Comics, Feminism, and the Future: Feminist Figuration in Parable of the Sower & Shuri

by: Rebecca Scherr , March 30, 2023

by: Rebecca Scherr , March 30, 2023

Who are my kin in this odd world of promising monsters, vampires, surrogates, living tools and aliens? … Who are my familiars, my siblings, and what kind of livable world are we trying to build? (Haraway 1997)

Science fact and speculative fabulation need each other, and both need speculative feminism. (Haraway 2016)

***

I’ve been thinking about the future a lot these days—not my own personal future, but the future of the planet, of humanity and habitat, of species and environments—and wondering where we are going. Many of us are doing the same, for the same reasons: political and environmental struggles and the complex ways these intertwine with each other. This is fuelled by the knowledge that a tipping point of destruction has long been passed and our world is in free-fall, and we are flailing around amidst competing ways of engaging (and perhaps mostly not engaging) with this free-fall. In my attempts at thinking about the future, I have been struck again and again by how difficult it is to actively think futuristically. Western forms of knowledge have created whole fields and methodologies for studying the collective past but there has been little investment in how to think about the collective future. This essay is an attempt at finding some pathways and trying out some ideas towards thinking futuristically. I use literary, comics, and feminist studies to begin to sketch the possible contributions of comics and graphic narratives towards disseminating future-oriented visions of justice as it manifests in bodily life.

The concept and practice of time is as central to the medium of comics as pen and ink; it is part of what comics form is made of and how readers experience comics. Much has been written about comics and temporality: the comics page as a kind of temporal map (Chute 2008: 455); comics as a medium whose very form reveals its own engagements with narrative temporality (Menga & Davies 2020: 670); and as a medium where the perception of time and space are inseparable (McCloud 1993: 100). In short, time in comics encompasses the visual aesthetic and the abstract perceptual elements of the art form. Many comics scholars who study time in comics focus on how various artists use the space of the page to represent private and public histories, how comics form allows for the layering of past and present in inventive and instructive ways. These kinds of temporal experiments are especially central to the power of non-fictional, canonical graphic works like Maus, Persepolis, and Fun Home, works that find new ways of representing history and trauma through the flexible temporal and spatial possibilities that graphic narratives offer.

Yet a discussion about how we as comics scholars can think about what time in comics offers in terms of future-visualising and future-thinking, and why this might matter, has only recently begun (Ursini et al 2017 and King and Page 2017). This is despite the fact that future speculative works and comics that engage with transhumanism and posthumanist ideas have been a part of comics art (and in several national contexts) for many decades (King and Page 2017: 1-2). There is, to put it mildly, no shortage of future-speculative works, from the post-apocalyptic and dystopic to techno-saturated and posthuman worlds. Contemporary future-dystopic comics like Snowpiercer and Sweet Tooth have recently been made into television series, and several screen adaptations featuring the work of Octavia Butler and Nnedi Okorafor—the two writers I focus on in this essay—are currently in various stages of development. This points to the other reason I find it strange that there has not been more work done on futurism and comics. Future speculative narratives in general are currently a central concern within popular culture, their recent surge in popularity a result of the anxieties of climate catastrophe and pandemic. Futurism more generally has very recently become a buzzword and a widely studied topic across a vast array of humanistic disciplines.

Fiction has a powerful part to play in this current grappling with the future, as so much of how we engage with the future is through imaginative narrative—in other words, through how we tell stories and who or what gets to tell stories about the future (Ghosh 2021). Speculative fictions—and especially speculative comics with their highly experimental relationship to time—remind us that time itself is more akin to a story than a scientific fact. Through stories, we are reminded that time is not ‘one thing’ for all, but has been experienced, discussed, interpreted, and reinterpreted differently throughout history and across cultures, and that time stories can therefore be seen and experienced differently in the future. In fact, the modern idea of time as ‘one thing’ is (and has been) an extremely effective tool of power, and the history of this idea speaks of immeasurable violence and suffering. Just think about the forcible imposition of time stories that control labor; ones that force a particular story about the origins of the world and of humanity; colonialism and empire are tightly bound up with the violence of time-stories; and ideas about what constitute ‘proper’ lifetimes are part of what shape the parameters of normativity and outsider-ness. Fiction has been a place that, while mostly confirming and strengthening the time stories of hegemonic power, has also been an active place for contesting such stories, and for opening pathways to alternative time stories, very often in the guise of speculative fictions.

Yet. As a long-time reader of speculative fiction in its visual and textual forms, I am still amazed at how often a speculative writer who has incredible powers of imagination simply cannot conceive of a future time where normative conceptions of gender and sexuality have shifted in any meaningful way. Examples are pretty much endless. This, of course, has started to change somewhat, especially with the ever-increasing diversity of speculative writers, and thanks to pioneers like Samuel Delaney and Ursula Le Guin. Yet, there are still far too many works where an author cannot imagine a future reconceptualisation of how identities are created and experienced. Far too often there is an attempt at, say, introducing queer characters or overtly feminist characters in a speculative work, but no real attempt at interrogating the perspectives and power structures that maintain normative ideas about bodies and identities. Whole new worlds can be elaborately constructed, but present assumptions about gender, sexuality and identity more generally so often remain more or less the same. For this reason, I am interested in narrowing down the enormity of speculative futurism to discuss comics and the future from a feminist perspective.

With all of the various strands I have so far brought up as keywords—the future, comics, speculative fiction, identity, feminism—my guiding questions for this essay are as follows: How do feminist comics tell stories about time? What kinds of stories do (some) feminist comics tell about the future? And my particular interest in this question is about representations of knowledge itself: what kinds of knowledge systems do comics creators engage with in speculating about feminist futures? And why might this matter?

Feminism as a movement and as theory is at its very heart a speculative project. The project of feminism is to imagine and create new worlds (Haraway 1985 and Braidotti 2022). Feminism’s ‘reconfiguration of the [human] subject’ is by default future oriented (Grosz 2002: 13). Feminist worlding in real life and in fiction reimagines power regimes, reformulates bodily signification, creates new and alternative figurations of future subjectivity and collectivity. In my opinion, posthuman feminism’s interest in reconfiguring the human subject by decentring it is one of the most important feminist projects of our moment. This is because the work of decentring requires the formulation and the retrieval of alternative systems of knowledge: the building of new ways of thinking, as well as drawing on long existing forms of indigenous knowledges that have been built on a de-centred, multispecies foundation (Bird Rose 2012). These (new/old) forms of knowledge take the ethics of relationality and multispecies life seriously. Critical posthumanism has long shown that humanism as a knowledge-system has failed to embrace the ethics of the interdependence of all life; and because humanism is strongly rooted in patriarchal and capitalist-colonialist paradigms, it has failed to deliver real liberation despite its stated intentions. Humanism as a mind-set is in fact a deep denial of the shape of interdependent reality, contributing greatly to the catastrophes that we see all around us.

As Donna Haraway wrote nearly 40 years ago in her iconic ‘Cyborg Manifesto,’ speculative fiction is one of the areas where posthuman feminist theory often meets popular culture and is therefore a powerful vehicle for thinking about feminist futures and their visual and textual manifestations. It is a creative space where writers and artists use the plane of the page (virtual and material) to envision, question, experiment, stretch the imagination and begin to sketch what a feminist future could look like and feel like. Haraway clearly saw the power of such writing and visualising to articulate new ways of being. As Sami Schalk has most recently put it, reading and writing feminist speculative fiction can ‘[change] the rules of reality’ and change ‘how we read and interpret’ categories of identity and therefore the nature of discourse and rights (2018: 11).

Comics has been and can become an even greater medium of popular narrative where such speculative fictions play a role in shaping discussions around feminism and the future. Filipo Menga and Dominic Davies argue that comics worlds have strong tendencies towards being ‘critically posthumanist’ in that they ‘interrogate’ the potentials and limitations of knowledge-systems through narrative structure and compositional strategies (2020: 665). They argue that because of comics’ grid structure and multimodality, time stories in comics allow for ‘a more complex engagement with narrative time’ because ‘[t]ime is held spatially on the page(s) of the comic, inviting readers to think beyond the linear confines of conventional filmic or novelistic forms’ (2020: 670-1). I find their argument intriguing, especially for thinking about the structure of narrativity (‘the grid’ in comics) and how it can rework perceptions of past, present, and future. What I want to explore in this essay, however, is a different aspect of the comics form that I consider to be ‘critically posthumanist’ (i.e., a critique of humanism) and that I believe is especially productive for analysing comics that foreground identity and identity formation as a major part of, and intervention into, the discourses of the Anthropocene. This is comics creators’ engagement with what feminist theorists Haraway and Rosi Braidotti call feminist ‘figuration.’

***

There is probably no more paradigmatic example of feminist speculative fiction and engagement with alternative systems of knowledge than science fiction writer Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower. Beloved during her lifetime, Butler has garnered even more posthumous fame in recent years, and is widely considered the ‘grandmother’ of contemporary versions of Afrofuturism, posthuman literature and feminist futures. It is Sower that many feminist critics turn to when writing about representations of feminist future thinking (Braidotti 2020, Haraway 2016, Schalk 2018). In this essay, I will analyse the 2020 graphic novel adaptation of Sower by Damian Duffy and John Jennings, an adaptation that sticks quite closely to the original novel. While the novel certainly presents ample opportunities for examining feminist figuration, it is in the comics medium with its intense colours and movements, I will argue, that Sower’s figuration takes on a particularly visceral form.

Parable is set in the near future (the mid to late 2020s), and tells the story of Lauren Olamina, a teenager living with her family in a dystopic Los Angeles where climate change has led to infrastructure meltdown and a society in the throes of total collapse. Lauren, who has a condition called ‘hyper-empathy’ and an unusual clear-sightedness about the direction of society’s collapse, is forced by fatal circumstances to leave her family’s home, and survive on the open road with a group of other survivors, all the while working on a manuscript outlining her ‘new’ religion, which she calls Earthseed. Earthseed is loosely based on a sort of Buddhist philosophy and is summarised in the novel’s opening text: ‘All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you. / The only lasting truth / Is Change. / God / Is Change’ (Butler 1993: 3).

This brief synopsis exemplifies the apparent contradiction that is often at the centre of feminist speculative fictions. This is the narrative’s attempt to reconcile two very different and often seemingly oppositional future paths. The first path envisions new structures and ways of thinking and seeing that work to realise egalitarianism and social justice, highly valuing forms of knowledge that allow for these perceptual and philosophical changes to flourish. In Sower, this manifests as Earthseed and Lauren’s small but growing following as a spiritual leader; and through the character of Lauren herself, who is a black, female, disabled heroine and leader. Earthseed is a spiritual vision that also hints at de-centring the human; as Lauren writes later in reference to the ‘God is Change’ verse, ‘Consider: whether you’re human, insect, microbe, or stone, this verse is true’ (Duffy and Jennings 2020: 60). ‘God’ in Sower is not pictured in relation to humans or humans as pale reflections of God, but rather God refers to the impermanence of time itself and encompasses all forms of life. The second path that intersects with this is deeply pessimistic and recognises the current geological era of the Anthropocene as a time of mass extinction (Kolbert 2014). This is represented in Sower by the text’s setting of a dystopic California burnt, parched and in ruins; and the USA as entirely overrun with violence, exploitation, death, and dehumanisation. In short, in a great number of feminist future visions like Sower’s, utopian impulses meet climate disasters in their multiple possible manifestations. Haraway describes Butler’s engagement with these paths as a concern with what she calls ‘wounded flourishing’ (2016: 120). I find ‘wounded flourishing’ to be an apt phrase to describe these duelling yet intertwined impulses in much feminist speculative fiction. It is also a phrase that is key to analysing the ways in which feminist figuration takes shape in Sower.

Comics form excels at representing contradiction by its ability to visually display the connections embedded in (seeming) contradictions, and as such, I argue, is one of the most direct and useful vehicles for visually and verbally representing this concern with “wounded flourishing.” This is partly due to comics ‘biocularity,’ which Marianne Hirsch explains is the medium’s ability to eradicate the apparent boundaries between texts and images: ‘[w]ith words always already functioning as images and images asking to be read as much as seen, comics are biocular texts par excellence. Asking us to read back and forth between images and words, comics reveal the visuality and thus the materiality of words and the discursivity and narrativity of images’ (2004: 1213). As a result of this continual slippage, comics has the unique ability to ‘hold’ seeming contradictions in the flash of a frame, in a single image and/or word, in short sequential passages, and in doing so, ‘words and images that in their media representation and repetition threaten to lose their wounding power reappear in newly alienated, and thus freshly powerful, form’ (Hirsch 2020: 1215). Note how Hirsch, too, uses the word ‘wounding’ to describe a productive act in the realm of trauma and representation; and her claim is that comics are a particularly useful medium for enacting this productive wounding. This is why I think that Sower works so well in graphic narrative format: ideas about climate catastrophe and future worlding leap off the page in ways that are made visceral, new and strange. ‘Wounding’ in Sower is thematic, as I have been pointing out, and it functions as a kind of graphic readerly address. As such, it is a vehicle for opening layers of inquiry, critique, and knowledge.

Wounding is central to understanding Lauren’s function in Sower. Her condition of hyper-empathy is something she was born with as a result of her mother’s drug addiction while pregnant; her own story of wounding began before she was even born. With hyper-empathy, Lauren literally feels others’ pain in and on her body, experiencing the same pain and wounding she witnesses with her eyes. Even the sight of another’s blood could cause Lauren herself to bleed. She is physically unable to draw a line between her own and others’ wounds, and in the violent and decaying world of Sower, the pain of others is something that Lauren must ceaselessly adapt to and navigate. How Lauren’s literal figure becomes a figuration in the text speaks to the implications of this wounding as a source of knowledge, complexity, and identity.

The feminist concept of figuration (Haraway 1997) can take on an almost literal manifestation in comics art and is deeply related to comics’ biocularity. Figurations are ‘verbal or visual’ representations which contain, in the words of Haraway, ‘contestable worlds’ that ‘map universes of knowledge, practice and power’ (1997: 11). Haraway uses the image of a seed or a microchip to explain the concept of figuration: figurations are ‘dense nodes that explode into entire worlds of practice’ and these practices, moreover, displace and ‘trouble identifications and certainties’ (1997: 11). Haraway’s famous figurations include the cyborg and, most recently, companion species—two figures that drive her post-humanist theoretical work. Figurations allow us to explore the often contradictory political, ethical, material, technological and bodily dimensions of embodiment and being within our technoscientific world. Thus, like biocularity, reading for figurations is a method for examining the ways that contradictions can be represented as connective, uncanny and productive. In this way, they can also act as vehicles towards re-thinking habitual ideas about identity and power. Figuration, in tandem with biocularity in comics, allows for conflicting concepts to interact on the page, and through these figurations, readers may shift their ideas and make decisions differently (see Bastian 2006: 1029-30).

Charlotte Johanne Fabricius is the first comics scholar to apply feminist figuration to comics specifically, and she does so in her recent PhD thesis on Super-girls. In fact, Fabricius uses figuration specifically to comment on ‘the Supergirl’ as a popular culture figure that signifies futurity in her many embodiments. Fabricius reads the figuration of the Super-girl as a site for the mapping of contested identities, power relations, and the possible future of girlhood itself (2020: 211). While I do not have a new, specific figuration (like the Super-girl or the Cyborg) that I name and explore in this essay, previously theorised figurations like ‘companion species’ play a role in my close reading. My main interest, instead, is much more general: it is to explore the political potential of comics as a source for reading literal figures—that is, ‘the figure’ in an art-compositional sense—as figurations. My claim is that many feminist comics creators use figuration to tell stories about feminist futures. Following this, I am advocating for using figuration as a kind of reading and interpretative practice in comics studies, a ‘way of seeing’ that allows for something as large, abstract, and contradictory as ‘knowledge systems’ to be made visible on the comics page, and for these interpretations to contribute to serious political and social discourse.

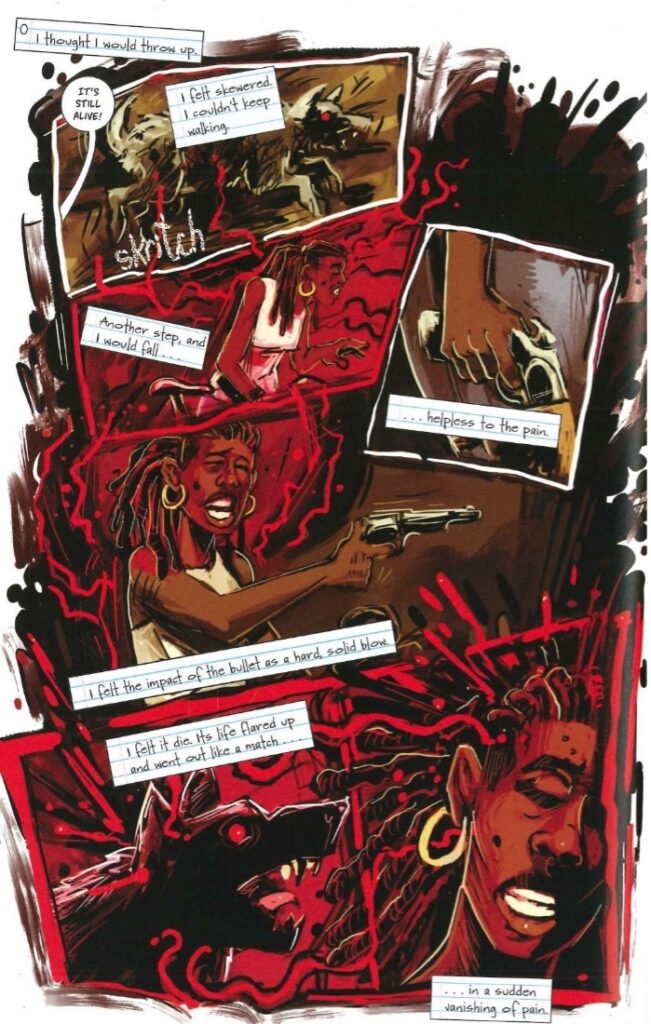

Both in the novel and in the graphic narrative, Lauren’s hyper-empathy as a source of wounded knowledge is explored in an early scene where Lauren, along with several members of her community, leave their gated neighbourhood and ride their bicycles to a nearby canyon for target practice. There they encounter wild dogs, and this encounter is key to understanding the ways in which Sower figures and reconfigures the knotty strands of self and other, time and space, human and non-human animal, a broken world, cruelty, compassion, and survival. Here readers find out that in Lauren’s world, dogs are no longer the companion species they once were. That form of human and non-human kinship is impossible in the climate-disaster future of Sower: ‘The dogs—or their ancestors—used to belong to people … but dogs eat meat … only rich people keep guard dogs,’ Lauren explains (Duffy and Jennings 2020: 30). Dogs and humans are in competition with each other; there is no room for companionship between species in the world of Sower. Yet at the very same time, the narrative establishes a strange, hidden kinship via Lauren’s hyper-empathic body and a wild dog’s death. Lauren encounters a dog who has been shot by a member of her group but is still alive and crying out in pain. Lauren feels the dog’s suffering in her body: ‘I felt skewered. I couldn’t keep walking … Another step and I would fall … helpless to the pain’ (Duffy and Jennings 2020: 34). Despite this, she manages to pull out her gun and shoot the dog to end its suffering, having no idea how this action will affect her, afraid she too might die like the dog. ‘I had felt its pain, like a human,” Lauren writes, ‘I felt its life flare and then go out … and I was still alive’ (Duffy and Jennings 2020: 35).

There are numerous strands of entanglement in this intense moment, both visually and textually. The use of dogs, one of our world’s most cherished companion species, is here used to illustrate the consequences of global warming by making strange the habitual kinship relations between humans and dogs. The link between Lauren and the dog is intricate, and encompasses connectivity and disconnection simultaneously; she is both afraid of the dog, and her hyper-empathy renders her deeply compassionate towards it. She also, in a sense, embodies the dog in the moment of its wounding and death. In the graphic form, this scene functions as a highly effective figuration: a fast, compact, and compressed route towards displaying quite complex arguments about bodies, the world, and knowledge. The kinds of questions that lurk in this moment speak to necessary inquiries about the future of ourselves and the planet: What is our relationship to, and what kinds of obligations do we have, towards non-human animals in these times of crisis? How might the change in the status of ‘the dog’ in a possible future signify a change in status of ‘the human?’ What are the ties that bind us to other life forms, not only in terms of survival, but in terms of identity? Who we are as a species? What are the boundaries that can’t be crossed? How might our thinking change if we all felt the pain not only of other humans but of other species? These are only a few of the enormous questions embedded in this figurative moment almost like a seed: these profound questions are encapsulated in a short, sharp series of images and narrative. They explode into relevance when the reader’s eyes ‘touch’ the figures.

In the moment Lauren experiences the dog’s pain and then its death by her own hand, normative ideas of time and space collapse, gesturing towards a kind of painful connectivity that challenges notions of a discrete bodily self and other in space and time. In the graphic version, the death of the dog is also a moment where the literal representation of wounding—Lauren’s and the dog’s—works, in an aesthetic sense, to ‘wound’ or ‘touch’ the reader. Duffy and Jennings’ use of line and colour evoke a visceral response that employs haptic visuality (Scherr 2013), that is, their visual style allows the reader to register a kind of felt knowledge, a cognitive echo of Lauren’s bodily sensation of the dog. The entire graphic novel uses a colour palette that I would call a palette of the Anthropocene. Shades of brown speak of dust and drought; burnt reds and oranges speak of heat and fires; blues and blacks of the shades of days and nights without electric light. The dog’s death scene stands out as stylistically unique within this palette. The panel frames are much shakier than in the rest of the work and crossed by blood-red lines that signify physicality, connectivity, and pain. The pen lines are quite electric in their visual design and effect and heighten the already present sense of danger the graphic novel has already established [Image 1]. In the moment of the dog’s death, the drawing makes it visually unclear who is dying: Lauren or the dog, or both, as both beings are surrounded by the electrifying red ribbons of blood and pain. And yet, there is a vertical red line functioning as a gutter that separates the dog from Lauren: it is a visual representation that depicts the simultaneous connection and disconnection between Lauren and dog, human and non-human animal. In that gutter the reader is pulled into the comics world (McCloud 1993: 65-66), made to imagine and interpret this confusion and uncanniness. In that moment of reading across the blood-red gutter that both connects and separates human and dog, questions about the ethics of multi-species life flash off the page, touch the reader, and become a site for philosophical questioning regarding identity and ethics. This exemplifies the power of reading figures in comics as (feminist) figurations.

Figurations are multi-faceted and comment on, reflect, and refract several aspects of a given set of concerns. Looking at the representation of Lauren’s hyper-empathic body from a slightly different yet related angle, her role in the text is not only about troubling the lines between difference and sameness when it comes to humans and other species, but it also troubles commonplace bodily discourses about ability and disability, and how these states of being might signify in the future. Schalk, in her highly influential reading of Sower, positions Lauren’s condition of hyper-empathy not as an illness but rather as a type of disability, and further argues that in doing so, Butler’s speculative futurism offers an alternative to the often casually racist, sexist and ableist tropes rife in all kinds of futuristic speculative fiction, including in much feminist futurism (Schalk 2018). In many speculative worlds, Schalk points out, forms of oppression are ‘resolved’ by eliminating them: ‘[d]iscrimination and oppression based on difference is resolved … in many speculative fictional futures through the erasure of difference altogether’ (2018: 123). In discussing Sower specifically, she writes, ‘[u]nlike representations of a disability-free future which understand disability as incompatible with a desirable or liveable future, the Parable books represent a black disabled future heroine and theorise alternative possibilities of bodyminds’ (2018: 124-5). Schalk is referring to a common trope in much speculative fiction, and she points to one of the classics of feminist sci-fi, Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, as a paradigmatic example of this erasure of difference: in many future narratives, such as Piercy’s novel, disability is ‘solved’ by technology—thus disabled bodies do not exist in the future, and this is framed in such narratives as societal advancement.

What such a trope actually does, Schalk points out, is to fetishise the ‘unmarked body,’ the body type to which all must assimilate (2018: 123). The image of the ‘unmarked body’ is, as critical race scholars and feminist theorists have long pointed out, central in the maintenance of whiteness and power. That is, in the history of Western representation and everyday discourse, the male, white, ableist body has functioned as the unmarked, the neutral standard to which all other bodies are marked in language and visual culture by varying degrees of difference to this default. Such representations of the utopic ‘unmarked body’ of the future are not an advancement in thinking or knowledge, in other words, but instead engage with the same kinds of humanist perspectives and power structures that have ‘the perfect body’ as its central referent. The figure of Lauren’s black and disabled body works to find a way out of the quagmire of repetition, especially the more hidden ways this repetition of destructive power dynamics manifests in much speculative thinking: that is, in the fantasy of dissolving difference.

In Parable, Lauren thus functions as a figuration for an embodied future that encompasses change and radical difference. Representations of her hyper-empathic body serve as a connective link between thinking multispecies lives and thinking multi-human possibilities. This kind of embodied future is framed as a deeply ethical project, where knowledge consists of tracing and encountering radical differences and connections in multispecies life, and furthermore that this is connected to expanding categories as to who ‘counts as human’ (Butler 2004: 20), who can and must be included in the human circle of the future.

***

I turn next to a writer who has been deeply influenced by Octavia Butler’s profound meditations on feminism and the future, and who writes both novels and for comics. Nnedi Okorafor is one of the most well-known contemporary authors whose narratives consistently grapple with the ethics of multispecies life, not only as she imagines life on Earth, but also in other worlds and in outer space. Her novels and comics are feminist, African-futurist, speculative explorations of how we might re-think the idea of ‘the human’ when we attribute sentience to trees, insects, mud, mushrooms, birds, microbes, aliens, and more. Comics of course has long been a rich medium for thinking about other kinds of life forms, hybrid beings, aliens and the like, sometimes in serious and sometimes in playful ways. Okorafor manages to do both simultaneously. In Okorafor’s worlds, alien plants can talk and have transformative friendships with humans (LaGuardia 2019). Mud has profound spiritual qualities (Binti 2015). Giant space grasshoppers seek solace in music (Shuri 2020). These are just a very few of Okorafor’s imaginative engagements with speculative lives. Playfully and often humorously working with the implications of these multispecies interactions within her comics authorship, Okorafor’s writing uses imaginative world-building to ask what it might mean to attribute agency to other life forms, and how this attribution of agency might rework and revolutionise how we perceive the future and identity.

Okorafor wrote 7 issues featuring the Black Panther character Shuri for Marvel’s Wakanda Forever series, and in 2020 the issues were collected, along with 3 issues written by Vita Ayala, into the eponymously titled Shuri. Shuri is a figure who is, within the world of Wakanda, the literal embodiment of past and future, as she has access to the realm of her eternal ancestors (‘the Djalia’) as well as being the creator of the most advanced technology that is bringing Wakanda—and eventually, during the 10-issue arc, the rest of Africa—into the future. The ancestors, in fact, have a name for Shuri. They call her ‘Ancient Future.’ She quite literally figures as an embodiment of the span of time itself. The visual figure of Lauren in Sower functions as a kind of figuration of the future in which her connection to woundedness (wounded bodies, wounded world) speaks to the productive power of undoing physical and conceptual boundaries between humans and other species, and within this figuration, time itself in its most fundamental form is change, change that is painful, open, and radically encompassing of difference. In Okorafor and Ayala’s Black Panther comics, Shuri is also a figure whose image and narrative arc works as a figuration for future time, and in their experiments with time stories, Shuri as a figure embodies an ethos in which the flow of time in its fundamental form is responsibility.

In Shuri, multispecies moments abound and take place at a quick pace: Shuri inhabits the tree-creature Groot’s body for a period time; much of the story takes place at the foot of the magical Bilbao tree that is the center of Wakandan history, identity, and survival; she battles a rampaging giant space grass hopper, eventually taming it through connection and compassion; Shuri’s powers both spiritually and technologically manifest as a flock of crows; and of course, ‘the Black Panther’—a role that Shuri inhabits briefly in the series—is the name and symbol for the entire exceptionality and power of Wakanda in the Marvel universe. All this entanglement between Shuri and other life forms is always framed in ways, I would argue, that highlight time as an ethical form of responsibility. In this way, Okorafor works to invest her creative works with what Amitav Ghosh calls ‘the politics of vitality’ (2021: Loc 3602), which is both a political and, perhaps more pressingly, a narrative act:

This is the great burden that now rests upon writers, artists, filmmakers, and everyone else who is involved in the telling of stories: to us falls the task of imaginatively restoring agency and voice to nonhumans. As with all the most important artistic endeavours in human history, this is a task that is at once aesthetic and political—and because of the magnitude of the crisis that besets the planet, it is now freighted with the most pressing moral urgency (Ghosh 2021: Loc 3292).

Such narrative acts work to reformulate the relationship between humans and non-human others as reciprocal, and thus undoes many of the conceptual boundaries upon which humanism’s principle of domination relies.

In the very first issue of Shuri, her character introduces herself to the reader as she effortlessly shape-shifts and blurs distinctions between advanced technology and nature; between animal, human, and supernatural lives; and between past, present, and future. [Image 2] In a sequence where Shuri practices the use of wings she created in her lab, the frames begin by picturing her as the human-embodied Shuri. Then she dives into air and her body transforms into a that of a crow, and this crow’s body is juxtaposed with the head of the Black Panther. The sequence ends with her transformation back to Shuri. In the process of these movements and metamorphoses between and in juxtaposition to different life forms, we learn of her special access to the realm of the Djalia, the wisdom and skills of those who came before her. She is figured here as a kind of Cyborgean shaman for her people, highlighting the role of responsibility in her relation to technoscientific change and time.

In this particular sequence of frames, the high-tech future is represented by the geometrical grid of the buildings bathed in a golden light. Layered upon and looming over this grid-like urban environment is the figure of Shuri, the browns, blacks, and blues of her various human and non-human figurations emerging and contrasting strongly with this golden light. It is as if the hard grid of the city is a dream bathed in light, while the dream-like transformations that occur across the pages are hard-edged and real. In addition, Shuri is both mechanically enhanced and connected to the bodies of crow and panther: there is no real separation between these realms for Shuri, who uses her wings to flow and play between the straight angles of the cityscape. The graphic form in general and the white space of the gutter here allow for these transformations between human and non-human to almost effortlessly flow like Shuri herself riding the wind. The comics sequence plays on the ambiguity of Shuri’s identity: she cannot be said to be ‘human’ or ‘crow,’ to be ‘ancient’ or ‘future,’ to be ‘high-tech’ or ‘natural,’ but rather to vacillate and exist in liminality. The gutter as the blank space where transformation happens enacts and showcases precisely the possibilities of liminality, and thus gives a kind of form to what the frames are communicating: other possibilities of identity formations that do not conform to the ‘mechanistic metaphysic’ (Ghosh 2021: Loc 4139) of humanism. As with the graphic version of Parable, in Shuri the formal qualities of comics, including compression, colour and closure, allow for the intricacies of more-than-human life to manifest on the plane of the page.

The philosopher and anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose, basing her philosophy on Indigenous Australian knowledge systems, emphasises the need for alternative understandings of time as necessary to fully face and rethink conceptions of identity in the face of climate crisis and species extinction, now and in the future. She writes that ‘in place of the abstracted, disembedded, disembodied absolute time posited by Newton’—in other words, the singular time story of humanism that I mentioned in the beginning of this essay—we need scholarship and art that ‘focuses on the embodied and embedded qualities of time’ (2012: 128). Her point is that such embodied time is fundamentally ethical because, as she writes, ‘embodied time is always a multispecies project … [a]ll living things owe their lives not only to their forebears but also to all the other others that have nourished them again and again, that nourish each living creature during the duration of its life’ (2012: 131). The sustenance of bodies and life requires a whole system of species entanglements, and if this seemingly simple reality of life were to occupy the center of human understanding of past, present, and future, then ‘multispecies knots … may be understood as … a site of encounter and nourishment’ (Rose 2012: 131). We would literally learn to ‘see’ the tree in ourselves and vice versa, opening for multispecies relationality as an ethical project for the survival of all beings, and embedded in this ethics is responsibility for future generations. This is an extremely apt description of the figuration of the shape-shifting Shuri throughout her narrative, and much like Lauren’s coming to understand herself via the connections and disconnections between herself and the dying dog, Shuri’s many encounters work to shape an ethics of the future where multispecies conceptions of embodiment open for new/old ways of knowing that shift the focus from human-centred to complex interspecies visions.

The graphic figures of Lauren and Shuri are figurations for embodied time. Tracing the implications of their figurations, as I have done in this essay, we see that their many embodiments on the page can be traced so as to see how they become instrumental towards knowledge building for thinking futuristically, for rethinking how self and other can and should signify ethically in the future, in times of crisis. As such, these two works exemplify how the comics form is and can work to be a site of necessary engagement, a popular culture form that communicates to many different kinds of audiences’ alternative systems of knowledge that we must take into consideration as the future unfolds. In other words, through recognising speculative creators’ use of figuration, and then ‘unpacking’ these figurations as they relate to worlding, power, embodiment and ethics, the comics form functions as a site where it is possible to offer productive interventions into an uncertain future.

REFERENCES

Bastian, Michelle (2006), ‘Haraway’s Lost Cyborg and the Possibilities of Transversalism,’ Signs, Vol 31, No. 4, pp. 1027-1049.

Braidotti, Rosi (2022), Posthuman Feminism, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Butler, Judith (2004), Precarious Life, London: Verso.

Bulter, Octavia (1993), Parable of the Sower, London: Headline.

Chute, Hillary (2008), ‘Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative,’ PMLA, Vol. 123, No. 2, pp. 452-465.

Duffy, Damian and John Jennings (2020), Parable of the Sower, New York: Abrams.

Fabricius, Charlotte Johanne (2021), Super-Girls: Girlhood and Agency in Contemporary Superhero Comics (PhD Thesis), University of Southern Denmark.

Grosz, Elizabeth (2002), ‘Feminist Futures?,’ Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 13-20.

Haraway, Donna (1985/2016), A Cyborg Manifesto, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, Donna (1997), Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium, New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna (2016), Staying with the Trouble, Durham: Duke University Press.

Hirsch, Marianne (2004), ‘Collateral Damage,’ PMLA, Vol. 119, No. 5, pp.1209-1215.

Ghosh, Amitav (2021), The Nutmeg’s Curse, Chicago: UCP Press. Kindle edition.

King, Edward and Joanna Page (eds) (2017), Posthumanism and the Graphic Novel in Latin America, Chicago: UCP Press.

Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014), The Sixth Extinction, New York: Henry Holt.

Menga, Filippo and Dominic Davies (2020), ‘Apocalypse yesterday: Posthumanism and comics in the Anthropocene,’ EPE Nature and Space, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 663-687.

McCloud, Scott (1993), Understanding Comics, New York: Harper Collins.

Okorafor, Nnedi (2015), Binti, New York: Tordotcom.

Okorafor, Nnedi (2019), LaGuardia, Milwauki: Dark Horse.

Okorafor, Nnedi et al (2020), Shuri: Wakanda Forever, New York: Marvel.

Rose, Deborah Bird (2012), ‘Multispecies Knots of Ethical Time,’ Environmental Philosophy, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp.127-40.

Schalk, Sami (2018), Bodyminds Reimagined, Durham, Duke University Press.

Scherr, Rebecca (2013), ‘Shaking Hands with Other People’s Pain,’ Mosiac, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 19-36.

Ursini, Francesco-Alessio et al. (ed) (2017), Visions of the Future in Comics, Jefferson: McFarland.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey