play, we must indeed isolate our minds in order to write.

Filmmaking is a more social genre, of course, but even when I film my children for my documentary explorations of motherhood, I am separated from them. I am no longer with them but watching them from behind the lens, an observer hoping to capture the essence of what she sees. Moreover, as any filmmaker knows, the brunt of the creative experience does not occur behind the camera but when we edit the footage. As we rewatch hours of recorded moments to find the heart of our story, we are once again removed from the world, lost in representations of it as we try to evoke some truth (minor or transcendent) for viewers.

Creative solitude turns us myopic when it comes to our work. We lose track of its boundaries as they bleed into our reality. Our collaborators remind us where those boundaries stand as they shape the story alongside us. Collaborators have skin in the game of your work. Part of themselves is attached to the piece in a way that affects their own careers. They are vulnerable to the project’s deficiencies and stand to benefit from its achievements.

Editors—the ones whose name is attached to the publication—are a writer’s main collaborator. Editors work through various drafts, providing feedback and helping you figure out how to implement it. They sigh in relief when an issue gets resolved and mourn the crevices that emerged when you fixed that issue. Draft after draft they, brilliant feedback friends that they are, help you get closer to something that connects with readers until you are both ready to let go.

Filmmakers collaborate with countless crew members and with those who appear on the screen. The most sustained collaborations happen between directors, producers, and editors. Your producer keeps your dreams realistic. How much money can you raise and how can you make the best possible film given that sum? It’s an ongoing and vital give and take. It is with your editor, however, that you’ll spend endless hours shaping the story. Bell writes that when deciding to hire an editor, you should ask yourself, ‘Do they just follow your instructions, or do they add value, contributing genius ideas of their own? That’s what you want—someone with the right sensibility who also brings fresh eyes and perspective to the material you’ve shot’. (2018: 93)

Cristina Carrasco is my editor for A Family of Stories, and we have spent three years collaborating on the film. We work furiously for months and then take long breaks to replenish our ideas (and our funding). We have prolonged philosophical conversations about the cinematic language and the themes our documentary explores. We spend hours editing a 30-second clip, only to cut it on the next iteration. It’s the kind of patient dedication that only a collaborator can give you, and it has taught me more about filmmaking than anything else I’ve ever done. When the relationship works, a collaborator is a feedback friend who revolutionises your project and your overall approach to storytelling.

Your Feedback Partner from Meet Cute to Happily Ever After

In the spring of 2000, I studied abroad in Moscow. We spent our weekdays conjugating verbs like elementary school children in our hesitant, emerging Russian. During the weekends, we once again became cerebral college students, roaming the city’s museums and theatres to experience the world that shaped our literary heroes. It was at Yasnaya Polyana, Leo Tolstoy’s winter home, that I ran into Sofia Tolstoy’s desk. Less grandiose than her husband’s, it played a vital role in his formidable career. It was there that she’d spend her evenings editing his writing and copying it in her elegant handwriting. She did this for seven drafts of War and Peace, a novel lengthy enough that it can be used as a murder weapon.

I’d always wondered how Tolstoy captured his female characters’ essence in a way that resonated so acutely with women from completely different cultures and generations. As I stared at Sofia’s desk, I realised that her influence must account for some of the connection I feel with Anna Karenina and Natalia Rostova. It wasn’t just the love, famously complicated as it was, that Sofia and Leo felt for each other, but the fact that she had been his (unofficial) editor for most of his career. She had a long view of his storytelling trajectory that was likely almost as rich as his own. She was more than a feedback friend or collaborator. She was his feedback partner.

We’re fascinated by couples who manage the intricate balancing act of creating work together. Amy Sherman-Palladino and Daniel Palladino have spent over two decades co-producing, co-writing, and co-directing some of TVs most beloved shows, like Gilmore Girls and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. At pitching sessions, they act out scenes together, playing various characters to bring a show to life. Joan Didion and husband John Gregory Dunne wrote their journalism and novels separately, but collaborated on the screenplays for classics like A Star Is Born and The Panic in Needle Park. Agnès Varda and Jacques Demy usually worked on their films separately, but when he was dying of AIDS, she adapted his memories of growing up during World War II into a stunning film. At the Jacquot de Nantes set, Demy watched his wife direct actors as they brought his childhood to life. It’s hard to imagine a more tender ending for a man who spent his career making beguiling musicals about love and heartbreak.

Nate and I have spent 22 years editing draft after draft of each other’s writing, and he reluctantly works as the cinematographer for my films. We untangle each other’s creative visions and tackle our artistic anxieties together. In a lifetime of magnificent feedback friendships and collaborations, no one is more pivotal to my success and sanity than my feedback partner.

I have talked about couples because they tend to be particularly captivating to the culture at large and to me personally. However, your feedback partner can be linked to you in countless ways. Siblings, friends, cousins, neighbours—it doesn’t matter as long as the affection runs deep, the feedback resonates, and the relationship nourishes both of you through the ups and downs that will invariably come. Just keep walking into that creative sunset together.

Setting Up Generative Feedback Sessions

When you’ve exhausted your ability to fiddle with a draft, it’s time to get some feedback. You can do it individually or in small groups. For groups, aim for four to six people so you gather a variety of opinions but everyone gets to speak. You should run two or three separate sessions to get a full sense of the draft’s strengths and weaknesses.

It is vital to get feedback from fellow artists who work in the same medium. They understand the creative process and know how to evaluate works in progress. That expertise can also be a limitation, however. Dillard remembers publishing an essay that ‘no one had understood but a Yale critic, and he had understood it exactly. I myself was trained as a critic. I was a critic writing for critics: was this what I had in mind?’ (1989: 54). She ended up rethinking her approach because writing for other critics was not in fact what she had in mind. I’m guessing that you also aim to create work that can be appreciated beyond the confines of Yale. In order to do that, you need to get feedback from non-artists as well.

Bells suggests that you bring in ‘the ideal audience member for your film’ when inviting non-filmmakers to give you feedback. (2018: 27) Every film and piece of writing has a target audience. For A Family of Stories, our target audience is (not surprisingly given the title) interested in family sagas. If I invite someone who only watches horror films and they don’t like the draft, it will be hard to distinguish between legitimate storytelling issues and the reactions of someone who is simply not compelled by my genre. It is also wise to invite people who are smart and nuanced in their thinking so they can turn their luminous minds towards improving your work.

Once you have everyone together or you’re sitting one-on-one with your feedback friend, cover the following topics in roughly this order:

- My editor Cristina always starts by asking, ‘Did the story hook you? Why? Why not?’ It’s a great opener because everything rides on this. People either want to stay with your story or they don’t. You can also ask them to assign numerical value or grades to the film.

- I then ask people to tell me what they think the story is about. If they can’t find the theme or if they tell me that there are various themes competing for their attention, I know the draft’s structure is unclear.

- Ask about your protagonist and major supporting characters. Do they relate to these characters? Is their journey clear? If audiences can’t connect to the characters, they won’t care about the story.

- Ask what confused the audience, what went on for too long, and what felt rushed. These are usually easier issues to fix than the ones above, but they make all the difference between a draft that works and one that doesn’t.

- Beginnings and endings are key, so find out whether yours are working and why they fail or succeed.

- If you suspect something isn’t working, ask about it, but not till the end. People are susceptible, and you don’t want to skew their reactions by mentioning your doubts about an issue before you’ve covered more general questions.

- I always end by asking if there’s anything else they’d like to share. Some of the most valuable feedback usually happens here because we’ve examined the whole story together and innovative ideas start flowing.

For individual sessions, Bell suggests to ‘take them out for a coffee and have a chat with them about it’. (2018: 27) Food and conversation are vital. I host group feedback sessions at home and serve a spread of appetisers and desserts, as well as wine, beer, and juice. I want people to know how much I value their time and to feel comfortable, so I create a party-like atmosphere. That gesture is crucial because besides asking them questions, I say nothing but simply type up their answers with a researcher’s impassive face.

I can’t stress enough the vitality of staying quiet and letting the conversation unravel without you. If you intervene, you’ll miss out on crucial interactions, especially from those who are introverted or need more time to process what they want to say. Don’t worry about awkward silences. They often precede breakthroughs as people try to figure out how to mention a thorny shortcoming. When it’s over, thank everyone profusely then send them an email the next day explaining how much you appreciated their feedback and generosity in engaging with your work.

How to Process Feedback in Generative Manner

After everyone leaves a feedback session for A Family of Stories, I have a glass of wine and discuss my general impressions with Nate, my feedback partner. At that point everything is foggy and I’m working through relief over what has been fixed and disappointment over what continues to be broken. I let those feelings percolate for a few days and then read my notes from the screening, where I’ve written not only what was said but who said it. I spend a day preparing the document for Cristina by colour-coding the text. Green for statements about what works, purple for what doesn’t, and blue for what is confusing. To give her context, I provide information about each feedback friend. Their age, gender, nationality, profession, and whether or not they’re involved in the film industry. Finally I summarise the main trends gathered from the session as signposts for us. When Cristina has processed the feedback, we have a long conversation over what we’ve learned.

As we talk, we respect our feedback friends’ wisdom. If one person has an issue, it may be a personal reaction. However, as Bell suggests, ‘[I]f more than one person says the same thing … you’ve got a problem, and it’s worth dealing with it’. (2018: 29) The question, of course, is how to deal with it. One drawback about feedback sessions is that while they’re great diagnostics, they’re less effective at pointing out solutions. For that, you need a thorough understanding of the material and creative process, so solutions often come from your collaborators and feedback partner.

One of the key issues we had with A Family of Stories was that it juggled too many themes and viewers couldn’t attach to any of them. A filmmaker friend pointed out that I opened the film by talking about lies and had lies sprinkled throughout, but it never fully materialised. It wasn’t until consulting-editor virtuosa Andrea Chignoli joined the project that we figured out how to weave the theme of lies affecting multiple generations of a family throughout the film. What takes our feedback friends seconds to point out can take months to fix, but without that gift of love we lack direction as we revise our stories.

Your Feedback Community, Your Wings

As you evolve through your artistic career, surround yourself with feedback friends, collaborators, and feedback partners you trust and whose company thrills you. Like relationships in the rest of your life, some of them are here till death do you part, while others only stay for a while. Value what they bring, no matter how long they’re by your side and reciprocate in kind. Your ability to make art that connects with audiences depends on it, and as such so does your wellbeing as an artist eager to have others see the world through your unique, scintillating perspective.

REFERENCES

Bell, Diane (2018), Shoot from the Heart: Successful Filmmaking from a Sundance Rebel, Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions.

Brown, Brené (2018), Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts, New York: Random House.

Dillard, Annie (1989), The Writing Life, New York: Harper Perennial.

Lamott, Anne (1995), Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, New York: Anchor Books.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey