Digital Violence: A Symposium

by: Hannah Hamad , April 5, 2018

by: Hannah Hamad , April 5, 2018

‘Digital Violence: A Symposium’ took place on 4th November 2017 at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) in Cambridge. It gathered an impressive collection of scholars based in the UK, Ireland and the US. They came from across the spectrum of disciplines, such as film, media and cultural studies. Each spoke to an aspect of the wide-ranging, ever-changing and manifestly urgent matter of digital violence. The bleakness of the late autumn weather in Cambridge that day fitted the topic of the symposium rather well. Digital violence can be a difficult, exhausting and traumatic subject. Nevertheless, it is an omnipresent facet of the everyday life we increasingly experience as we participate in online networks and communities. This only draws a line under the timeliness of this event and the talks that comprised it.

The day was organised and hosted by Tanya Horeck and Tina Kendall. Both are members of the Department of English and Media at ARU and key scholars in the fields of feminism and digital media studies. They have played respectively important roles in shaping academic understandings of feminism in digital environments: Horeck via her well-known work on mediations of rape (see, for example, Horeck 2004) and Kendall through her research on violence in cinema. Notably, in 2011, they collaborated as editors of The New Extreme in Cinema: From France to Europe, one of the ground-breaking books that set the direction for debates on the contemporary cinematic representations of sexual violence. The two keynotes and three panels that followed differently addressed some of the many issues and debates about gender, race and their intersections that arise from the charged topic of digital violence.

Among other points, three key themes emerged as recurring issues and topics for discussion over the course of that November day in Cambridge. The first was digital feminist activism encompassing hashtag feminism and the various social media campaigns that had appeared online in the lead up to the symposium. The second theme evolved around digital intersections of gender and race. Last but not least, the participants in the symposium discussed toxic masculinities, digital male or masculine violence and rape cultures.

As Kendall explained in her terrain-mapping introduction to the day, the starting point for the symposium was to explore how encounters with violence in the twenty-first century have been impacted by an interface culture that encourages us to like and share digital media content. Suggesting that we have reached the point that hardly a day goes by without an example of gendered/racialised/sexual violence in ‘the digital mundane’, Kendall was quick to highlight that the relationship between violence and digitality is a close one. She also emphasised that the processes that sustain these cultures of violence are both complex and obscure. Many following speakers expressed similar views that had been confirmed by their research findings.

Digital intersections of gender and race were covered in an outstanding opening keynote speech on digital violence and white spectatorship, which was delivered by Caetlin Benson-Allott from Georgetown University in Washington DC. The underpinning concern in her talk ‘Whose Horror?’ was anchored by an on-point reading of Jordan Peele’s recent film Get Out (2017). The message of this horror, she explicitly stated, was that black people are not safe in white neighbourhoods. She further argued that race remained a defining boundary of social inclusion and exclusion in both American society and media and so the film could contribute to the proliferation of anti-black violence in social media in the US.

Arguing a range of related points, to the effect that anti-racist social media protests are failing to generate action, that digital platforms in fact perpetuate racism, and that the regimes which govern digital violence are themselves racist, Benson-Allott invoked the case of the role played by Facebook Live in the mediation of the fatal police shooting in 2016 of African American Philando Castile, about which she has written elsewhere. (Benson-Allott 2016). She argued that a video of his death broadcast live on social media by his female partner Diamond Reynolds—reveals some of the limits of sociality and liveness that challenge Facebook’s narrative of community. This, she continued, facilitates an empathic but ultimately facile spectatorship of suffering. It transposes activism into a spectatorial history of such suffering.

If the first keynote focussed on the racial context of digital violence, a number of talks in the ensuing panels dealt with the topic of digital feminist activism, primarily as it interacts with rape culture. Symposium co-organiser Tanya Horeck raised one of the most urgent topics of the day in her talk on what she described as ‘public rape’ in the digital age. She addressed the networked affect produced by the online circulation of digital violence—specifically sexual violence against women by men. A remarkable media phenomenon she pointed to that pertained ‘public rape’, and its online circulation was the emergence of a cluster of films she described as ‘a new breed of transmedia documentaries intended to facilitate public discussion about these issues.’ Although Horeck mentioned campus rape culture exposé The Hunting Ground (Kirby Dick, 2015) among her examples, she mostly focussed on the Netflix documentary Audrie & Daisy (Bonnie Cohen and Jon Shenk, 2016). As she claimed, this film reconstructed rape through the affectivity of the social media interface.

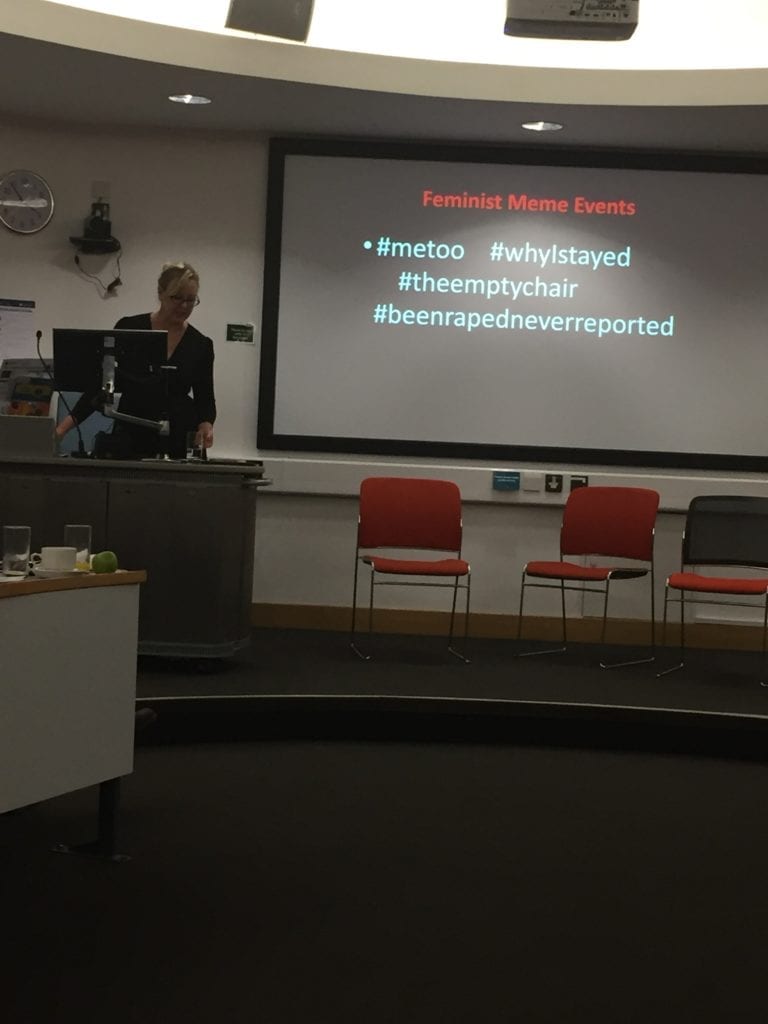

In her paper, Horeck referred to a wide range of pertinent and related issues concerning the phenomenon of ‘public rape’, spanning the frivolous social media documentation by perpetrators and onlookers of the Steubenville, Ohio gang rape of a high-school girl by a group of her male peers, and the Harvey Weinstein scandal and subsequent virality of the #MeToo hashtag that was prompted by a tweet from actress Alyssa Milano. Because of the absence of putative legal consequences for celebrities who rape, and more broadly the Internet’s toxic techno-culture, abuse of women is, Horeck stated, both normalised and endemic. The concept behind the term ‘public rape’ has thus taken on new significance in today’s online era and in the digital networked culture that we live in. Posing a question about what has changed with the shift to digital culture, Horeck was emphatic that it is not just the content of rape culture that has shifted, but the forms and modes of transmission. ‘The sheer speed’ by which images are now able to be recontextualised and recirculated has been paradigm-shifting.

Fig. 1. Symposium co-organiser Tanya Horeck on some of the ‘feminist meme events’ enabled by digital culture

With her talk on digital feminist activism in Peru, Sarah Barrow from the University of East Anglia made an outstanding contribution to the coverage and scope of the symposium by moving the discussion about digital violence beyond the bounds of the Anglophone world. She shone a light on the fascinating case of feminist activism that emerged on the back of the decision by Miss Peru 2018 beauty pageant contestant Camila Canicoba who used the opportunity of having her nation’s—and subsequently the world’s—media attention turn to her to make a feminist intervention into rape culture and violent misogyny in Peru. Notwithstanding that Barrow’s concluding remark pointed to the fact that the ‘radical potential of digital culture for feminism is yet to be realised,’ she commented on a number of instances in which digital media have been used in attempts to disrupt the gender status quo in Latin America. Her presentation offered a fascinating exploration into experiences of sexual harassment and violent misogyny and the ways in which Latin American women have been responding to it by using digital media.

Following Barrow, Helen Wood from the University of Leicester presented her case study on the brief celebrity standing of a young woman who came to be known as The Magaluf Girl. The talk referred to public sex, virality and the class relations of social contagions. This celebrity, Wood explained, arose from a fleeting period of intense media attention that came as a result of online virality. It ensued from uploaded video documentation of the woman’s participation in a disingenuous nightclub competition that offered her a ‘holiday,’ which turned out to be the name of a cocktail, in exchange for her public performance of oral sex on twenty-four men. Wood contextualised this incident explaining the relations that exist between the working class and the attainment of reality celebrity. As she stressed, affective class relations gave the story of Magaluf Girl its tempo.

Acknowledging that metaphors of disease and contagion are often used to describe the digital world (i.e. ‘going viral’), Wood made it clear that the reason why the case of Magaluf Girl is troubling is because there exists a longer history of contagion as a metaphor for the working class and working class women have long been signified as carriers of dirt and disease. She emphasised that this was not a set of transformations that had been engendered by spreadable technology. Rather, the digital environment has enabled amplified repetition of them, particularly in relation to vulnerable girls with no access to victim status. She went on to discuss the ambivalences of broader postfeminist sexual freedoms that exist in a context where sexual behaviours are nonetheless vigilantly policed, concluding that click-bait media coverage intensified the figure of Magaluf Girl at her expense. It was her hyper-visibility in spheres of digital media that ultimately silenced her.

Elaborating further on contemporary rape culture, Despoina Mantziari spoke about the continuities between cinema and online media with respect to the practice of media rape – something she terms ‘sadistic scopophilia’ – especially with regard to the 2010 feature film, a remake of the 1978 progenitor, I Spit on Your Grave. Invoking work by Claire Henry (2014), Mantziari situated the remake as part of a reboot of the rape-revenge genre. She also pointed to recent rape-revenge films like Elle (Paul Verhoeven, 2016) and In-Between (Maysaloun Hamoud, 2016), as well as rape-revenge themed television series, including Top of the Lake (2013-) and The Handmaid’s Tale (2017-). Speaking to issues around cinematic pleasure and lack of consent, repurposing of technologies and so-called ‘creep shots’, Mantziari argued that digital technology enabled sadistic scopophilia to seep from the imaginary to the real and posed questions about how changes in copyright law could impact on issues of consent and media rape.

Moving the focus of discussion to digital intersections of gender and race as well as intersectional approaches to interrogating digital violence, Sarah Anne Dunne from University College Dublin addressed some of the issues that arise from such intersections. Presenting findings from her research on misogyny, race and anti-feminist rhetoric in online discourse pertaining to the allegations of sexual violence made against US media icon Bill Cosby, Dunne’s starting point was to explore, via her case study, how rape culture proliferates and is supported in digital networks. This involved engaging with rape myths, what she referred to as ‘the building blocks of a rape culture’ that operate to discredit and damage victims. Then Dunne discussed rape myths and race, specifically the cultural bogeyman figure of the black male rapist of white women, linking him to the culture of lynching in post-slavery America. In doing so, she mentioned the notorious case of Emmett Till, the fourteen-year-old African American boy who in 1955 was brutally murdered in a racist revenge attack after he had allegedly whistled at a white woman. Thereafter, Dunne discussed Susan Brownmiller’s now equally notorious writing about the Till case in her 1970s book on rape culture of the time Against Our Will (1975), which has been viewed by some as borderline apologism for the boy’s murder and the acquittal of his killers on ostensibly (white) feminist grounds. Since that time, Dunne contended, racial profiling is reported to be at an all-time high. In this context, Dunne situated her research about online discourse on the Cosby allegations. Dunne argued that historical intersections of race, gender and sexuality from the 1970s onwards continue to negatively impact on and undermine feminist politics. With respect to her case study, analysis of her data set (Tweets about the Cosby allegations from February 2017) confirmed that misogynistic dogma was reaffirmed through defence of Cosby’s position. There was a noteworthy correlation between misogynist discourse and manifestations of rape culture.

A number of speakers over the course of the day also dealt with different issues arising from the connected topics of toxic masculinities and digital cultures of masculinity and/or violence. Lindsay Steenberg delivered a talk on violence, masculinity and what she terms ‘digital classicism.’ Taking the millennial blockbuster historical epic Gladiator (Ridley Scott, 2000) as her central case study, Steenberg demonstrated the importance of digitality to the aesthetics and mentality of contemporary sword and sandal films. As she showed, digitality slows time down through combat, and ‘digital classicism’ takes the gladiator out of the past to project him into the future while remaining committed to notions of a pre-feminist past.

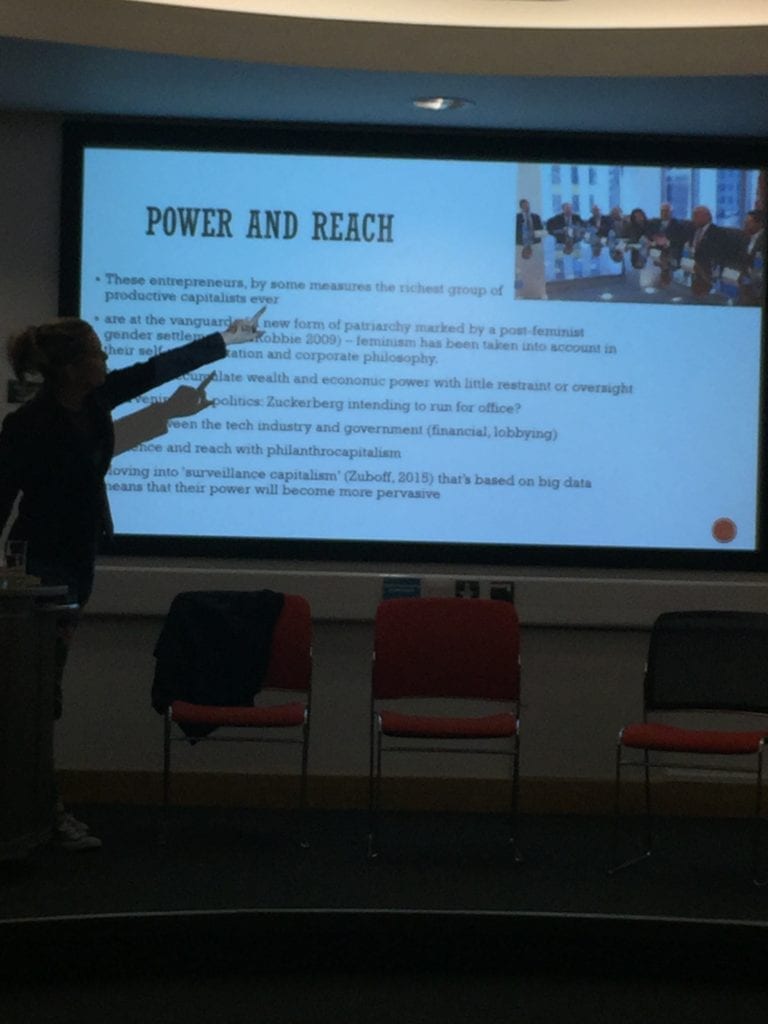

Continuing the thread on masculinity and digital culture, Alison Winch presented a set of initial thoughts and findings from what promises to be a significant new research project carried out in collaboration with her University of East Anglia colleague, Ben Little. Winch raised the global stakes of the discussion in her illuminating and alarming talk on the men she usefully terms ‘The New Patriarchs of Digital Capitalism’ and the patriarchal politics which, she argued, characterise their respective practices of ‘philanthro-capitalism.’ The project, Winch explained, ‘investigates the social, cultural, economic and political significance of key figures (mostly male) in the tech industry’, such as, for example, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, and Peter Thiel of Paypal. The researchers ask questions about these figures’ behaviour and practices and how they secure their personal power. Seeing their rise to social, cultural and political prominence and influence as symptomatic of how ‘patriarchy is reformulating itself’, Winch and Little seek to explore how these men ‘exploit and extend hierarchical power and coercive authority.’

Fig. 2. Alison Winch of the University of East Anglia speaks to the ‘power and reach’ of the tech industries’ philanthro-capitalists

Presenting the closing keynote on behalf of herself and her co-author Eugenia Siapera, Debbie Ging of Dublin City University concluded the day by speaking at length to some of the conceptual paradoxes and material realities that must be dealt with when negotiating and navigating today’s politics of digital violence. Mapping the terrain of what constitutes digital violence, Ging (and Siapera) noted trolling and flaming, incitements to hatred and violence, cyberbullying, and online misogyny and racism as just some of its many manifestations. Talking about the issue of nude imagery online, they emphasised a key problem with regard to dealing with this issue around the inadequacy of existing legislation, and the fact that one wins court cases on a basis that doesn’t address the misogyny of the act. Posing the question of whether platform governance can or should provide the solution to this problem, the authors highlighted that online hate triggers interaction and traffic and therefore reverence for the digital media platforms. In their remarks on the gendered hierarchy of online media platforms from 4chan through Tumblr, they made manifest the problematic extent to which violent misogyny is treated as ludic and/or with jocularity by users—a problem that they aptly described as ‘the gamification of digital violence.’

REFERENCES

Benson-Allott, Caetlin (2016), ‘Learning from horror’. Film Quarterly. Vol. 70, No. 2, pp. 58-62.

Brownmiller, Susan (1975), Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, New York: Bantam Books.

Henry, Claire (2014), Revisionist Rape-Revenge: Redefining a Film Genre, Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Horeck, Tanya (2004), Public Rape: Representing Violence in Fiction and Film, New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

Horeck, Tanya and Tina Kendall (eds.) (2011), The New Extremism in Cinema: From France to Europe, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey