Deviant Women: Embodied Archives, Living Documents

by: Aylwyn Walsh & Fenia Kotsopoulou , October 5, 2020

by: Aylwyn Walsh & Fenia Kotsopoulou , October 5, 2020

Somewhere between narcissism and a visual joke, she plays with the teasing look we know so well from glossy magazines. She positions her body so that its fleshy promises are offered for consumption. Her seriousness helps the sales pitch. She is an advertisement for strong women. Glamorous, haughty, beautiful and secure at leisure and in the boardroom.

Working with self-portraits and live performances for the camera, Fenia Kotsopoulou curated her original visual project, ‘What Beauty Feels Like’. She co-created it with her collaborator, Daz Disley. Fenia’s statement reads:

‘What Beauty Feels Like’ is the marketing slogan of a popular hair removal product. It persuades the audience to believe that they will be ‘beautiful’ as long as they remove body hair for touchable, soft, desirable, extra smooth, moisturised and shiny legs that they can proudly show off.

I use the same slogan to celebrate:

- The pleasure of ‘failing’ to conform to certain presumptions about female appearance.

- The pleasure of ‘failing’ to satisfy basic expectations of female presentation and image.

- The pleasure of ‘failing’ to follow social standards of beauty.

- The pleasure of showing off real hairy legs—touchable, soft, desirable, moisturised, shiny and beautiful.

In the photo series, Fenia reversed time to offer an assemblage of hyper-femininity performed against her hairy dancer’s legs. She recalls that at exhibitions many viewers approached her to find out if these were ‘her’ legs, as if, in their excessive hairiness, they couldn’t belong to her.

In her performance of the desirable body, Fenia’s hairy legs become appendages that exceed the woman. They are an extra—augmenting her own bodily limits in the manner of a ventriloquist’s puppet, or the wilful dancing child whose legs dance her to death, as discussed by Sara Ahmed. (2014 & 2017)

Using Fenia’s visual work as a starting point, we (Fenia and Aylwyn) partnered to commence a creative collaborative project to produce different discursive meditations on women’s bodies. From different disciplinary perspectives, we aimed to concentrate on the slippage between what is lived and the cultural representations of women and their supposed ‘deviance’.

In this hybrid visual performance essay, we offer a performative dialogue that engages with photographic documentation of female bodies—in particular when women are judged to be unruly, or deviant. By excavating the possibilities of disciplinary practices in photography and performance, we consider how archival documentation of women’s ‘deviance’ reveals anxieties, shame and judgment in terms of patriarchal norms. As feminist cultural analyses have demonstrated, this often results in an inevitable desire to contain, limit or restrain women in the institutions upheld by patriarchy. (Faith 2011)

If deviance is the cause, then shame, anxiety and hysterical affects are the symptoms making women legible as ‘other’. (Appignanesi 2007; Didi-Huberman 2003 & Hustvedt 2011) In our investigation of the patriarchal acts to quell such affects, as well as the women themselves, we use our feminist sensibility. We deliberately disrupt some of the conventions of academia by drawing attention to the problems of evidence—one of the central classic tenets of excellent science. Historically, scientific evidence has been used to justify criminalisation of whole population demographics and to support racial profiling. Its most lethal consequences have been the basis of eugenics. (Crimp 2005 & Puar 2017)

As scholars and creative practitioners, when we travel between examples and historical eras, we position ourselves amongst these arguments: deliberately provocative, attempting to foreground the slippage of the artist’s voice into the scholarly realm. In this sense, we are influenced by Saidiya Hartman’s methodology of excavating archives in pursuit of recovering insurgent, wayward women as a counter narrative to the lives that have been documented through surveillance. (2019) In her moving work, Hartman mines visual remnants from archives to consider what stories are as yet untold about the women she finds in archives, then weaves narratives that unpick the ways their images have been fixed to waywardness: unruliness, criminality and pathology. (2019) Considering one of the images she found, Hartman comments:

The singular life of this particular girl becomes interwoven with those of other young women who crossed her path [or] shared her circumstances … Without a name, there is the risk that she might never escape the oblivion that is the fate of minor lives and be condemned to the pose for the rest of her existence, remaining a meagre figure appended to the story of a great man. (2019: 25; italics added by the authors of this article)

Photography then provides the evidentiary opportunity to reinvigorate the stories of objectification beyond its era. As Hartman insists, there is much to be gained from refusing oblivion and resisting closure. Her work seeks the recuperation of specificity. For the black young women she profiles, narrative and embodied experience become fundamental to their recognition as human. Drawing on Hartman’s conclusions, our approach turns on to the production and reproduction of gender norms through phallocentric optics.

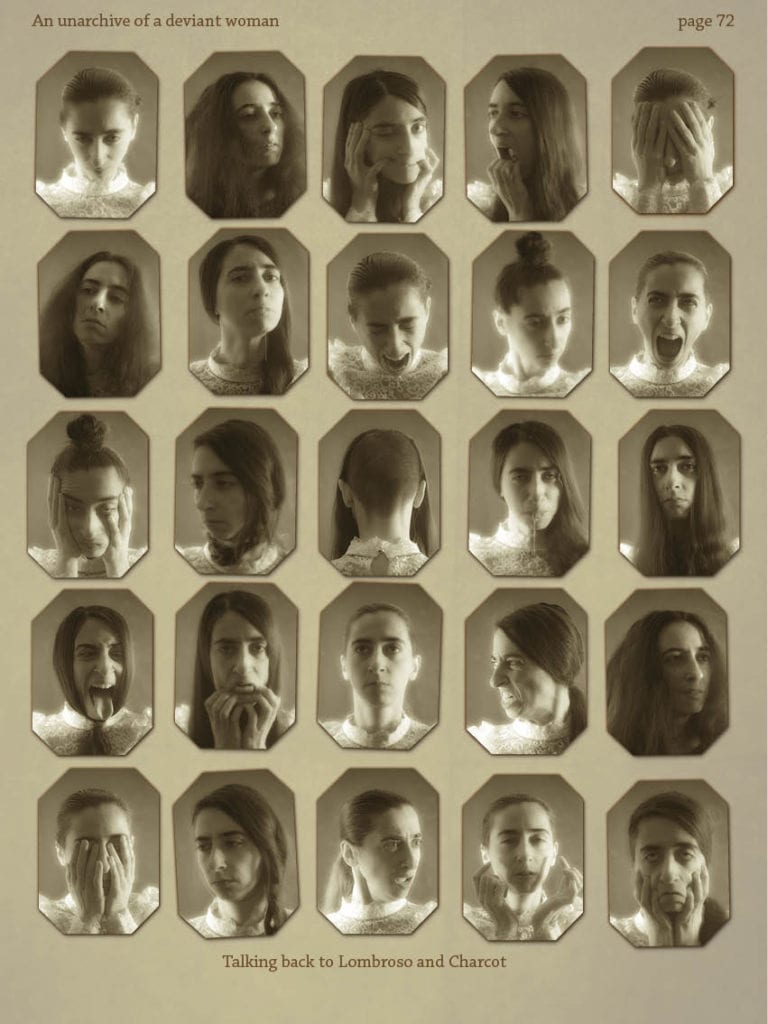

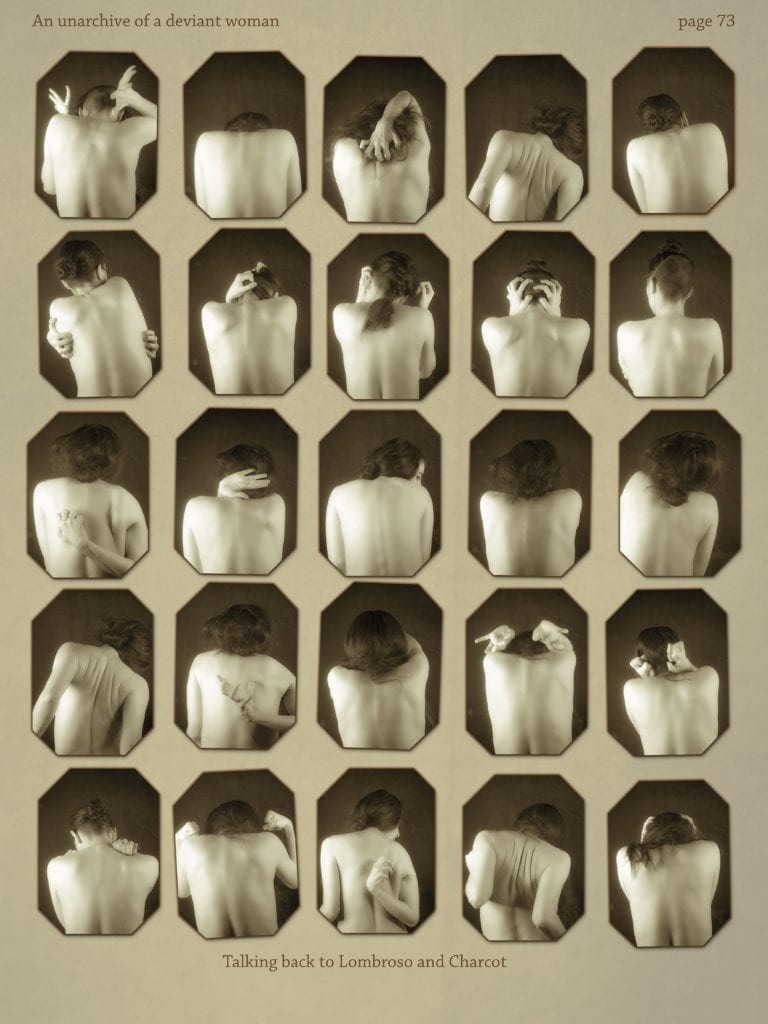

While live art (Fenia) and performance (Aylwyn) are disciplinary playgrounds, we will be looking at the photograph as a medium that produces conflict, and does not merely represent it. [1] We offer a conceptualisation of visual cultures in two directions. At first, we revisit a culture forged through photography as evidence in the documentation of hysteria and other ‘female’ problems in early psychoanalytic work during the nineteenth century, notably undertaken by Jean Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière asylum. These were closely related to the early criminological work of Cesare Lombroso and his daughter Gina Ferrero who documented typologies of criminality, resulting in a significant theorisation of delinquency in women in La Donna Delinquente (1895).

Then, we move towards a feminist re-visitation of these articulations of deviance through visual cultures in the original photographic works in Kotsopoulou’s ‘Deviant Women’ sequence. We propose that this enables a recuperation of ‘deviance’ from a shameful stance that determines possibilities, allowing to foreground the value of self-representation beyond gendered norms.

Visual Cultures of Deviance

There is a long history of feminist critique of gendered norms and the values ascribed to maintaining or defying such norms. (Ahmed 2000; Baer 1994; Harpin 2018; Horn 1995) With the imagery of Fenia’s hairy legs in mind, we began to wonder about the significance of the legs as ‘not-me’, or as ‘other’. What might it mean to conceive of these non-conforming legs as ‘prosthetic’? (Garoian 2008 & 2013) [2] To this end, we are most indebted to Sara Ahmed and her theorisation of ‘becoming strange’. (2000) [3] This performance for camera enables the recognition of the stranger, in Ahmed’s terms:

such that the stranger becomes recognised as the body out of place. Through such strange encounters, bodies are both de-formed and re-formed, they take form through and against other bodily forms. (2000: 39)

Where Fenia’s strange, hairy limbs intrude into the image, they remind us that there is no singular identity to ‘woman’ and no simple ideal to capture in photography. Her sequence points to this erosion of singular understandings of beauty or ‘the (female) body’—and this seems to occur at the level of the skin. The camera’s focus on body hair and her refusal to comply with normative rules keeps attention at this surface of the body. Despite the figure’s pride, we return again and again to imagine such pride working in opposition to shame. For Ahmed,

if the skin is a border, then it is a border that feels … the skin, ‘as the outer covering of the material body’, is where the intensity of emotions such as shame are registered. (Jennifer Biddle 1997: 228, cited in Ahmed 2000: 52)

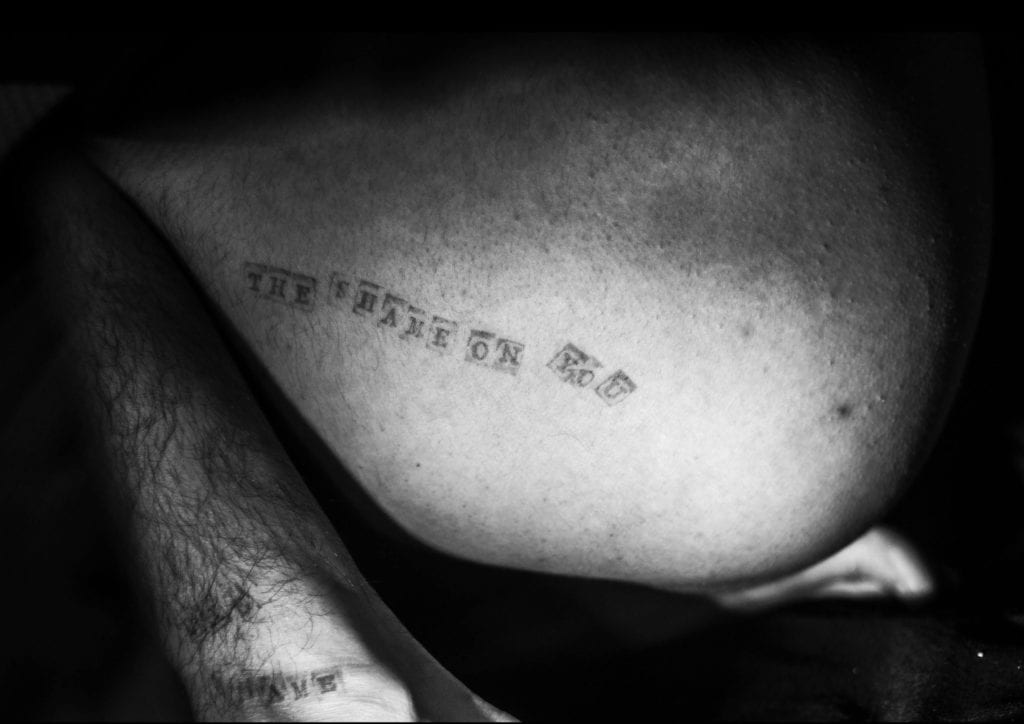

Shame: Not only being marked by a blush or a pinching of the eyes. Shame speaks at the corner of the mouth. Shame, as the nefarious lover of photography. It is waiting to be blinked at and developed as we seek to smoothe out how we are seen, by learning to perform how our bodies must appear. [4]

Here we are thinking with performance studies scholar, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and others about excess and shame. Sedgwick says:

shame effaces itself; shame points and projects; shame turns itself skin side out; shame and pride, shame and dignity, shame and self-display, shame and exhibitionism are different interlinings of the same glove. Shame, it might finally be said, transformational shame, is performance. (Sedgwick 2003: 38)

On Photography, Evidence, and the Problem of Legibility

Having commenced with a feminist approach to discussing Fenia’s self-portraits, we then embarked on a collaborative consideration of how photography, evidence and the problems of legibility have been bound up with the (deviant) female body. To this end, visual criminologist Eamonn Carrabine states:

Ever since the birth of the camera it has been accused of upsetting the divide between public worlds and private selves, transforming the very act of looking and giving rise to a whole series of characterizations of this condition: the society of spectacle, the politics of representation, the gendered gaze and so forth, are among the more well known. (2014: 134-5)

In the field of cultural criminology, Jeff Ferrell & Cécile van de Voorde discuss:

the documentary photograph is neither the objective reproduction of an external reality nor a subjective construction of the photographer, but rather a visual documentation of the relationship between photographer, photographic subject, and the larger orbits of meaning they both occupy. The reality that such a photograph captures is not that of the people in front of the lens, nor that of the photographer, but of the shared cultural meanings created between photographer and those photographed in a particular context. (2010: 41)

Such description puts forward the photograph as a locus of cultural values that are produced through how certain bodies are seen, understood, and formed via replication of images. This understanding has been considered in feminist analyses but also takes a social justice dimension. For instance, in the West, the present day attachment of criminalised identities to certain tropes of blackness, images are used to justify state violence. (Mirzoeff 2016 & 2017) Considering the body and its symbols, cultural theorist Mimi Nguyen discusses how these are produced by the kinds of racialised optics that equate a ‘hoodie’ with the freight of criminal objectification (2015). The photograph produces and replicates the subjection of difference, deviance or danger when it does not undo the perspectives that marginalise, fetishise or objectify. Carrabine, referring to the use of photography in criminological history, writes that ‘photography was a vital element in the construction of the modern criminal subject’. (2014: 134) He goes on to examine ‘how the dynamics of celebrity, criminality, desire, fame, trauma and voyeurism continue to shape social practices in significant and often disruptive ways’. (2014: 134-5)

In this view, photography does not simply capture the social practice, but produces certain epistemological relations between the subject and the viewer. For Henne and Shah (2016), this signals the significance of a feminist approach to visual criminology as we ‘query gendered power relationships embedded in the images of crime, deviance, and culture.’ (2016: 1)

In the nineteenth century, women incarcerated in prisons and asylums served as fitting subjects for experimental treatments and documentation of their outcomes; most notably in the work of Charcot, Lombroso and Ferrero. (Didi-Huberman 2003 & Horn 1995) Intrigued by these historical studies, we turned to archives to find out about photography’s use as evidence of deviance. (Appignanesi 2007; Baer 1994; Harpin 2018; Hartman 2019; Horn 2003 & Hustvedt 2011) Through re-embodying how archival images mark out meanings, we offer these images of women who were incarcerated subjects: their bodies and the annotation of their bodies’ tics, kicks and grimaces that were the site of epistemological frontiers. (Horn 1995 & 2003; Hustvedt 2011)

We turned to Charcot’s archives of the Salpêtrière asylum in Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière and to the women he captured in silent screams. We looked to the images that indicate proof of women’s thin skin—the evidence of which is marked on their bodies as male scholars would inscribe words on their bare backs and watch the welts rise. This conflation of word and flesh and the repetitious nature of the experiments hints at the volume of women subjected to these tests; for whom being photographed was to be taxonimised as hysterical—documented and stored in archives testifying to madness. Anna Harpin’s study of madness and performance works through the ways madness acts on bodies, informs representations and is inflected in narratives. The work of performance can expose how understandings of deviance are constructed through and by representations. She draws on ‘Baer’s reading of Jean Martin Charcot’s Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière [that] proposes a structural relationship between photography—particularly the use of the photographic flash—and psychoanalysis’. (Harpin 2018: 95) Harpin’s work on madness in performance offers a valuable consideration of how representations were forged not merely as objective ‘proof’ of madness, but that photography in particular staged the symptoms or signs of deviance in a violent pursuit of epistemological innovation. She goes on to show that:

The flash constitutes a connection between pathology and technology, for it was through its use that Charcot produced the very disease that he desired to cure. The hysterical catalepsy provoked by the discharge of the photographic flash ‘retains by way of the body what photography retains by way of the camera: it freezes and retains the body in an isolated position that can be viewed and theorized’ (Baer 1994: 53, cited in Harpin 2018: 95) [5]

These views reiterate that photography’s role in reproducing criminalised or deviant subjects is predicated upon the ethics of relation between social and juridical discourses; and in particular, the label ‘mad’, ‘criminal’, or ‘deviant’.[6] The significance, then, of a means of revising how visual cultures organise hierarchies and ways of seeing, could enable different applications of hegemonic value that can unsettle fixities of such labels. Thinking about the relationship between early photography and shame, Marxist photographer Allan Sekula says:

The new medium did not simply inherit and ‘democratize’ the honorific functions of bourgeois portraiture. Nor did police photography simply function repressively … Every portrait implicitly took its place within a social and moral hierarchy. The private moment of sentimental individuation, the look at the frozen gaze-of-the-loved-one, was shadowed by two other more public looks: a look up, at one’s ‘betters,’ and a look down, at one’s ‘inferiors’. (Sekula 1986: 10, emphasis in original, cited in Carrabine 2014: 138)

It is significant here to note the correlation Sekula is making with class, and the role of public performativity of hierarchies. In the present day, as Mirzoeff has demonstrated (2011; 2013; 2017), this must be understood in relation to racialised optics that reproduce violence.

What we would like to emphasise is the significance of representations of state institutions whose actions are often domesticated through regimes of invisibility. Cultural criminologist Michelle Brown asks us to conceive of the significance of photography in making the spectacle of incarceration (for crime or madness) evident in the public sphere:

Because the prison and its populations are largely invisible, because they are made to exist only in the jettisoned reaches of our society’s landscapes, the possibilities of knowing them through seeing are foreclosed and our ‘theories of images and visualities’ must address the catch-22 of the spectacle of disappearance and the human-in-a-cage as the sole modes of visibility. Out of these dilemmas, a space of political urgency for making sure that the incarcerated are visible as disappeared subjects has materialised among activists. (2014: 186)

In her book Prison Cultures: Performance, Resistance, Desire, Walsh explores how the notion of unruly women emerging from criminology is perpetuated in performance and visual cultures. (Walsh 2019) She works with Lynda Hart’s reflection on the preoccupation with the

(im)morality of women and the ever-present paranoia that women possess an inferior sense of justice’. She goes on to state that psychoanalysis ‘obsessively reproduces ‘women’ as implicitly dangerous. (1994: 25)

As explored in the book, this relates to the discursive characterisation of all women as dangerous, modelled by the early criminologist and scientific racist Cesare Lombroso (1895). Criminology does not escape from this – and tends to maintain and confirm ‘woman’ as a problematic signifier, to be grounded by means of further identification; namely by assessing and articulating how ‘good’ or ‘bad’ she is.

Lombroso’s nineteenth century anthropometric investigation into what constitutes ‘female offenders’ serves as a trope in order to assert the trouble of research on female delinquency. Lombroso constructed taxonomies of criminal bodies by learning how to read the ‘living documents’ contained in prisons as what he called ‘palimpsest[s] in reverse’. (cited in Horn 1995: 113) His claim was that if ‘read correctly’ the body-as-text ‘yielded up its submerged truths: the signs of degeneration and atavism’. (Horn 1995: 113) His methodology, underpinned by biological determinism, included pictorial representations of criminals’ characteristics as well as detailed measurements of facio-cranial dimensions. When published, his comprehensive study of female criminals was constructed against imagery of ‘normal women’, in order that the ‘female offender might become distinct, visible, and legible’. (1995: 115) Lombroso and Ferrero write: ‘the child-like defects of the semi-criminal are neutralised by piety, maternity, want of passion, sexual coldness, weakness and undeveloped intelligence’. (1895: 151) Seen together, their images of deviant women do not form a coherent story about what constitutes a female criminal, instead suggesting that all women demonstrate some of the characteristics they identify in the deviant bodies. David Horn shows that Lombroso merely pathologises women in general, remarking that ‘the normal (sic) woman … embodied potential criminality [and was] constructed as both normal in her pathology and pathological in her normality’. (1995: 121)

Un-archive: Talking back to Lombroso & Charcot

In our collaborative project that started out as a dinner party conversation, we took as a starting point archives as repositories of traces of living. Like photographs, they capture and store memories, moments and histories. They are not live but record liveness and presence; and in the present, they demand interpretation. To this end, our interpretation moves beyond seeing the images as final and complete, but as starting points for new narratives. In the spirit of Hartman’s ‘wayward women’ (2019) and generated from a prosthetic approach (Garoian 2008 & 2013), we conceived of past deviance in relation to and informed by the present. Our project is indebted to artists such as Australian artist Caroline Garcia, whose videographic works insert her dancing body into scenes of films by Western filmmakers as a redress to the ethno-hierarchical tendency for visual culture’s erasure of people of colour. (Blackmore 2018) Garcia’s approach, along with Hartman’s, focuses on the scopic field of whiteness as determining whose bodies count and whose do not. In our approach, we identify, in addition to the replication of whiteness in gender norms (for instance insisting that feminine women take up little space, are delicate, and have hair that is not unruly, and no visible body hair). In the return to archives, we considered how these assumptions intersect with ethnic ‘difference’; with poverty and class to form a category of women that would always already be defined as deviant if read according to the tropes of hegemonic whiteness.

Our focus in the ‘un-archive’ is on revisiting the contested archives of the scientists Lombroso & Charcot, whose photographic work signals a view of women that is partial, disturbing, and banal. In order to redress this, we chose to critique their documentation of deviance both as scholars and through the body. As an extension to the original sequence of deviant women, we revisited the archives of Salpêtrière and the typologies of Lombroso. We anticipated that we could dis-establish the crude depictions of deviance by adding a wider range of female bodies to the archive. By positioning ourselves as sitters in this photographic archive, we aim to bring a question of lived experience of deviance to the fore. In doing so, we cite our own bodies and beings as deviant, and unruly.

Found Text (After Charcot)

‘Behold the Madwoman—a story by Didi-Huberman’

Behold the madwoman who dances by, as she vaguely recalls something. Children chase her with stones, as if she were a blackbird. Men chase her with their gaze. She brandishes a stick, pretending to chase them, and then continues on her way. She loses a shoe on the road and doesn’t notice. Long spider legs circulate around the nape of her neck—it’s only her hair. Her face no longer looks human, [or] so it seems for an instant, and she bursts out laughing like a hyena. She lets shreds of sentences slip out, which, if stitched back together, would make sense to very few; but who would restitch them? Her dress, torn in more than one place, jerks about her bony legs covered in mud. She walks straight ahead, carried along like a poplar leaf, with her youth, illusions, and past felicity, which she sees again through the whirlwind of her unconscious faculties. Her step is ignoble and her breath smells of brandy. Why does one still find oneself thinking she is beautiful?

The madwoman makes no reproaches; she is too proud to complain and will die without having revealed her secret to those who take interest in her, but whom she has forbidden to address her, ever. Still she calls to them with her extravagant poses. Children chase her with stones, as if she were a blackbird. Men chase her with their gaze. (Didi-Huberman 2003: 67)

Stigma: A letter to Lombroso’s Women

When in performance for camera, we imagine our bodies into the experience of your bodies, we find a yawn of time has separated us from the bitter wound of your raised letters that signal bodies written on by doctors, psychiatrists, medical men.

Stigma stings, pierces, makes holes, separates with pinched marks and in the same movement distinguishes—re-marks—inscribes, writes. (Cixous 2005: xi)

When posing for the photograph I can look into the shutter

I am

more than an outlaw

I am the spectator and the spectacle.

Stigma wounds and spurs, stimulates. (Cixous 2005: xi)

When I surface my own shame on my body, I curate how you see it by framing where your gaze is directed. Charcot’s women of Salpêtrière didn’t get that choice.

Stigma always kills two birds with one stone. (Cixous 2005: xi)

This text, seen alongside Fenia’s series, foregrounds how photographic practice can deliberately consider its historical antecedents; the documentation of deviant women. In her playful series that gestures towards fairytale tropes, her girl/women/monstrous figures insist on being a spectacle. In particular, her deliberate focus on hair and her refusal to perform gender norms sets the series as a provocation on deviance. This prompts a return to Sara Ahmed’s invocation of the wilful child the fairytale of the girl’s arm that refuses to remain buried, or the dancing girl with the red shoes whose actions disrupt norms of everyday life, whose refusal to comply, or to be docile, or to perform to conventions can have extreme consequences. (2014 & 2017) By adopting this performative mode of refusal to be archived, we consider the images produced by Fenia a playful, and perhaps risky attempt to render gender prosthetic or ventriloquist.

The shift to engaging with the archives moved our understanding beyond tropes of deviance that we might adopt as characters (the sleek party girl, the ballerina, or red riding hood). In the process of considering the archival images, Lombroso and Charcot enraged and enthralled us in their systematic collection of troubled, vulnerable, marginalised women under categories of ‘deviance’. Fenia’s re-performance adopts some of the well-known tactics of feminist performance: citation, a focus on the abject, and ambiguous relationships with the autobiographical. Yet in taking the place of women in madness, in confinement the work is less about affirming these tropes than posing the question with the body. The work undermines the shoddy science that seeks to measure, to taxonomise, to make legible the lived female experience.

Photography then and now correlates with what Sianne Ngai calls the epistemological imperative of ‘interesting’ as an aesthetic category: that is, a zooming in and out between what is general and what is particular. What is general (hysterical women) and what is particular (this hysterical woman). What is general (female) and what is particular (this hairy female). It asks of viewers to position themselves in relation to the subject, always inferring the norms of bodies and their deviant Others.

What might it mean for visual cultures if gender refuses to perform—or at least, if, as in the examples from across these disciplinary borders, norms are radically called into question when gender exceeds itself, and when bodies refuse to be disciplined? Through the course of working alongside the archival images, we heed a call from Ferrell and van de Voorde to conceive of the ‘iconoclasm’ of cultural criminology, and in particular the use of the visual, saying: ‘we might best learn the promise of documentary photography if we embrace it as an adventure in unlearning’. (Ferrell & van de Voorde 2010: 48)

The visual performance essay has sought to upend the sensibility of types/ tropes/ symptoms or scales that contribute towards pathologising poverty, ‘othering’ ethnic minorities or foregrounding difference from a restricted set of norms. With a concentration on gendered deviance and its specific inflections in feminist visual criminological understandings, we hope to contribute to developing awareness off photographic modelling that can use the ingrained expectations, standards or forms to undermine or destabilise assumptions about being, womanhood or belonging.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Daz Disley, our artistic collaborator.

Some of this material was first presented by Walsh in an invited talk: ‘Written on the body: The problem of evidence and gender’s performance’ at the University of Rostock’s cross disciplinary research group on gender and sexuality at the invitation of Andrea Zittlau (Autumn 2016). It was developed into a practice-research visual essay in collaboration with Fenia Kotsopoulou in ‘The Lived Female Body in Performance’ symposium organised by the Bodies Research Group at the University of Leeds School of Performance and Cultural Industries (April 2019).

Notes

[1] She continues: ‘So pervasive was Charcot’s work and so profound its impact on the popular imagination that it rapidly influenced the performance style of the Parisian cabaret and vaudeville ‘with a new repertoire of movements, grimaces, tics and gestures’, which mimicked the comportment and disposition of the Salpêtrière patients’. (Bourke 2014: 164, cited in Harpin 2018: 95)

[2] For more on visual criminology see Michelle Brown (2009 & 2014) and Henne & Shah (2016).

[3] This view comes from thinking with visual culture and art education theorists Charles Garoian and Yvonne Gaudelius (2008). Their book Spectacle Pedagogy is what has offered the framework for thinking about the work of images and how they contribute to, define and create visual cultures. In turn, much of this ground was mined by Susan Sontag in the work On Photography (1973).

[4] Garoian maintains awareness of not simply adopting ‘prosthesis’ as a trope outside of consideration of disability studies. He cites Sarah S. Jain (1999), who ‘warns against limiting the use of the prosthetic trope merely to argue in favor of or in opposition to technology when ‘the wounding ingredients of technological production [those academic, institutional and corporate proselytizing offenses to the body committed through schooling, labor, and consumption] remain continually under ontological erasure’. (cited in Garoian 2008: 223)

[5] We heed Ahmed’s warning not to fall into the trappings of the body’s ontological status she sees in much feminist theory (2000).

[6] Our thinking circulates on women’s deviance here, but we acknowledge the significant work on disability (Puar 2017); gender and sexuality (Cvetkovich 2003; Daring et al. 2012; Hart 1994 & Mohanty 2006) and the relationship between deviance and state surveillance.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (1999), ‘Phantasies of Becoming (The Other), European Journal of Cultural Studies, No. 2, Vol. 1, pp. 47-63.

Ahmed, Sara (2000), Embodying Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Postcoloniality, London: Routledge.

Ahmed, Sara (2004), The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ahmed, Sara (2014), Wilful Subjects, Durham: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, Sara (2017), Living a Feminist Life, Durham: Duke University Press.

Appignanesi, Lisa (2007), Mad, Bad & Sad: A History of Women and the Mind Doctors 1800 to the Present, Toronto: MacArthur and Co.

Baer, Ulrich (1994), ‘Photography and Hysteria: Towards a Poetics of the Flash’, Yale Journal of Criticism, No. 7, pp. 41-78.

Blackmore, Kate (2018), ‘Video Becomes Us: Caroline Garcia. Staple Fiction’, http://staplefiction.com/video-becomes-us-abc-television (last accessed 29 June 2000).

Bourke, Joanna (2014), The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, Michelle (2009), The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society, and Spectacle, New York: New York University Press.

Brown, Michelle (2014), ‘Visual Criminology and Carceral Studies’, Theoretical Criminology, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 176-197.

Carrabine, Eamonn (2010), ‘Visual Criminology: History, Theory and Method, in Hayward, Keith & Mike Presdee (eds), Framing Crime: Cultural Criminology and the Image, pp. 103-121.

Carrabine, Eamonn (2014), ‘Seeing Things: Violence, Voyeurism and the Camera’, Theoretical Criminology, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 134-158.

Cixous, Helene (2005), Stigmata, translated by Eric Prenowitz, London: Routledge.

Crimp, Douglas (2005), ‘Portraits of People with AIDS’, in Mariam Fraser & Monica Greco (eds), The Body: A Reader, London: Routledge, pp. 204-207.

Cvetkovich, Ann (2003), An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, Durham: Duke University Press.

Daring, C.B., J.Rogue, Deric Shannon, & Abbey Volcano (eds) (2012), Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Understanding Power & Desire, Oakland: AK Press.

Didi-Huberman, Georges (2003), Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Oconography of the Salpetrière, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Eng, David & David Kazanjian (eds) (2003), Loss: The Politics of Mourning, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Faith, Karlene (2011), Unruly Women: The Politics of Confinement and Resistance, 2nd edition, New York: Seven Stories Press.

Ferrell, Jeff & Cécile van de Voorde (2010), ‘The Decisive Moment: Documentary Photography and Cultural Criminology, in Keith Hayward & Mike Presdee (eds), Framing Crime: Cultural Criminology and the Image, New York: Routledge, pp. 36-52.

Garoian, Charles R. (2008), ‘Verge of Collapse: The Pros/thesis of Art Research’, Studies in Art Education, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 218-234.

Garoian, Charles R. (2013), The Prosthetic Pedagogy of Art: Embodied Research and Practice, Albany: State University of New York Press.

Garoian, Charles R., & Yvonne Gaudelius (2008), Spectacle Pedagogy: Art, Politics, and Visual Culture, New York: State University of New York Press.

Harpin, Anna (2018), Madness, Art and Society: Beyond Illness, London: Routledge.

Hart, Lynda (1994), Fatal Women: Lesbian Sexuality and the Mark of Aggression, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hartman, Saidiya (2019), Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Henne, Kathryn & Rita Shah (2016), ‘Feminist Criminology and the Visual’, Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Criminology, DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.56 (last accessed 29 June 2020).

Horn, David G. (1995), ’This Norm which is not One’: Reading the Female Body in Lombroso’s Anthropology’, in Jacqueline Terry & Jennifer Urla (eds), Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.109-128.

Horn, David G. (2003), The Criminal Body: Lombroso and the Anatomy of Difference, London: Routledge.

Hustvedt, Asti (2011), Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-century Paris, London: Bloomsbury.

Jain, Sarah S. (1999), ‘The Prosthetic Imagination: Enabling and Disabling the Prosthesis Trope’, Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 31-54.

Lombroso, Cesare & William Ferrero (1895), La donna delinquente (The female Offender), London: T. Fisher Unwin.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas (2011), ‘The Right to Look’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 473-496.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas (ed.) (2013), The Visual Culture Reader, 3rd edition, London: Routledge.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas (2016), How to See the World: An Introduction to Images: From Self-portraits to Selfies, Maps to Movies, and More, New York: Basic Books.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas (2017), The Appearance of Black Lives Matter, Miami: Name Publications.

Mohanty, Chandra M. (2006), ‘US Empire and the Project of Women’s Studies: Stories of Citizenship, Complicity and Dissent’, Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, Vol. 13, No. 1,: pp. 7-20.

Ngai, Sianne (2012), Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nguyen, Mimi T. (2015), “The Hoodie as Sign, Screen, Expectation and Force’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, No. 40, Vol. 4, pp. 791-816.

Puar, Jasbir (2017), The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability, Durham: Duke University Press.

Sekula, Allan (1984), Photography against the Grain: Essays and Photoworks, 1973-1983, Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

Sekula, Allan (1986), ‘The Body and the Archive’, October, No. 39, pp. 3-65.

Sedgwick, Eve K. (2003), Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham: Duke University Press.

Sontag, Susan (1973), On Photographym New York: Penguin Books.

Walsh, Aylwyn (2019), Prison Cultures: Performance, Resistance, Desire, Bristol: Intellect.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey