Drawn from the Margins: Minicomics by Girls, Grrrls, and Wimmen on the 1990s’ Xerox Frontier

by: Rachel R. Miller , March 30, 2023

by: Rachel R. Miller , March 30, 2023

Introduction

When Sarah Dyer published the first issue of her all-girl comics anthology Action Girl Comics at the height of the girl zine explosion in 1994, she translated the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) strategies of third wave feminist zines to the pages of her comic book as a call-to-action for her largely female readership to make comics themselves. In her review zine, Action Girl Newsletter, which she continued to publish during the first few years of editing her comics anthology, Dyer highlighted her first-hand knowledge of how the comics industry, even in its alternative corners, marginalised women. For girls and young women making comics, the comics industry was alienating and largely indifferent to their work. ‘I started my comic … because I thought there were a lot of really great mini-comics and stuff being done by girls who were sending them to me, who were not getting published anywhere,’ she writes in Action Girl Newsletter #12. ‘The few outlets for female comic artists are really insular and don’t add new contributors often (or come out often, for that matter).’ [1]

Action Girl Comics was a defiant rebuttal to the comics industry’s widespread indifference to the work of a new generation of girls and young women. The comics anthology built on the resistance to misogyny and sexism that Dyer had already showcased in her self-published zines in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Reviewers and fellow zinemakers had sometimes erroneously attributed her fanzines No Idea and Mad Planet to her partner, Evan Dorkin, who contributed comic strips to fill out the space between Dyer’s interviews with bands and reviews of cassette tape singles. [2] Action Girl Comics, on the other hand, visually announced itself as unmistakably hers, with its eponymous blonde-haired, blue-eyed superheroine declaring on the first issue’s cover, ‘Yeah, like I wanted to join their club,’ as she gestured back at a clubhouse with a sign reading ‘Sooperhero Club No Gurlz Allowed.’[3] Whereas Dyer’s zines were ‘assembled in the margins’ [4] and remained there, circulated in small, close-knit networks, the self-published minicomics that girls and young women were sending Dyer demanded to be drawn from the margins and into the centre of a medium that was, in the 1990s, being reconceptualised as a powerful hybrid of art and literature.

With her work on Action Girl Comics, Dyer compellingly combined the anthology model of comics publication with the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos of third wave zinemaking, offering comics to her readers as a generative medium through which they could visually articulate their own lived experiences and fantasies as they connected with one another as readers, fans, and fellow creators. By combining her material lineage of zinemaking with her deep understanding of the comics industry and its history, Dyer utilised Action Girl Comics to instigate and sustain a wave of girls self-publishing their own comics, which, to her understanding, was the solution to the industry’s widespread indifference towards comics by women and girls. Dyer not only documented these efforts across the pages of her anthology, as well as her review zine, Action Girl Newsletter. She also meticulously preserved this body of work, keeping up regular correspondence with the readers and contributors to Action Girl Comics and collecting the self-published minicomics and zines they sent her. She eventually donated her collection of minicomics and zines self-published by ‘girls, grrrls, and women’ to the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University, situating the girl wave of minicomics inspired by Action Girl Comics alongside the work of third wave zinemakers already housed by the archive. [5] When paired with her archive, the issues of the Action Girl Comics anthology provide a record of a generation of cartoonists who have been largely forgotten in histories of subcultural media, and wholly overlooked by feminist media, comics, and zine scholars alike.

In what follows, I trace the record Dyer left to one of the largest bodies of women’s work in comics through her work on Action Girl Comics. Drawing on archival research I conducted with Dyer’s collection at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture, I argue that Dyer’s comics anthology manifested a network of ‘girls, grrrls, and women’ self-publishing their work in comics while Dyer simultaneously worked to preserve this body of comics, drawing upon her material lineage as both a zinemaker and a cartoonist to strategically utilise her comics anthology as an archival tool. While the anthology itself is often less radical than the women’s comics anthologies that came before because of its mission to publish all ages content, I investigate how the archival functions of Action Girl Comics nevertheless gave readers access to a radical body of comics that address a range of feminist concerns from racism and homophobia to sexual violence, gender identity, drug use, mental health, and much more.

In particular, I explicate how the record left by Action Girl Comics reveals a cohort of self-publishing comics makers that is much more inclusive in terms of race and sexuality than its counterpart third wave networks of girl zinemakers. In her account of the third wave’s origins in Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism, Alison Piepmeier suggests that Action Girl Comics and Riot Grrrl were the two foundations from which third wave feminism issued. [6] One of the major critiques of Riot Grrrl, however, is the grassroots movement’s overwhelming whiteness and inability to sufficiently parse the intersecting issues of race, gender, and class. [7] With its white figurehead and predominantly white contributors, Action Girl Comics replicates some of these very same issues. However, Dyer’s relentless efforts to recruit girls and young women into making and self-publishing their own minicomics, which are preserved in her collection at the Bingham Center, gave way to a much more diverse generation of cartoonists, including cartoonists of colour like Patti Kim, Ayu Tomikawa, Yvonne Mojica, Elizabeth Watasin, and Debbie Vasquez, and/or queer young women like Ariel Schrag, Leanne Franson, Watasin, and Vasquez, who used comics to visualise their lived experiences. In the third section of this article, then, I examine the minicomics of Debbie Vasquez, investigating how her minicomic Cookie stands as an example of a queer of colour critique of third wave zinemaking. Reading Vasquez’s work against Tammy Rae Carland’s canonical Riot Grrrl zine, I (heart) Amy Carter, I consider the capacity for comics to provide a critique of third wave girl zines’ underlying issues addressing the intersections of race, gender, and class.

Origins of Action Girl Comics

An all-ages comic that ran for 19 issues from 1994-2000, each issue of Action Girl Comics features contributions from a transnational cohort of artists, as well as Dyer’s ‘Action Girl Manifesto’ and her recommendations of ‘girl friendly’ [8] comics, films, music, TV shows, and even video games that her readers should seek out. Because the scope of her anthology was not just limited to the contributors of any one issue of Action Girl Comics, Dyer’s anthology actively connected her readers to a network of other girls and young women self-publishing their own minicomics, while also encouraging Action Girl readers to take action and make their own minicomics. Janice Radway asserts that ‘zines ought to be thought of not simply as texts to be read but also as acts to be engaged,’ [9] and Dyer’s editorial persona in the pages of Action Girl Comics certainly manifests this DIY ethos. As she writes in the ‘Action Girl Manifesto’ included in every issue: ‘Be an ACTION GIRL (or boy)! It’s great to read/listen to/watch other people’s creative output, but it’s even cooler to do it yourself. Don’t think you can do comics? Try anyway, even if they’re just for yourself! Or maybe think about writing for a zine, or working at shows or benefits. Volunteer! Learn to sew!’ [10]

Action Girl Comics, then, insists on a unique intervention in the ritual consumption of comic books, which, unlike the girl zines of the 1990s, were coveted collector’s items, the acquisition of which only encouraged further consumption as opposed to readerly participation in making comics themselves. [11] Wedding her two material lineages—that of DIY, self-published zines with the legacy of women-owned and operated comic book anthologies—Dyer inflected her editorship of Action Girl Comics with a charge for her readers to not just consume or collect her comic, but do it themselves and make their own comics.

Since the underground comix movement of the late 1960s and 70s, collectives of women and queer cartoonists have taken to the anthology format to build community and make their work visible, publishing key voices marginalised in the underground and alternative comix scenes in comic book anthologies like Wimmen’s Comix (1972-1992), Twisted Sisters (1976-1994), Gay Comix (1980-1998), and Tits & Clits (1972-1987). [12] But unlike these anthologies, which, drawing upon their roots in the subversive comics underground, broached topics like sex, drug use, gender and sexuality, and much more with irreverent, explicit image-text narratives, the material Dyer curated for publication in the pages of Action Girl Comics was less visually graphic and more light-hearted in tone. Included in the first issue, for instance, is the slice-of-life strip ‘Soundtrack’ by Jessica Abel, a wordless comic that depicts a girl going through her day making comics, dancing in her room, writing songs, and ending her day serving up drinks behind a bar. This story appears alongside paper dolls Dyer created of Action Girl (‘Action Girl Goes Thrifting!’ ‘New Wave Action Girl,’ and ‘Action Girl Stays Home to Work on A Zine’); the playfully surrealist stories ‘Damn Crow!’ by Rebecca Dart and ‘Reservoir’ by Megan Kelso; and cutesy farces starring the avatars of queer cartoonists Elizabeth Watasin and Leanne Franson: the covertly asexual A-Girl and proud bisexual Liliane, respectively.

On its surface, the choice to curate stories for her anthology that did not contain mature, ‘adult’ content was an aesthetic one informed by Dyer’s longstanding affiliation with the ‘girl zine’ and Riot Grrrl subcultural movements. The intensification of feminist discourse and action in the mid-1990s, often referred to as feminism’s third wave, was characterised by an ecosystem of subcultural media made by young women, including music, film, art performances, and zines, that ‘deployed the sign of the girl’ as a ‘shared aesthetic.’ [13] Although Riot Grrrl is the most well-known movement of this period, there was a widespread adoption of the girl as a figure who ‘allow[ed] the politicised adult a more empathetic, indeed erotic relationship to her former vulnerabilities and pleasures.’ [14] This is certainly true of Dyer’s Action Girl projects, including both her zine review Action Girl Newsletter and comics anthology Action Girl Comics. Littered with Hello Kitties, paper dolls, and a figurehead who was cute, spunky, and outspoken but never crass, Dyer’s zines and comics anthology took seriously the capacity for girls’ cultural production, interests, and emotional vulnerabilities to be legitimate organizing forces of popular culture. Dyer’s aesthetic deployment of the girl, however, ran counter to Riot Grrrl itself, which drew upon the same stratum of girl-centric cultural references as Action Girl, but used girlhood as a way to deconstruct and detach from the mainstream cultural values girls who are visible in the public sphere have historically embodied. Dyer’s zines and comics anthology did not trade in the same brand of irreverent making and unmaking of the girl as Riot Grrrl and its affiliates, eschewing, at least on the surface, the erotics of that project to reclaim the girl and girlhood. Instead, in the pages of her comics and zines Dyer embraced girlhood as a time of playfulness, discovery, and the considerate curation of influences and inspirations.

But beyond being merely an aesthetic choice, presenting ‘all ages’ content exclusively in her all-girl comics anthology was also a practical strategy for ensuring that Action Girl Comics would actually reach readers. Although her one-woman operation self-publishing zines had led her to her new role as an editor of a comic book anthology published by indie comics publisher Slave Labor Graphics, Dyer knew that this new ‘anthology of outstanding self-published girl cartoonists’ [15] would face a different set of challenges in finding readers than her self-publishing zines. Paramount among these was the social nature of the spaces—comic book shops and comics conventions—through which comics were circulated and distributed during Dyer’s era. Unlike her zines, which were self-published and distributed through non-institutional channels stitched together by ad hoc communities of zinemakers, Action Girl Comics was subjected to a wholly different set of spoken and unspoken strictures that structure the extensions of the behemoth comics industry in the U.S. Besides the rampant sexism of these spaces in the 1990s (as Dyer in her Action Girl Newsletter writes, ‘[i]t’s the shops that scare you, the comic stores full of Penthouse posters and guys that leer at you’ [16]), comic book shops also willfully marginalised the comics work of women like Julie Doucet, Roberta Gregory, Mary Fleener, and many more who openly addressed sex, violence, and other ‘taboo’ topics in their comics. These comics were often bagged so their covers were not visible and shelved in pornography or ‘adult’ sections. And some shops flat out refused to carry them at all. [17] Making Action Girl Comics strictly all ages did not protect Dyer’s project from the misogynist scrutiny inherent to such spaces, but it did at least give her comic book a chance to be visible in shops and, so, available to readers. [18]

‘Action Is Everything!’: Materialising an Archive and Preserving a Network through Action Girl Comics

Comics is a visual medium, but the telling and retelling of women’s history in comics is marked by their erasure from and invisibility within the industry, as well as the measures researchers have had to take to recover their work. Hillary Chute, whose ground-breaking monograph Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics was one of the first truly precise scholarly autopsies of women work in comics, cites ‘a large field of women creating significant graphic narrative work,’ but suggests that their comics always carry with them ‘the risk of representation’ (emphasis in original), the recognition of which is often used to suppress their work as too graphic or explicit. [19] By visualising that which has previously been unspeakable or invisible, the women engaged in the graphic life writing that she analyses have all ‘directly faced censorship at some point in [their] career[s].’ [20] But outright censorship is just one of many ways in which women’s work is marginalised and made invisible in the comics industry. Gatekeeping both within the mainstream and alternative factions of the industry, as well as the conventions that structure the spaces in which comic books and minicomics circulate, some of which I outlined in the previous section, often prove to be subtler, more insidious ways of erasing women’s efforts and history in the medium. Indeed, unlike some other industries, the comics industry is an intensely interconnected ecosystem, which means that the mainstream—a historically inhospitable place for women and other marginalised creators—always, to some extent, dictates the legibility of graphic narratives published in other sectors of the industry, such as the alternative or ‘indie’ comics scene in which Dyer published Action Girl Comics.

Dyer was particularly percipient to both the interconnectedness of the alternative and mainstream comics industry, as well as the machinations through which the industry worked to make women’s efforts invisible, both in her contemporary moment and historically. Thus, Action Girl Comics is, like the anthologies published by collectives of women who came before her, centred around making the work of women and girls more visible. Dyer engages some of the strategies of mainstream comic book culture to do this work. Action Girl herself, for example, is a superhero—the talisman of mainstream comic book culture—who, through the paper dolls Dyer offers readers in the pages of the anthology, can transform into a punk, a zinemaker, a ska fan, or don any number of retro, time-hopping costumes designed by Dyer.

Most importantly, Dyer wed her understanding of both mainstream comics’ conventions and women’s history in comics to her third wave informed approach to networking with readers. This DIY ethos, developed through her years of zinemaking, effectively transformed the all-girl comics anthology into an archival system that would far outlast the comic book’s lifespan on the shelves and back issue bins of comic shops across the country. As Brigitte Geiger and Margit Hauser point out, since the second wave, feminist print media has played a variety of roles from within and without different movements. They write, ‘feminist media serve as both a means to information, communication, and discussion within the movement, as well as a means to self-determined expression to the “outside.”’ [21] But, as Red Chidgey asserts, feminist media also ‘enact an archival function: they move feminist memory out of the realm of the institutional and create grassroots memory texts that are mobile, shared and networked.’ [22] This was exactly the work that Dyer did in the pages of Action Girl Comics. Calling her readers to create and self-publish their own comics, she simultaneously kept a record of their output within Action Girl Comics through the conventional features of the comic book itself—letters pages, author bios, letters from the editor, and Dyer’s own back pages in which she recommended minicomics for her readers to seek out.

Donating her collection of zines and minicomics to the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University in 2000, with additions made in 2002, 2006, and 2008, Dyer had already been using her anthology to keep a record of the girl wave of minicomics that Action Girl Comics instigated and bolstered throughout the mid-to-late 1990s. Decades later, I used this record in tandem with the Sarah Dyer Zine Collection itself to uncover one of the largest bodies of women’s work in comics that I have encountered in my years working with comics created by women and girls. Like previous anthologies of women’s work such as Wimmen’s Comix, Twisted Sisters, or Tits and Clits, Action Girl Comics served as a platform to make the comics work of women and girls more visible. Crucially, however, Action Girl Comics diverges from previous iterations of comics anthologies by and for women because, by deploying the strategies developed by third wave girl zinemakers to network with readers through their self-published media, it created, sustained, and, ultimately, archived a vast network of girls and women self-publishing their own minicomics through Dyer’s donations to the Bingham Center.

The Anatomy of the Action Girl Archival System

One of the hallmarks of girl zines—and of zine culture more broadly—is the practice of ‘plugging:’ connecting with other zinemakers by highlighting their work within the pages of your zine, either through reviews, lists, rants or raves. In Notes from Underground, Stephen Duncombe writes that, ‘[e]very zine is a community institution in itself, as each draws links between itself and others.’ [23] For zinemakers, zine communities are knitted together through pages devoted to letters, reviews, and lists. Plugs pages are a mainstay of independent media that Duncombe tracks back to the inception of Amateur Press Associations in America in the early 1800s. [24] Whole zines, like Dyer’s Action Girl Newsletter, are devoted to reviews and information on how to obtain zines by likeminded creators.

As a practice, plugging creates a moveable material ecosystem that networks communities and, most crucially, transforms self-published media into an archival system, preserving the scene in the pages of the zine itself once the community has faded away. As Radway writes, zines ‘involve their users in new social relations … zines produced more zinesters—young girls who suddenly saw the form as something they themselves could create, a rescue from the oppressive local venues of home, high school, and college dorms, which they experienced so often as constraining.’ [25] These ‘new social relations’ and the call to make media oneself is materialised through the plugs page, which, I argue, allows zinemakers to self-reflexively documented the emergence of large bodies of self-published work, archiving a snapshot of an ephemeral community for future readers.

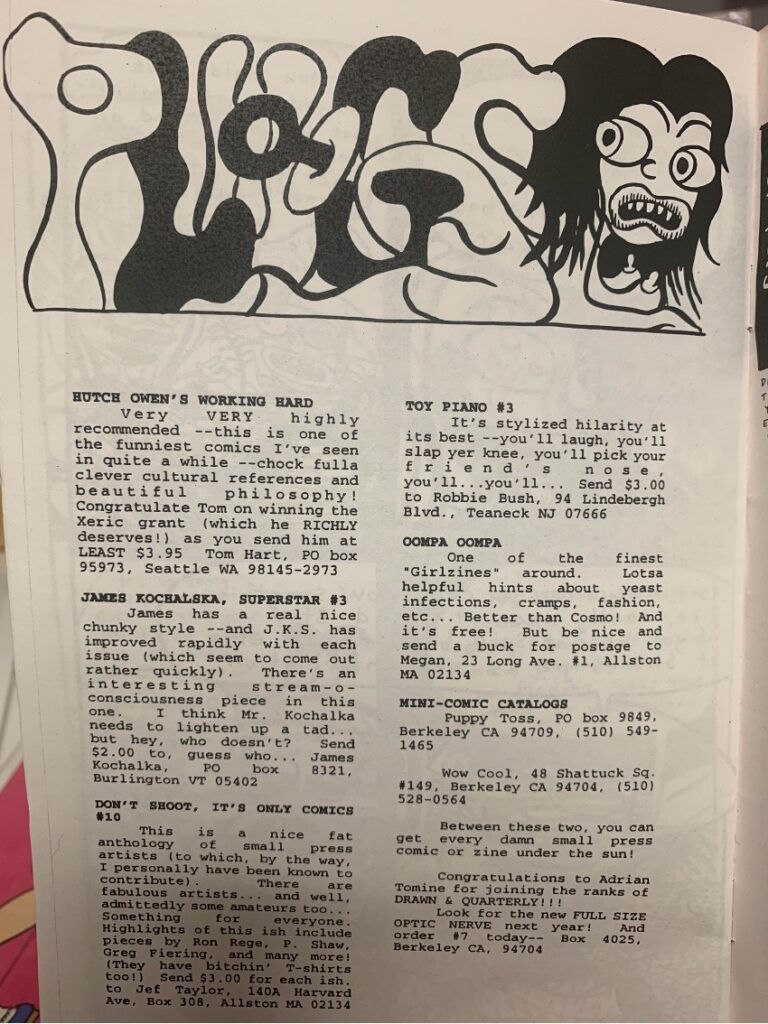

Minicomics produced by girls and women in the 1990s do this same work, but with the intervention of hand-drawn images alongside text afforded by comics, their plugs pages visually model embodied strategies for creating and sustaining community. Action Girl Comics contributor Ariel Bordeaux, for instance, lovingly recorded the comics she was reading in the pages of her self-published mini comic Deep Girl, which ran for five issues, published sporadically between 1993 and 1995. Bordeaux’s recommendations run the gamut from her frequent collaborator Adrian Tomine’s Optic Nerve to fellow Action Girl Comics contributor Megan Kelso’s GirlHero, and Angst Comics by Fawn Gehweiler, who curated one issue of the irreverent all-women comics anthology Off Our Butts, for which Bordeaux drew the cover. In issue three of Deep Girl, Bordeaux christens her plugs page as ‘Plug-A-Ville,’ stylising the title in hairy, bulbous letters that resemble abstract body parts—squirting boobs and butts and an assortment of carnal cavities. In this particular plugs page, Bordeaux redraws in miniature a panel from each comic she plugs, creating an intimate affiliation between the secreting, squirting bodily orifices and the comics she loves and recommends. [26] Issue #4 of Deep Girl doubles down the intimacy of plugging as Bordeaux stylises the sinuous letters of her title around a portrait of a nude woman, rump up, butt plug poking back through the letters spelling out ‘PLUG’ (Figure 1). [27]

Bordeaux renders the act of ‘plugging’ her readers into a network of other comics creators she has read and enjoyed as an intimate, embodied, and, above all, pleasurable experience. In a recent interview, Bordeaux credits the plugs Deep Girl received in other minicomics and review zines like Factsheet Five for helping her find an initial audience for her comics. [28] Like Bordeaux, Dyer also visually celebrates the act of plugging her readers into her girl zine and minicomics network. The cover of her first Action Girl Guide, which collated the first six issues of her review zine, Action Girl Newsletter, for instance, depicts a punk prototype of the Action Girl sitting atop a wave of the work Dyer collates and reviews in the zine’s pages, mouth open, triumphantly spreading the word of the girl zines and minicomics Dyer reviews inside.

Dyer’s desire to plug her readers into this network of other girls creating their own comics and zines did not end with her work on Action Girl Newsletter. She transferred this distinctly third wave ethos of plugging self-published work to the pages of her Action Girl Comics anthology. Furthermore, her Action Girl Manifesto, which appeared in each of her editor’s letters for the comics anthology, encouraged her readers to take action and create their own self-made media outright. Leah Misemer documents how women’s comics anthologies like Wimmen’s Comix have historically sought to mentor and engage their readers as not just consumers but creators, democratising the art of making comics for everyone and not just a select few male masters. Interviewing members of the Wimmen’s Comix collective, Misemer reveals how ‘the editors used a revise and resubmit system to teach women to improve their cartooning craft.’ [29] She writes, that Wimmen’s Comix—and, I would add, the anthologies of marginalised creators that would follow it—‘deserves attention for the way it mobilised serial publication structure to turn readers into comics creators as part of an activist mission to increase the number of women cartoonists working in a male dominated industry.’ [30] But as Dyer herself noted in her Action Girl Newsletter, by the 1990s, when she first undertook her Action Girl Comics project, the collectives of women cartoonists that arose in tandem with the underground comix movement in the 70s had become so solidified as a cohort that few up-and-coming women and girls making comics were afforded access to publication in the pages of established all-women comics anthologies like Wimmen’s Comix. [31] Dyer’s Action Girl Manifesto, then, requests outright what the Wimmen’s Comix editors enacted through their behind-the-scenes editorial process of soliciting comics work from women and making it suitable for publication through internal correspondence between editors and creators. With the proliferation of copy shops across the U.S., as well as the burgeoning third wave girl zinemaking scene, Dyer knew her readers did not have to submit their work for publication in Action Girl Comics to be legitimised or fulfilled as creators. The third wave, DIY ethic that informed Dyer’s all girl comics anthology, then, de-centred the anthology itself as the site through which girls and women found and amplified their voices. Any girl could make her own comic. All she needed was to see other girls like her doing the same.

And many of Dyer’s readers did take up the call and make their own comics, most of which Dyer dutifully reviewed in the back pages of Action Girl Comics. She also meticulously preserved the minicomics that Action Girl readers and contributors sent her—along with the personal correspondence she had with girls and women working at the margins of the comics industry—eventually donating this collection along with her zines to the Bingham Center at Duke.

The core of the Action Girl archival system is encoded in the anthology’s front and back matter, which includes material conventional to comic books—like contributor bios and a letters page—but also borrows from the plugs pages found in zines and self-published minicomics with Dyer’s ‘Action Girl Manifesto’ and her ‘Further Reading’ section, which often spanned two or three pages. Action Girl’s back matter not only opens up a space for Dyer’s readers to correspond with one another, [32] but the contributor bios and ‘Further Reading’ section in the first ten issues [33] include no less than 117 unique citations of minicomics both by Action Girl’s contributors, and readers who sent their work to Dyer over the course of the anthology’s first ten issues. Dyer carefully grafts the conventions of zine circulation into these back pages by including ordering information for each minicomic she reviews or lists from contributors, such as the creator’s address, the price she is requesting for her minicomics, and any special instructions for readers who wished to order from her like including a self-addressed, stamped envelope. In her analysis of the front matter in the early issues of Wimmen’s Comix, Margaret Galvan compellingly suggests that the ‘collaborative illustrations’ through which contributors to that anthology were listed not only ‘conceptualis[e] a distinct way of being together and what community means,’ but also ‘might help us build new methods of better organising this material in archives.’ [34] Whereas Wimmen’s Comix emphasised the collective through these illustrations of contributors together, text-based editorials, and a table of contents, Action Girl Comics manifested Dyer’s third wave call for readers to take action and do-it-themselves by highlighting the efforts of individual creators and making them accessible to readers in a pre-digital age.

While Dyer’s ever-rotating cast of contributors might appear less unified than the collective of women cartoonists represented in the pages of Wimmen’s Comix, Action Girl Comics effectively generates an expansive, diverse, transnational cohort of women and girls self-publishing their own comics, reflexively archiving this work through ‘plugging’ Action Girl readers into this network. Furthermore, by cataloguing these efforts alongside lists of other media Dyer recommends to Action Girl readers, her ‘Further Reading’ section activates what Kate Eichhorn, in writing about Dyer’s actual collection at the Bingham Center, calls ‘archival proximity,’ or the ability of the archive to expand the context in which a text is circulated or received. [35] By situating the self-published work of girls and women alongside a canon of ‘girl friendly’ alternative cartoonists like the Hernandez Brothers, Stan Sakai, and Roberta Gregory, manga by Hayao Miyazaki, the all-women collective CLAMP, and Rumiko Takahashi, the mainstream comics from Marvel and D.C. that Dyer was hunting down from month to month, and even video games available on Dyer’s favorite, ‘most girl-friendly’ [36] gaming platform, Sega Saturn—like Panzer Dragoon Saga, Tomb Raiders, and Shining the Holy Ark, Action Girl—contextualises the growing body of minicomics by girls and women within an expansive catalogue of pop ephemera often culturally reserved for young men who self-identify as ‘nerds.’

Action Girl Comics, then, operates as an archival hub, an access point that ‘plugged’ readers and contributors into a vast, ever-expanding network of women and girls self-publishing their own minicomics. It did this work throughout its seven-year serialization, but, not unlike a zine, Action Girl Comics and its archival system also leads a compelling afterlife, a term I borrow form Radway’s theorization of girl zines, [37] as a counterpart to the Sarah Dyer Zine Collection. In the anthology’s afterlife, Dyer’s citations of minicomics by contributors and readers alike provide a map to the archive of minicomics Dyer preserved in her collection at the Bingham Center.

Most scholarly accounts of Dyer’s zine collection, however, compound the minicomics the collection holds with the collection’s zines without differentiating between the two. Girl zine scholars like Radway [38] and Piepmeier [39] nod to Dyer’s work in comics but do little to distinguish between Dyer as a zinemaker and Dyer as a cartoonist and comics editrix, although, as I pointed out in this essay’s introduction, these roles came with wildly different sets of demands. The lack of recognition of zines and minicomics as similar but distinct modes of third wave media-making is evidenced by the finding aid summary provided by the Bingham Center for Dyer’s collection, which states: ‘Sarah Dyer is the creator of Action Girl Comics, an anthology that she started in 1994 to spotlight the work of women who were self-publishing comics of their own. Prior to starting Action Girl Comics, Dyer was the publisher of Action Girl News, which reviewed women’s and girls’ zines. This collection consists of the zines submitted to her for review.’

Citing Dyer’s work in comics but not specifying that her collection also catalogues the 1990s-era boom in minicomics created by girls and women that Dyer helped instigate and sustain through her all-girl comics anthology, collapses minicomics and zines as one and the same kind of girl-made media, which, as I will argue in more detail in the next section, they are not. Indeed, the Sarah Dyer Zine Collection does not have a full run of Dyer’s Action Girl Comics, which emphasises the archive’s investment in the zines held within the collection versus the collection’s comic books and minicomics. While the collection houses all three distinct kinds of media, by enfolding minicomics into zines, girl zine researchers might unwittingly ignore how minicomics are genetically tied to the lineage of women’s work in comic books specifically and the history of the comics industry broadly. Furthermore, as I investigate in the next section, there are specific strategies that comics can employ that differ from the visual-textual nature of zines, setting the minicomics preserved in Dyer’s archive apart from the zines housed in the collection.

By calling attention to these differences between girl-made minicomics and zines, I do not intend to criticise the Bingham Center or its zine archivists, who work diligently to recover and preserve materials that are so often lost to time. Rather, I mean to call attention to the fact that the growing body of research on the girl wave of minicomics makers in the 1990s remains strikingly underdeveloped given how big a collection this material constitutes even in a single archive. In order to target and understand the scope of the minicomics that live alongside Dyer’s zines in her archive, I utilised the back matter of Action Girl Comics as a map to help navigate hundreds of minicomics self-published by girls and women at the end of the millennium. Cross-referencing the minicomics Dyer reviewed or listed from her contributors in the pages of Action Girl Comics with the holdings at the Bingham Center, I was able to reveal a vast archive of self-published comics living in the shadow of Dyer’s zine collection. Many of these minicomics, like Cookie by Debbie Vasquez, which I will analyse in detail in the next section, cite Dyer’s work in Action Girl Comics as the catalyst for their own comics-making practice, demonstrating the extent to which Dyer’s call to action was, ultimately, successful, even if these materials are passed over or remain hidden in accounts of both the girl zine scene of the 1990s and comics history. Treating minicomics as a medium that is genetically linked to but, ultimately, distinct from zines, in the next section I consider how the ‘ever-expanding network’ [40] of girls and women inspired by Action Girl to make their own minicomics activate key critiques—in particular, as I will explore, a queer of colour critique—of the 1990s’ girl zine movement.

‘Not Like Amy:’ Girl Minicomics & their Queer of Colour Critique of Girl Zines

As I have suggested throughout this essay, although they share much of the same genetic makeup, girl minicomics and girl zines are fundamentally two different kinds of self-published media, despite the fact that they have been largely treated by media scholars, archives, and even artists as one and the same. Noted historian of comics by women, Trina Robbins, for instance, uses ‘zine’ and ‘comic’ interchangeably to refer to minicomics self-published by girls and women in her account of the girl wave of minicomics in the 1990s. ‘Zine art ranges from amazingly excellent to mondo scratcho, but the not-very-good-artists don’t care if their work is crude,’ she writes of the minicomics she surveys, highlighting amateurism as a defining feature of self-published comics. ‘They’re producing illustrated letters, not art galleries to be sent through the mail,’ she concludes. [41] Meanwhile, zine historian Duncombe identifies self-published comics as a sub-genre of zines but not a unique medium in and of itself. [42] In fact, many zines—and girl zines in particular—do incorporate comics or visual elements collaged from comics and cartoons into their pages, from the iconic superhero Wonder Woman to Ernie Bushmiller’s girl troublemaker, Nancy. Likewise, minicomics incorporate certain conventions borrowed from zines such as plugging, which contextualises their work within a larger ecosystem of other self-publishing comics makers. Girl-made minicomics also frequently address a similar set of subject matter as girl zines, including ‘sexual abuse, queer sex, and body-image problems, as well as everyday obsessions and odd tastes.’ In her account of zines’ visual vernacular, however, Radway reveals crucial differences between zines and self-published minicomics. Zinemakers, she writes, ‘practic[ed] an aesthetic that was decidedly not reader-friendly. They produced collaged pamphlets with chaotic, cut-and-paste layouts that defy linear scanning, sometimes resist traditional narrative sequencing, and even refused pagination altogether.’ [43] Comics, by contrast, are, even in their most experimental articulations, decidedly ‘reader-friendly.’ Even the girl wave of Xeroxed and hand-stapled minicomics of the 1990s relies on the conventional syntax of American comics,[44] which privilege traditional narrative structure through sequential, ordered panels separated by gutters that scan left-to-right. Or, as Shiamin Kwa puts it: ‘[c]omics provide a model for reading practices based on continuity, a continuity that is native to the form of comics themselves.’ [45]

If girl zines invite disruption through image-text strategies that resist sequentiality or continuity, girl minicomics model a different way to materialise an inclusive third wave feminist discourse in self-published media. Although Action Girl Comics itself foregrounds its white figurehead as leading the wave of girls making minicomics, the anthology’s archive actually makes accessible a much more diverse cohort of girls and young women self-publishing their comics. Mimi Thi Nguyen laments how in its historicization Riot Grrrl’s fraught engagement with race positions the work of women of colour as ‘an interruption into a singular scene or movement’ as opposed to a ‘co-present scene or movement that conversed and collided with the already-known story, but with alternative investments and forms of critique.’ [46] (187). As Iraya Robles puts it: ‘[w]e are continually narrated and approached, even in retrospect, like we’re a scar or a painful memory for punk feminism—in that story, we ruined it.’ [47] In the Action Girl archives, however, minicomics by queer women and/or women of colour are preserved as an integral part of the larger body of women and girls making comics transnationally. Indeed, as the minicomic I analyse in this section, Cookie demonstrates, girl-made minicomics can generate radical critiques of girl zines without exploiting the life narratives of women of colour or treating their media like ‘a scar’ on the scene.

In what remains of this essay, I read the minicomic series Cookie, self-published by Debbie Vasquez (1995-1999) and preserved in Sarah Dyer’s collection at the Bingham Center, against Tammy Rae Carland’s I (heart) Amy Carter—a near canonical zine that can be found in most zine archives, many scholarly accounts of girl zines, and is accessible to a new generation of readers through its republication in the recent anthology The Riot Grrrl Collection (2013). [48] In contrast to Carland and her zine, neither Cookie nor its creator are widely known. Vasquez created the five issues accessible in Dyer’s zine archive from San Luis, Arizona, which, unlike Washington D.C., Olympia, WA, or New York City, was not a hotbed of activity for third wave feminist media making. Nevertheless, Vasquez’s comics, which follow the phantasmagoric exploits of her eponymous Latina protagonist, testify to how Dyer’s work in Action Girl inspired and sustained Vasquez’s own comics practice, with blurbs from Dyer’s reviews of Cookie printed in the comic’s back pages and correspondence between Vasquez and Dyer preserved in Dyer’s archive. Vasquez even contributed a strip to the final issue of Action Girl Comics, in which Dyer praises Vasquez’s ‘examination of the self-torture we put ourselves through for the guilt and anger we feel.’ [49] Cookie materialises how Action Girl Comics, in its translation of the girl zine-making ethos, ‘knit girls and young women together into far-flung, loosely structured networks.’ [50] Crucially, Cookie also demonstrates how the network of girls and women creating their comics under the aegis of Action Girl activates a radical queer of colour critique of girl zinemaking itself.

‘Not Like Amy’

For five issues published between 1995 and 1999, Debbie Vasquez’s minicomic, Cookie detailed the surrealist slice-of-life misadventures of Cookie, a nihilistic, tattooed, and pierced Latina punk with black and purple hair. As Dyer points out, although Cookie seems to bear the traces of autobiography, Vasquez herself never clarifies if Cookie’s stories are more fact or fiction—a sharp contrast to 1990s-era girl zines, many of which privilege the personal reflections of their authors over forays into fiction. Ngyuen compellingly suggests that the brand of raw, personal disclosure conventional to girl zines capitalises on ‘access and intimacy’ as a means to possess the experiences of women of colour who were marginalised within the scene, asking women of colour ‘to reveal themselves, to bear the burden of representation (“you are here as an example”) and the weight of pedagogy (“teach us about your people”).’ [51] Privileging personal life narrative, girl zines replicate the emphasis on white women’s ‘cathartic, individual psychological acknowledgment of personal prejudice’ as opposed to actionable political work addressing racial injustice, a critique bell hooks files against the Women’s Liberation movement of the 1970s which remains applicable here. [52]

However, girl minicomics of the era—like Cookie—largely eschew straight autobiography. The minicomics by women of colour and/or queer women preserved in Dyer’s collection include Elizabeth Watasin’s Adventures of A-Girl, which narrates the fictional globetrotting of Watasin’s asexual protagonist, A-Girl; Yvonne Mojica’s Bathroom Girls, about a scene-rending tiff between two girl gangs; Paranoiac Gum by Ayu Tomikawa, which contains a selection of short surrealist strips; and Leanne Franson’s long running series Liliane, which includes stories and gags addressing bisexuality and the LGBTQ community. [53] By rejecting memoir, these 1990s-era minicomics by girls and young women not only integrate themselves into a longer history of American comics industry, in which genre fiction was dominant and remains popular even after the rise of the graphic novel in the late 20th century. They also constitute a radical shift in the feminist intervention of third wave, self-published media away from the privileging of white women’s personal experience and their concomitant co-option of women of colour’s life stories, towards the authentic self-expression of women of colour.

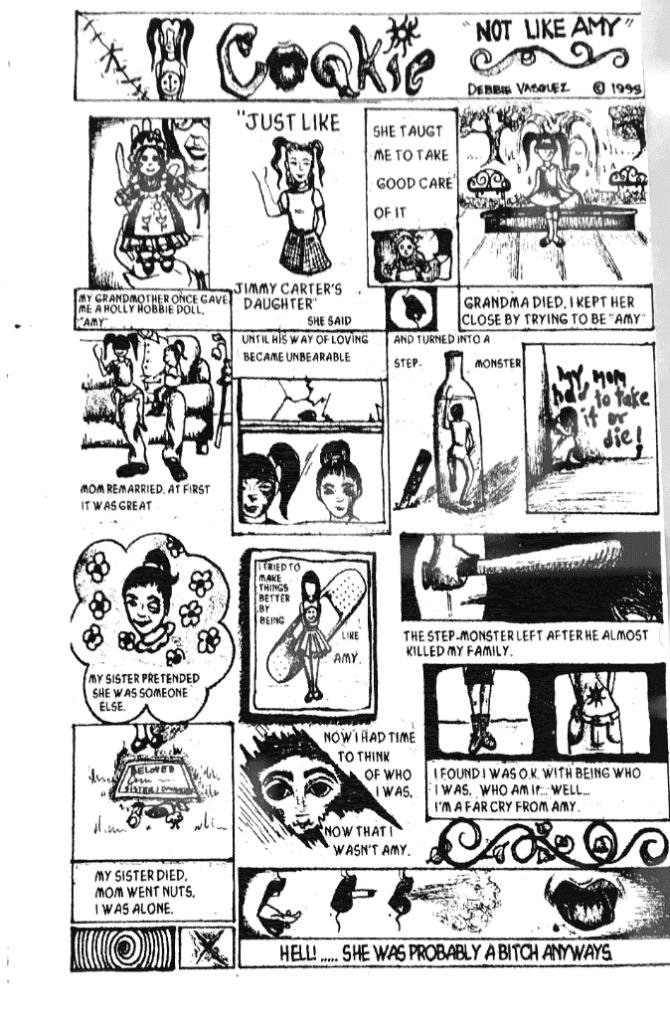

Not unlike the first issues of many superhero comics, the first issue of Cookie tells the origin story of its protagonist in the strip ‘Not Like Amy.’ Amy, it is revealed, refers to Amy Carter, the only daughter of President Jimmy Carter, who came under intense media scrutiny in the late 1970s when she entered the White House as a young girl. As Cookie narrates in ‘Not Like Amy.’ ‘My grandmother once gave me a Holly Hobbie doll, “Amy.” “Just like Jimmy Carter’s daughter,” she said’ (See Figure 2). In a panel depicting Cookie as a young girl, she confesses, ‘Grandma died. I kept her close by trying to be “Amy.”’ Here, Cookie poses in a prim, feminine dress. A black bar covers her eyes, suggesting that her transformation into ‘Amy’ denies Cookie a degree of self-expression. After her grandma’s death, Cookie’s home life descends into chaos at the hands of a ‘step monster,’ who physically and emotionally abuses her, her sister, and their mother. ‘I tried to make things better by being like Amy,’ Cookie narrates in a panel in which she is superimposed against a Band-Aid, once again wearing a feminine dress (this one with a smiley face on it), her face blank in a visual echo of the panel in which she first professes to wanting to be ‘like Amy.’ Playing Amy, is, as this panel suggests, a temporary fix, a Band-Aid, and, most importantly, an erasure of Cookie’s identity. And so, when Cookie’s stepfather nearly destroys her family, her sister dies, and her mom goes ‘nuts,’ Cookie radically breaks away from this persona she has constructed to mitigate the traumatic circumstances of her upbringing. ‘I found I was O.K. with being who I was,’ she states as readers get the first glimpse at her new makeover, which includes combat boots, a low-slung miniskirt, and a tattoo decorating her belly button. ‘Who am I? …Well …I’m a far cry from Amy,’ she continues. ‘Hell! … She was probably a bitch anyways,’ she concludes in a panel that depicts a sequence of four close-ups on Cookie’s lips as she takes sticks out her pierced tongue and takes a long drag on her cigarette.

Cookie’s transformation from trying to be ‘like Amy’ to accepting herself as not like Amy at all not only pushes back against the ‘Amy’ stereotypes embodied by her doll (white, pretty, blonde, prim and proper), but also produces a radical critique of girl zinemaking for which figures like first daughter Amy Carter were exemplary of a new ideal for girls and young women to aspire to. In the first issue of her zine, I (heart) Amy Carter, Carland understands her fascination with the first daughter—what she calls ‘AMY and my commitment to AMYness’—on multiple levels: as ‘my interest/obsession/crush/wanna-be complex.’ She explains that ‘AMY is this sort of icon cuz she turned out to be a politically active geeky girl artist who makes paintings about race and gender and herself.’ [54] Indeed, as Carland reveals through collages of clippings about her, the real Amy Carter was portrayed by the media as a kind of oddball and outsider whose public presence as a child was often politicised even before she became a political activist as a young adult. Not unlike Cookie’s Amy, Carland’s Amy is a fantasy figure onto which Carland can project her own desires as the zine commingles scans of articles about Amy with collages addressing Carland’s views on femininity, sexuality, queerness, and making art. For Carland, Amy constitutes what Sarah Projansky calls an ‘alternative girl,’ who is ‘spectacular … because of [her] difference,’[55] supplying the public with a new set of parameters within which to define girlhood. Carland’s reconfiguration of Amy as a queer subject, an iconic girl subject, and, ultimately, an Other-ed subject carves out a space for young white women who, like Amy, do not ‘fit in’ to envision themselves as alternative, different, and the other, too. In its materialization as a zine, I (heart) Amy Carter allows Carland to frame her own personal interest in Amy as both idiosyncratic and inherently political.

Whether Vasquez was aware of I (heart) Amy Carter or not, her strip ‘Not Like Amy’ inherently rejects Amy Carter as an ‘alternative girl.’ Instead, she reveals Amy to be just another blonde, vacant doll, the shape of which Vasquez’s protagonist tries unsuccessfully to fit herself into. Cookie’s rejection of being ‘like Amy’ and her subsequent embrace of her difference as a queer, Latina punk revises what girlhood can look like through comics that celebrate Cookie’s unique sense of style (combat boots, crop tops, tattoos, piercings, and long flowing skirts) and her playful punk attitude, as they subtly incorporate markers of her heritage, such as the small alters or ofrendas she’s constructed throughout her bedroom.

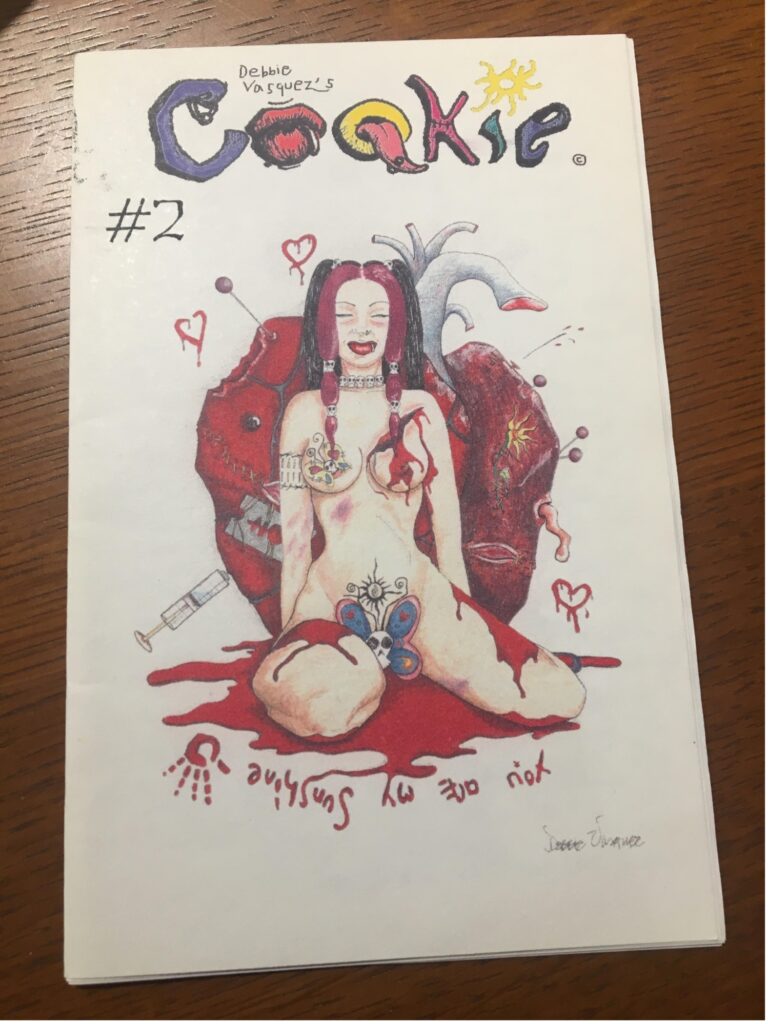

Furthermore, although Vasquez often narrates or alludes to parts of Cookie’s life that are traumatic—such as physical and emotional childhood abuse, self-harm, the abuse of drugs and alcohol, and death [56]—the scars and bruises that she bears from these experiences are framed in a playful, irreverent register that neither exploits nor burdens Cookie with her past. Instead, the fragmentation of Cookie’s body [57] throughout the comic after she rejects being ‘like Amy’ is frequently cathartic, as in the case of the cover of issue #2 on which Cookie is depicted naked, sitting against a backdrop of a bloody heart lanced with razor blades, pins and needles (See Figure 3). The skin above Cookie’s left breast is torn, suggesting that the heart and, perhaps, the content of the minicomic, is torn from her own body. With sugar skulls decorating her hair and tattoos covering her breasts and abdomen, Cookie sits amid the blood leaking from her heart with a plaintive smile on her lips, content now that she has torn her breast her way, on her terms. Refusing to be just another ‘a scar’ upon ‘punk feminism,’ as Robles puts it, Vasquez uses Cookie to serially draw her unique vision of girlhood from the margins, offering readers a critique of the system of girl zinemaking itself, which systematically effaces the narratives of girls and young women of colour through upholding white icons as models for what ‘alternative girls’ might look like. By creating comics that unabashedly embrace a vibrant, messy, irreverent Latina punk, Cookie demonstrates how self-published minicomics combat the positioning of girls and women of colour’s zine- and comics-making as interruptions to or breaks in the larger movement of third wave self-published media.

Coda—Drawn from the Margins: Other Voices, Other Networks

Cookie is just one of the many minicomics preserved in Dyer’s zine archive that testify to how Dyer’s work on Action Girl Comics instigated, sustained, and, ultimately, archived one of the largest bodies of comics work by women and girls in the history of the medium. Amid the boxes that hold Dyer’s collection in the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University are handwritten notes tucked into the pages of girl-made minicomics—missives to Dyer thanking her for giving the artist the inspiration to create and self-publish their own comics. Many more of the minicomics preserved in Dyer’s collection, like Vasquez’s Cookie, cite Dyer or Action Girl Comics in some way, demonstrating how Dyer’s all-girl anthology, although ignored or cast aside in its time, really did draw voices never heard before in the comics industry from the margins to the Xerox machine. Eichhorn argues that Dyer’s collection is valuable because it recontextualises girl zinemaking within the longer lineage of feminist print media preserved at the Bingham Center. She writes that ‘the archive produced new and potentially productive proximities between social agents rarely imagined occupying the same space and time.’ [58] (60-61). While this is certainly true, my approach to Dyer’s archive asserts the material and cultural specificity of a subset of materials—minicomics—that are rarely attended to as distinct from other forms of self-published or amateur feminist media like zines, broadsides, diaries, and manifestos.

By attending to the specificity of minicomics within Dyer’s archive, I have shown how networks of minicomics creators intervene in the third wave landscape of self-published media differently than zinemakers. In the third section of this article, I considered how girl-made minicomics networks create a more hospitable environment for the creation and preservation of comics by girls and women of colour. Not only do these comics offer a critique of girl zines from the era, as I argued with Vasquez’s Cookie, they also visualise new ways of being for girls and young women as well as new possibilities for feminist self-published media. Indeed, Cookie’s own plugs pages come in the form of dedications to Vasquez’s friends, whose portraits are lovingly drawn in the front matter of the last three issues of her minicomic. Just as Dyer dedicated Action Girl Comics to archiving a network of girls and young women earnestly making their own minicomics, Cookie serves as an extension of that archive, opening readers up to other voices and other networks beyond its predecessor. Rather than a closed circuit, girl-made minicomics in the 1990s offer their readers networks nested in networks: an ever-expansive, always-open invitation to do comics themselves.

Acknowledgements

This work was generously supported by a residency at the Queer Zine Archive Project (QZAP) as well as a Mary Lily Research Grant from the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University. Thank you to Kelly Wooten, who provided a great deal of support and guidance while I worked with the Sarah Dyer Zine Collection at the Bingham Center. Thanks, too, to Milo Miller and Chris Wilde, who run QZAP and gave me access to their collection of Action Girl Comics, along with many other wonderful comics anthologies and minicomics created by queer cartoonists. Finally, thanks to my parents and my fiancé for supporting me as I researched, developed, and wrote this piece.

Notes

[1] Action Girl Newsletter #12, Box 8, Folder 2, Sarah Dyer Zine collection, 1985 – 2005, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History & Culture, Rubenstein Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

[2] Alison Piepmeier, Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism (New York: NYU Press, 2009), p. 24.

[3] Sarah Dyer (ed.), Action Girl Comics #1, no. 1 San Jose, CA: Slave Labor Graphics, 1994.

[4] Stephen Duncombe, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, 3rd ed. (Portland: Microcosm Publishing, 2017), p.5.

[5] See Kate Eichhorn, ‘Archival Regeneration: The Zine Collections at the Sallie Bingham Center,’ in The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013), pp. 55-84.

[6] Piepmeier, Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism, p. 45.

[7] In Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, Sara Marcus documents an ‘Unlearning Racism’ workshop lead by an unnamed black woman ‘from the Peace Center’ alongside Riot Grrrl co-founder Kathleen Hanna. ‘This conversation called for a serious switching of gears,’ writes Marcus. ‘The girls had just spent the morning talking about and connecting based on the shared ways they were disadvantages and put down. Now the white girls—which meant a majority of the people there—were being told that they were oppressors as well’ (165). Marcus writes how many of the workshop’s participants were resistant to recognizing their privilege and the whiteness embedded in their movement, a stance which continued to plague not just Riot Grrrl itself but its afterlives in scholarship, as Adela C. Licona compellingly asserts in Zines in Third Space: Radical Cooperation and Borderlands Rhetoric.

See Sara Marcus, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (New York: HarperCollins, 2010); and Adela C. Licona, Zines in Third Space: Radical Cooperation and Borderland Rhetoric (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2012).

[8] Sarah Dyer (ed), Action Girl Comics, no. 1 (1994). San Jose: Slave Labor Graphics, pp. 24.

[9] Janice Radway, ‘Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change,’ PMLA 126, no. 1 (January 2011), pp. 142.

[10] Dyer, Action Girl Comics, No. 1, pp. 1.

[11] For more on the interconnected structure of the mainstream and alternative comic book industries and the multiple collector-driven comic book bubble economies of the 1990s, see the chapters ‘Deathmate (1988-94)’ and ‘The Mailman (1994-2016)’ in Dan Gearino’s Comic Shop: The Retail Mavericks Who Gave Us a New Geek Culture (Athens, OH: Swallow Press, 2017); Gary Groth, ‘Black and White and Dead All Over,’ The Comics Journal, no. 116 (1987): 8; Dirk Deppey, ‘Suicide Club: How Greed and Stupidity Disemboweled the American Comic-Book Industry in the 1990s,’ The Comics Journal, no. 277 (2006): 68–75; and Kristy Valenti, ‘How We Got Here: A Distribution Overview 1996-2019,’ The Comics Journal, no. 303 (February 2019), pp. 120–36.

[12] See Margaret Galvan, ‘Adjacent Genealogies, Alternate Geographies: The Outliers of Underground Comix & World War 3 Illustrated,’ Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society 3, no. 1 (2019), pp. 92–113; Leah Misemer, ‘Serial Critique: The Counterpublic of Wimmen’s Comix,’ Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society 3, no. 1 (2019), pp. 6–26.

[13] Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 81.

[14] Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories, pp. 81-2.

[15] Action Girl Comics Newsletter #11, Box 8, Folder 2, Sarah Dyer Zine collection, 1985 – 2005, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History & Culture, Rubenstein Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

[16] Dyer, Action Girl Newsletter #12.

[17] I discuss the representation of these alienating comic book shop spaces in my analysis of Rachael House’s minicomic Red Hanky Panky (See ‘From the Archive: The Queer Zine Archive Project,’ Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, Fall 2018, Volume 1, Issue 3, 369-389). In my interview with her at the Small Press Expo in 2018, Julie Doucet, whose comic book Dirty Plotte was one of the few single-author comics to be published by an independent comics publishing house in the 1990s, also spoke to the frustrations she faced trying to place her comic book in comics stories and feminist bookstores, both of which labelled her work as pornography. See Julie Doucet, SPX 2018 Panel – Cutting Up: Julie Doucet’s Reinventions from Dirty Plotte to Carpet Sweeper Tales, interview by Rachel Miller, Youtube Video, October 5, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=un8Mxey2oT4.

[18] While Dyer’s strategy should have worked, the plight of Action Girl Comics ultimately illuminated the widespread marginalisation of women’s work in the industry as a whole as animated by their treatment in comic book shops specifically. As she wrote in Action Girl Newsletter #12, publishing the first few issues of her comics anthology had ‘been good and bad.’ She writes, ‘On the bad side it’s teaching me that basically no one cares. The book is doing worse and worse simply because no one cares if you put out something of quality or something interesting. Some shops are racking it with porno books. Some are burying it in a tiny “alternative” section and dooming all the books by shoving it into a back space and not telling anyone about it. Most are not carrying it at all.’ I address how Dyer’s struggles to keep Action Girl Comics stocked and visible in comic book shops relates to the longer history of women’s marginalisation in the field in my book chapter, ‘When Feminism Went to Market: Issues in Feminist Anthology Comics of the 1980s and ’90s,’ (in The Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies, ed. Frederick Luis Aldama [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020], 420–36, 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190917944.013.42). Despite these struggles, however, Action Girl Comics is still one of the longest running comics anthologies of women’s work with 19 issues published over the course of seven years. Comparatively, Wimmen’s Comix published 17 issues over the span of three decades; Twisted Sisters published 5 issues over three decades; and other 1990s-era anthologies that boasted all female identifying contributors like On Our Butts and GirlTalk lasted only for an issue or two.

[19] Hillary L. Chute, Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), p. 1 & 3.

[20] Chute, Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics, pp. 3.

[21] Brigitte Geiger and Margit Hauser, ‘Archiving Feminist Grassroots Media,’ in Feminist Media: Participatory Spaces, Networks and Cultural Citisenship, ed. Elke Zobl and Ricarda Drueke, Critical Media Studies (Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript, 2012), pp. 74.

[22] Red Chidgey, ‘Hand-Made Memories: Remediating Cultural Memory in DIY Feminist Networks,’ in Feminist Media: Participatory Spaces, Networks and Cultural Citisenship, ed. Elke Zobl and Ricarda Drueke, Critical Media Studies (Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript, 2012), 87.

[23] Duncombe, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, pp. 53.

[24] Duncombe, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, pp. 53-4.

[25] Radway, ‘Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change,’, pp. 147-8.

[26] Ariel Bordeaux, ‘Plug-a-Ville,’ Deep Girl, No. 3, 1993, p. 24.

[27] Ariel Bordeaux, ‘Plugs,’ Deep Girl, No. 4, 1994, p. 14.

[28] Ariel Bordeaux, Reflections from the Past: Anna Sellheim Interviews Ariel Bordeaux, interview by Anna Sellheim, February 28, 2020, https://solrad.co/anna-sellheim-interviews-ariel-bordeaux.

[29] Misemer, ‘Serial Critique: The Counterpublic of Wimmen’s Comix,’ p. 8.

[30] Misemer, ‘Serial Critique: The Counterpublic of Wimmen’s Comix,’ p. 12.

[31] Indeed, co-founder of Wimmen’s Comix and vocal ‘herstorian’ of women’s work comics, Trina Robbins writes with a degree of disdain about the self-published comics of the 1990s in From Girls to Grrrlz: A History of Female Comics from Teens to Zines. These comics, she asserts, are often in the ‘mildly depressing autobiographical genre’ (127). She praises one minicomic by Ellen Forney as significant because ‘no one gets abused, raped, or permanently robbed of their self-esteem by rotten parents.’ See, Trina Robbins, From Girls to Grrrlz: A History of Female Comics from Teens to Zines (San Francisco: Chroncile Books, 1999), p. 127.

[32] Misemer argues that serialised comics anthologies like Wimmen’s Comics and Action Girl Comics model a feminist iteration of what she calls comics’ ‘correspondence zone.’ This delineates how different parts of a comic book serial, like letters pages or contributor bios, elicit public dialogue between readers activating the readership as a community (Misemer, ‘Serial Critique: The Counterpublic of Wimmen’s Comix,’ 9-10). This is certainly the case for Action Girl Comics, as readers sent Dyer photographs of themselves, fan art, letters, and their own minicomics. Here, I focus on how this particular correspondence zone is inflected by third wave energies in order to not only build and sustain a community of readers, but also to materialise an archive of self-published work by girls and women, the scale of which is larger than any body of work by women in comics previous to this moment.

[33] There were nineteen issues of Action Girl Comics published altogether, but not even Dyer’s own collection at the Bingham Center has a complete run of her all-girl comics anthology. I acquired my issues through fellow collectors and eBay, but gaps still remain in my collection. Even though Dyer reviewed minicomics sent to her by contributors and readers in each issue, I chose to base this number off the first ten issues, which I have a nearly complete run of. This count excludes issue #5, which I did not have access to at the time.

[34] Margaret Galvan, ‘Archiving Wimmen: Collectives, Networks, and Comix,’ Australian Feminist Studies 32, No. 91-92 (2017), pp. 32 & 31.

[35] Eichhorn, ‘Archival Regeneration: The Zine Collections at the Sallie Bingham Center,’ p. 61.

[36] Action Girl Comics #9, p. 24

[37] Radway expands the scholarly perception of zines as ephemeral texts that ‘enjo[y] only brief half-lives.’ She elaborates on zines’ multiple, interlocking afterlives that are the ‘result of the actions of a significant number of former zinesters who were profoundly changed by their zine-ing’ and ‘developed a commitment to extending the reach and effects of zines into the future’ through archiving them institutionally and via grassroots methods (See, Radway, “Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change’, pp. 143-44).

[38] Radway, “Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change,”p. 145.

[39] Piepmeier, Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism, p. 46.

[40] Radway, ‘Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change,’ p. 148.

[41] Robbins, From Girls to Grrrlz: A History of Female Comics from Teens to Zines, p. 129-30.

[42] Duncombe, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, p. 13-4.

[43] Radway, ‘Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change,’ p. 141.

[44] The visual conventions of comics have been well-documented in comics scholarship. Many comics scholars cite these conventions as established by Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics [New York: William Morrow Paperbacks, 1994]).

[45] Shiamin Kwa, Regarding Frames: Thinking with Comics in the Twenty-First Century (New York: RIT Press, 2020), p. xxii.

[46] Mimi Thi Nguyen, ‘Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival,’ Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 22, No. 2-3 (November 2012), p. 187.

[47] Iraya Robles as quoted in Nguyen, ‘Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival,’ p. 187.

[48] Lisa Darms, ed., The Riot Grrrl Collection (New York: The Feminist Press, 2013), pp. 101-120.

[49] Sarah Dyer, ed., Action Girl Comics #19 (San Jose, CA: Slave Labor Graphics, 2000), p,23.

[50] Radway, ‘Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change’, p. 148.

[51] Nguyen, ‘Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival’, pp. 185, & 180.

[52] bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 3rd Edition (London: Routledge, 2014), pp. 55-6.

[53] It’s worth noting that Franson is the only white queer woman included in this short survey.

[54] Darms, The Riot Grrrl Collection, p. 104.

[55] Sarah Projansky, Spectacular Girls: Media Fascination & Celebrity Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2014), pp. 64-5.

[56] All of which, as Eichhorn points out, are conventional topics of girl zines from the era—particularly ‘graphic retellings of ritualised forms of self-abuse and body modification,’ which we see in Cookie (Eichhorn, ‘Archival Regeneration: The Zine Collections at the Sallie Bingham Center,’ 81).

[57] In her award-winning presentation, ‘The Fragmentary Body: Traumatic Configurations in Autobiographical Comics by Women of Colour,’ Francesca Lyn reveals the longstanding trope within comics life writing by women of colour of visually fragmenting the body, an optic that is certainly present in Cookie, although it is not autobiographical. Lyn’s theorisation of visualising the experiences of women of colour through ‘fragmentary body’ might also be productively applied to girl zinemaking with its aesthetics of cutting up mainstream material media representations of girls and young women for collage. See, Francesca Lyn, ‘The Fragmentary Body: Traumatic Configurations in Autobiographical Comics by Women of Colour’ (International Comics Art Forum, 2019).

[58] Eichhorn, ‘Archival Regeneration: The Zine Collections at the Sallie Bingham Center,’ pp. 60-1.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey