Bringing Brophy Back: In Conversation with Kate Levey

by: Kate Levey & Anna Backman Rogers , May 23, 2019

by: Kate Levey & Anna Backman Rogers , May 23, 2019

MAI: Hi, Kate.

KL: Hi there, Anna.

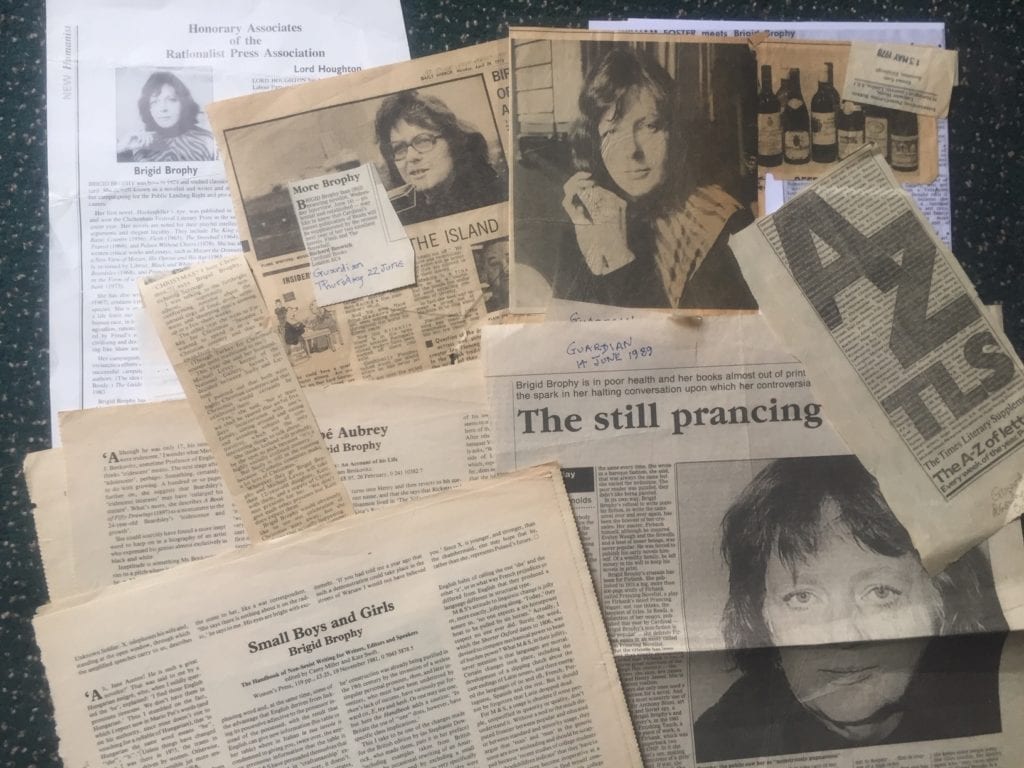

MAI: The last time we corresponded was for the second issue of MAI, last year, about your ongoing battle to get your mother, Brigid Brophy, a Blue Plaque from English Heritage (which I am now also really cross about). Some of our readers may be unfamiliar with your mother’s work, which was so extensive and really, I must say, avant-garde. Could you tell us about her and her life and why she is so special?

KL: I hope I’ve said how glad I am of your interest, and that having no expert knowledge of Brigid Brophy I necessarily speak from a filial perspective. There is so much to cover that this is only a start. I will try to be succinct!

To someone who enquired about Brophy recently I sent the following:

Brigid Brophy’s career started with a bang in 1953 with her prize-winning first novel, Hackenfeller’s Ape. She went on to publish both fiction and non-fiction and became an outspoken critic on topics as such as marriage, religious education, and prison reform. She turned herself into a skilful campaigner, appearing on television, on radio and in newsprint; her views were thought to be either courageous or outrageous: she certainly did not dodge the opprobrium of the establishment. In the 1960s and 70s, Brophy was a go-to provider of controversial copy for any editor seeking to whip up interest: Brophy was prominent; in fact famous. Hers was a household name associated both with trenchant views on contemporary topics and serious intellectualism.

MAI: That’s a wonderfully succinct summary of her contemporary impact! I have so many questions, but perhaps a good place to start is in relation to Brigid Brophy’s politics.

Your mother was, as you’ve said, an activist and a campaigner for many causes, but specifically women’s rights and the rights of animals. She also had very unconventional and challenging ideas for the period in which she was campaigning and writing on marriage, war and religious education. What was your experience of this? Her views seem strikingly relevant to and in tune with our contemporary moment as well. It is unbelievable people aren’t talking about her work more.

KL: In the twenty-first century, we are the beneficiaries of the impressive legacy of this trailblazing woman writer who has been scandalously under-appreciated, thus lost to history.

Brophy’s achievements which have current resonance are:

- She kick-started the modern animal rights movement with her 1965 article The Rights of Animals published in The Sunday Times. A pioneering vegetarian and later vegan, Brophy’s articulate thrust against vivisection, meat-eating and factory-farming was crucial in laying out the ground for the huge take-up today of interest in ethical animal treatment.

- She published the radical novel In Transit (1969) in which gender fluidity was explored by means of a linguistic romp through an airport with a gender-ambiguous narrator. Brophy was a well-known proponent of gender equality, and specifically, of homosexual rights; she opposed suppression in all its forms. Her vehement liberal and left-wing views were as reviled as they were admired.

- She took on the cause, with Maureen Duffy, of author’s rights—devoting seven years to a battle against governmental apathy and dispute; this culminated eventually in the payment of Public Lending Right (1979 Act) to authors whose works were borrowed from public libraries. Forty years on, this payment system is still in successful operation.

MAI: All of these achievements alone would be considerable enough for her to be remembered formally in British culture, but she also was an incredible writer. You’ve said your mother wrote both fiction and non-fiction. Do you see her work in both formats as related? Do you have a favourite book she wrote? I’ve recently finished the absolutely brilliant and vivid The Finishing Touch (1963; 1987). I see somebody described it as a ‘lesbian fantasia’! What were her passions and interests when it came to writing? What, for you, defines her style and concerns as a writer?

KL: The Finishing Touch is delightfully and lightly lesbian; the prose is suffused with air, rather like Françoise Sagan’s, but I suppose principally it’s Firbankian. Brophy’s analysis of Ronald Firbank, Prancing Novelist (1973) remains unchallenged as the critical biography of Firbank, so that’s an illustration of the nexus of her fiction and non-fiction.

MAI: Do you have a favourite piece of writing by your mother? Where would you recommend that a Brophy novice should start?

KL: I usually advise Brophy beginners to try The King of a Rainy Country. First published in 1956 and reissued in 2012 by Coelacanth Press, it’s as fresh as it’s funny and deep. Perhaps there is greater sophistication in The Snow Ball, (1964; now available from Faber Finds), which Brophy considered to be a masterpiece. But her work defies easy categorisation; it is too various to define deftly except by acknowledging its elegance and originality, which is why I include a brief description of each of her novels on brigidbrophy.com.

MAI: That’s a wonderful resource for our readers, Kate. Thank you. I read somewhere (I think it was an article in the TLS) about the conference dedicated to the exploration of Brophy’s work in 2015. Did you attend? Do you think interest in your mother’s work is growing again?

KL: Yes, there was a successful Brophy conference in 2015, marking 20 years since she died, with two academics from the USA attending, and other people who, between them, paid tribute to the scope of Brophy’s talents. I could expand about the conference, however, with apologies for appearing self-centred, my contribution was a piece about my parents’ letters to each other. In it, I noted how my mother wrote to my father, circa 1954, before they married: ‘Until a year or two ago, I was at least 50% homosexual, and this was the half I acted on’.

I thought it interesting that she and my father (the art historian Sir Michael Levey, Director of London’s National Gallery) had from the outset a full understanding. These letters to my father which I am currently editing for potential publication show Brophy writing to him about her lesbian attractions, among other matters. My mother’s unconventional sexuality, as well as her quite unique stance on almost all topics, had a huge impact on me as I grew up. It was not always easy to take it in my stride, but I never questioned it. (When The King of a Rainy Country, which plays mildly with sexual ambivalence, was re-issued in 2012 I spoke about a school classmate who had memorably once asked, “Is your mother Enid Blyton?” That gross misunderstanding was not favourably received by me or my parents!).

But yes, since the Brophy conference there has been discernible new interest, and I welcome that warmly. It is a halting bandwagon, however, and Brophy is still underrated and overlooked. Reasons proffered for her lack of ‘presence’ are many, but in my view, she is rejected by current mainstream culture, which cannot deal with her sheer force. It is a shame that mordant humour and piercing intelligence are still regarded with suspicion, arguably all the more if they reside in a woman.

MAI: Do you think your mother faced specific challenges at the time she was writing and campaigning because of her gender? She’s obviously such an important figure in women’s history, especially, and deserves so much more recognition. Do you think this is part of a grander narrative by which men often take credit for the work of women or write them out of history entirely? The saga of the Blue Plaque (as I shall now refer to it) seems indicative to me of the general lack of care and interest extended to women’s history and writing despite the efforts of many women to rectify this situation.

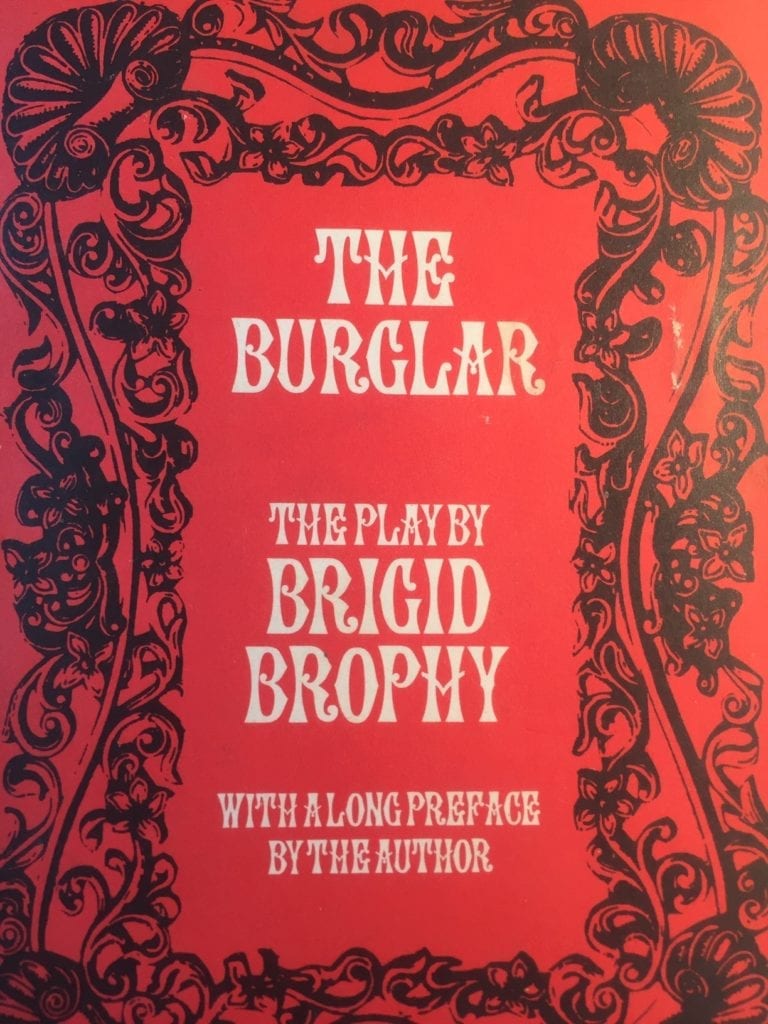

KL: There’s no doubt Brophy met resistance due to her gender; that she recognised it is explicit in the preface to her published play The Burglar (1968) where she remarks that the ‘gist of the notices of The Burglar was that Brigid Brophy has a “combative” and “pugnacious” disposition”.

She believes a fictitious playwright, Tim Smith, would have received less disparagement of his character. She develops the theme considerably in a multi-pronged argument and states, ‘A woman who engages in any public or national activity is forcibly assessed on the sexual-attractiveness scale.’

MAI: Pow! Not much has changed, eh? How would you like your mother to be remembered, Kate?

KL: A literary biography of Brigid Brophy is long overdue, as of course is a Blue Plaque! She would not have cared about one, but I believe she merits that recognition.

In my view, Brophy’s paper archive needs a proper repository, and I regret that despite its being up for sale, no-one has actually negotiated for it. I do not wish to donate it as it represents so much truly hard graft on Brophy’s part.

MAI: Yes, I can quite understand that! I’m very surprised this archival material has not been purchased already by an institution invested in women’s culture, actually …

Interestingly, I noted that there are three or four of your mother’s books in The Second Shelf in Soho. They were even signed by her. I hope this is indicative of our wish to Bring Brophy Back … and surely that biography is on the way. It’s been so lovely talking, Kate and I really look forward to future work and collaboration on Bringing Brophy Back.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey