Breaking Open New Worlds: An Interview with Bishakh Som

by: So Mayer , March 30, 2023

by: So Mayer , March 30, 2023

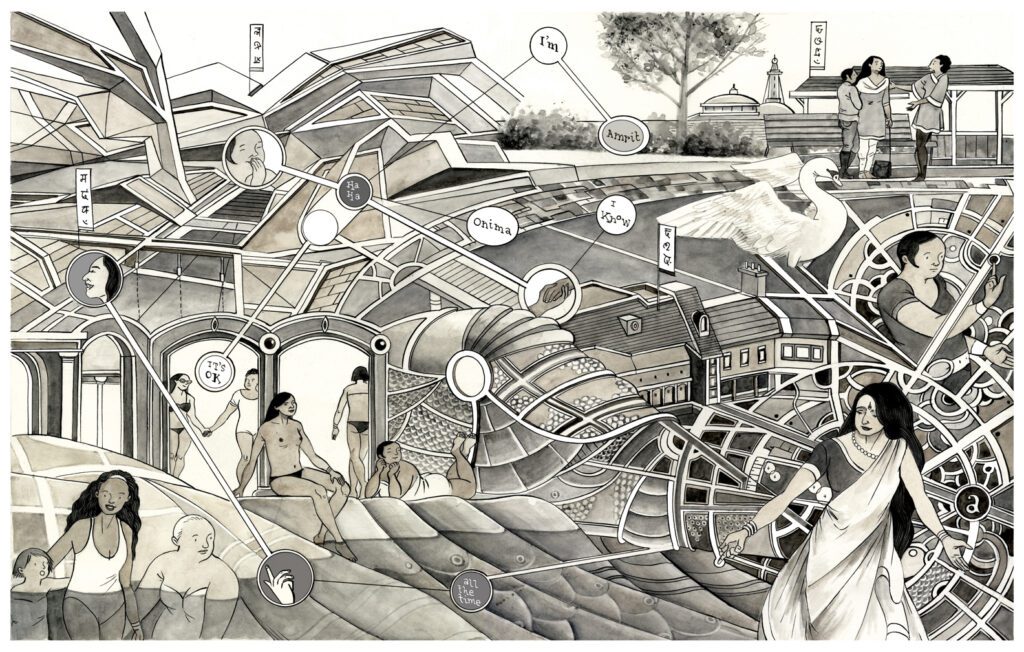

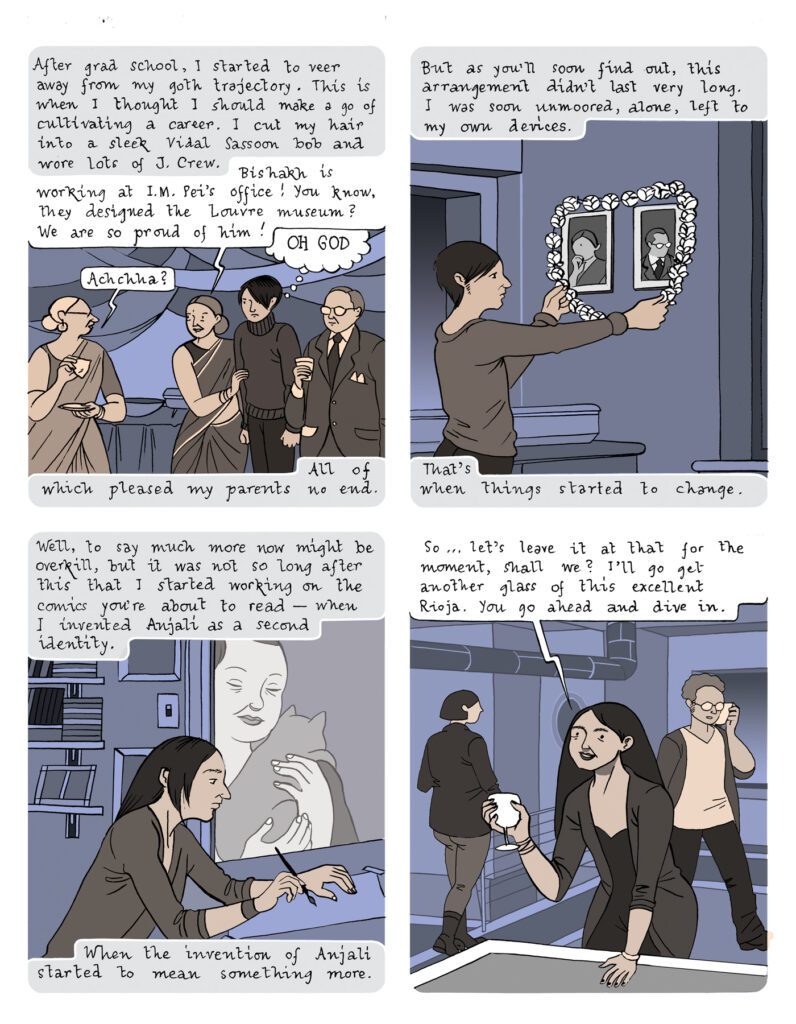

In 2020, Bishakh Som exploded like a firework into the worlds of independent graphic novels and the new trans literature, with two books: Apsara Engine, a collection of dreamily interlinked spacetime-defying short stories of bodies, maps and being, published by The Feminist Press, and Spellbound: A Graphic Memoir, about an architect called Anjali who quits her job to work on a graphic novel, published by Street Noise. Since her Xeric-winning first collection Angel (2003), Som’s work has appeared in the New Yorker, We’re Still Here (the first all-trans comics anthology), The Georgia Review, Beyond vol. 2, The Strumpet, The Boston Review, Black Warrior Review, VICE, Buzzfeed, Ink Brick, Hi-horse (which she co-edited), Blurred Vision, Pood, Specs, The Brooklyn Rail, and Graphic Canon vol. 3 (Seven Stories Press). You can see samples of all of these projects on her website.

*

So Mayer (SM): Apsara Engine was one of the first books that I got in lockdown. For me, it has such a strong relationship to spring 2020 and the pandemic. Did you get responses from people saying, ‘this is really speaking to me in this moment?’ How do both Apsara and Spellbound seem to you when you look back at them from the moment of publication? Because both projects evolved over quite a while.

Bishakh Som (BS): With Spellbound, a lot of it is about the day-to-day discipline of becoming an artist, and the character—who’s me—swapping her full time job in office to focus on her art at home, and being housebound, and the emotional instability that comes with that. It was funny that, as it came out, everyone else was forced the very same thing, and stay at home and become a sort of hermit, or hermitess. So, it seemed to be resonant in that way.

Apsara was the opposite because it’s more about creating worlds. It’s about an opening up of possibilities, mental spaces, and physical spaces, but ones that are engendered by trauma. Or by joy, it’s hard to separate the two things. It resisted, in some way, the confining aspect of the pandemic. And it did make it a little sad because it’s about breaking open new worlds, especially in ‘Swandive.’ What was happening in the world was the polar opposite of what Apsara was proposing to the world.

SM: Because you mentioned ‘Swandive’… I’m interested in the contrast between the seeming linearity and unity of Anjali’s narrative in Spellbound and then the density of possibility within each of the stories in Apsara Engine. Was there ever a moment when you thought about expanding each story into a full-length book?

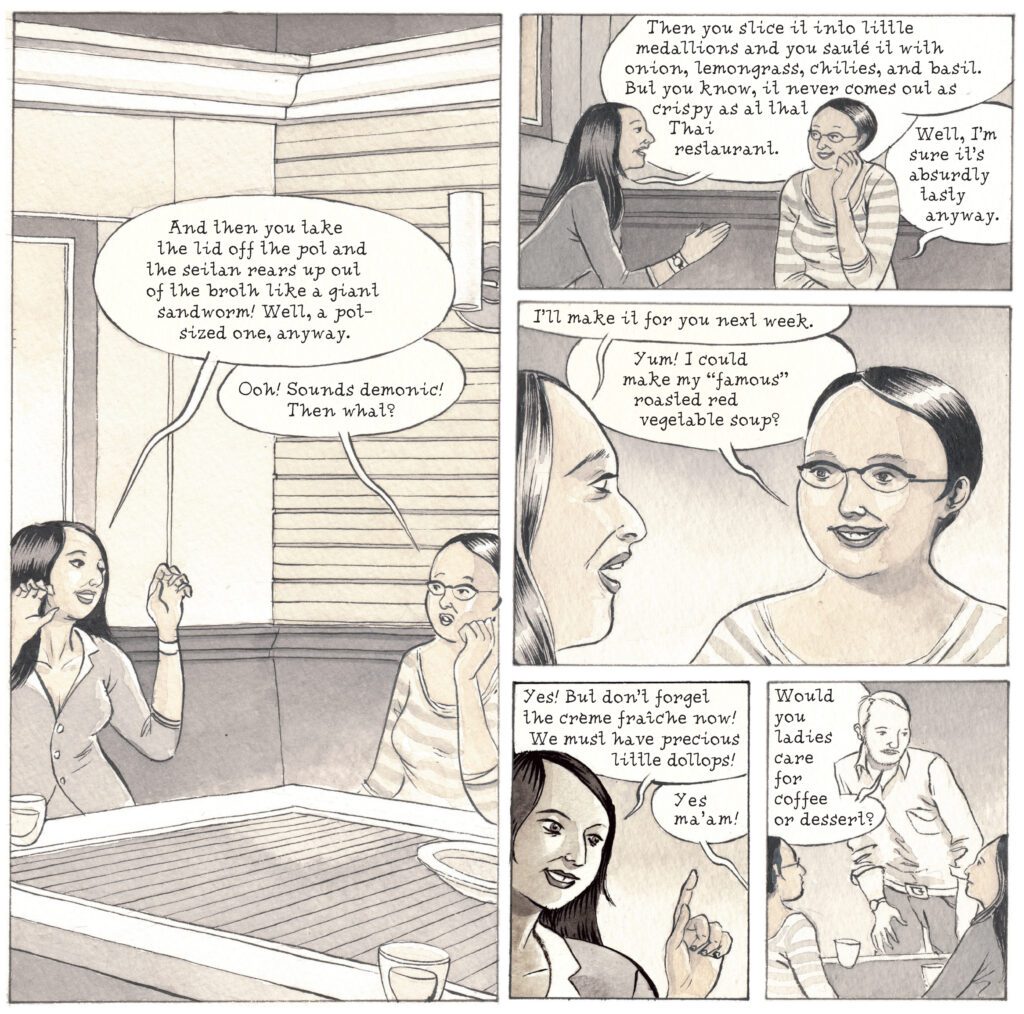

BS: Most of the stories in Apsara are self-contained and don’t lend themselves to a sort of elaboration or extension. The one story that I did have ideas for expanding was ‘Meena and Aparna,’ which doesn’t really get that much love. I love those two characters, and I love their friendship. That’s one of the earlier stories that I wrote before I came out as trans. And you can tell in that story because it hints at queerness without ever being explicit about it. Clearly, I was approaching it, like an asymptote: approaching but never touching. The story is doing the same thing. But I want to see, what would happen to Meena? Can she say she’s queer? How does their friendship develop? Do they become lovers?

I was looking back through old documents on my computer, and I discovered a script I wrote for an epilogue for ‘Meena and Aparna.’ At the beginning of the story, Aparna talks about making seitan. So, the epilogue I wrote was the two of them in the kitchen, and it would be a recipe like the one at the end of Spellbound, but it would be a comic in which Meena and Aparna are in the same space, having a bit of a banter. I didn’t quite finish it, but I did make the attempt to expand that universe. Maybe one day they’ll reappear in their own adventures.

SM: I love the idea of a cookbook where it’s characters from your stories cooking recipes! Because the food in Spellbound is so great. How do you convey smell and taste to a reader? Is that partially in the switch from monochrome to colour?

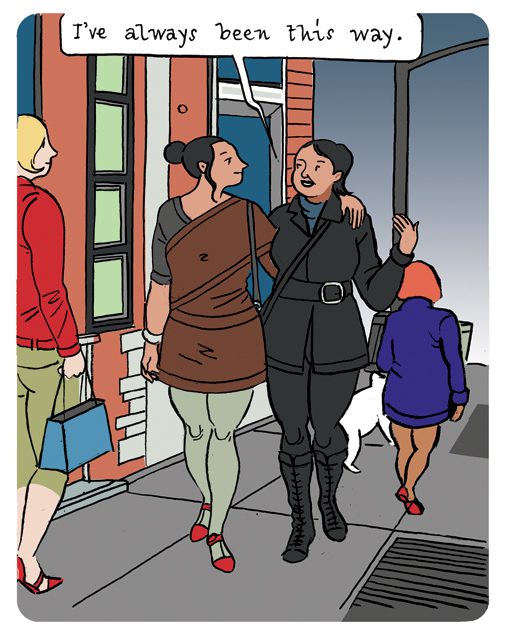

BS: As far as monochrome versus colour goes in Spellbound, that was to do with the difference between my real life and the semi-fantasy life of the memoir. When I’m drawing myself as me, it’s in monochrome, and the colour portion of the book is fantasy: which is real, and which is not real? My initial inclination for using digital colours was to have a clean graphic look. Most of the work I’ve been doing up to that point was in the style of Apsara, dreamy watercolours. I wanted to see if I could do something with a crisper new look, almost Tintin-style. I know we’re not supposed to reference him anymore, but he was a formative part of my artistic childhood experience, so I have to acknowledge that for better or for worse.

It just seemed to lend itself to the diary comic format. I could have done it in linework, but I took some time with the colour, and it gave it that whole world of detail. There’s one panel I like, which has these jars of Marmite and mustard on Anjali’s kitchen counter. Those are the things that visually I really get worked up about; to me, they connote a whole world of other references, whether they’re olfactory or not. Colour brings that level of grounding and detail.

SM: As well as Tintin, what else were you reading or looking at that stayed with you?

BS: I have a whole collection of Indian comics by Amar Chitra Katha (ACK Comics). These are things that I read when I was four or five, things my parents bought for me. So, they’re kind of to blame for my later trajectory in life, and possibly for being trans—but that’s another story altogether. I don’t know how much I took away from those comics, but at least in terms of learning the language, they were very formative for me. Being a person of a certain age, I also read things like Archie comics, which are ridiculous, but it says something that I was never interested in Archie and Reggie and the male characters. I was always like, I wish I was a mix of Betty and Veronica, and I wanted to see them go off and have their own adventures!

In high school I was drawn to certain artists but I’m not sure how much of their work shows up in mine: Klimt, Edward Gorey, Egon Schiele, Mary Cassatt. Beardsley was a big favourite. Of comics artists, it’s particularly the brothers Hernandez. Love and Rockets has had much more of a visual influence on my stuff than any other work. Dame Darcy’s work, I love it a lot. It gave me a window into what comics could be like.

SM: What was your personal trajectory with the indie comics world? Did it offer possibility and creativity? Or is it something that you came to later, via doing your own work?

BS: There was a moment in the 90s where discovering things like Love and Rockets was eye-opening. And Dame Darcy. Tank Girl and then later Diane DiMassa and Hothead Paisan. That was the spark that led me to try and make my own comics, or to give my comics a voice that they didn’t have before that, but it wasn’t a direct lineage. There was a sense that if there was a ferment, if there were enough people doing it, I could be part of that, too.

But once I started going to comics conventions, the ones that were indie- or alt-oriented, I found that culture very toxic. A lot of the work, at least in the States, seemed to be dominated for a long time by these really nasty cis boys, very misogynistic, transphobic, and homophobic, played as if it was satire. I gravitated toward the women cartoonists, but it just didn’t seem like there were enough of us, so I gave up for a while. At this point, I didn’t know anything about trans culture, that world wasn’t open to me.

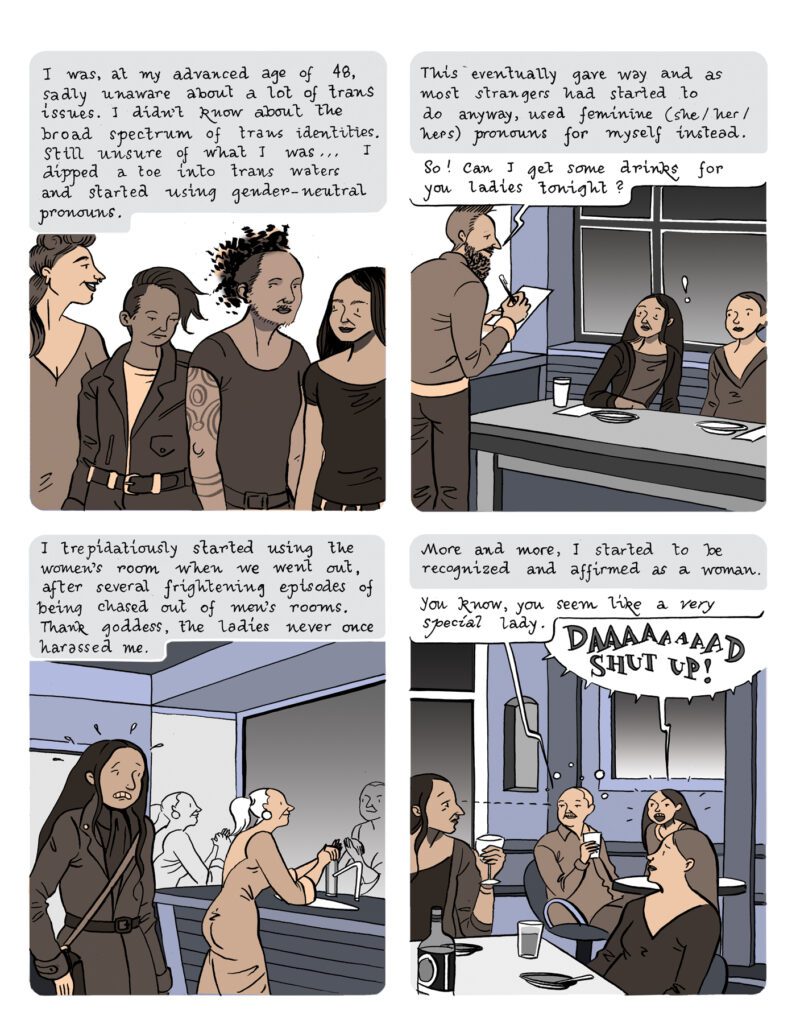

I dropped out, but I kept making my comics. I operated in a vacuum for a long time, possibly to my benefit. While writing the stories for Apsara, I stopped reading comics altogether because I didn’t want to compare myself to anybody, and because I thought that toxic culture was still lingering. I’m getting back into trying to immerse myself into comics culture, because the tide seems to have turned somewhat. There’s so many trans and non-binary cartoonists, and cis women and queer women and genderqueer people, who have taken over a lot of the scene and I have really firmly aligned myself with them. I feel a great sense of security and stability, that we form a bulwark against whatever lingering toxicity is a hangover from that miserable era.

SM: One of the powerful aspects of Spellbound is that Anjali, who is trying to get her book out, lays bare the process, chewing over the question of publishing with trusted independent presses, or trying to get a mainstream publisher to get a bigger audience. How has your experience been?

BS: I’m so happy to have been picked up by The Feminist Press. I feel like before it came out, and even after, nobody really knew what to do with Apsara as a book, it wasn’t marketable, because it was very nebulous. The Feminist Press saw the potential in it, and liked the nebulousness, but they also tied it together with more of a structure, which I couldn’t do myself. I don’t think any other publishers would have had the patience or the vision to be able to do that. ‘Swandive’ as a story would not have existed without them. They said, ‘would you write another story that’s more from your point of view now as a trans woman?’ And without that story the book would not be half the book that it is.

When I initially sent Apsara Mark One to publishers, I was aiming for the people that I thought would make me a star like Fantagraphics, Drawn and Quarterly or Top Shelf—none of them knew what to do with it. They all said no, and I thought, I’ve failed in the one thing that I set out to do with my life, so I was pretty down. But it took enough time between when I went out and now for things to have evolved to the point where I think, if Mark Two had gone out, they would have been all over it, because things have changed so much in those seven or eight years. Although the more mainstream publishers could have maybe gotten the book out to more people, it did great with The Feminist Press. That’s my sense of cosmic balance: it wasn’t my time back then. I think the goddesses were waiting and saying, you must choose wisely. These people know what you are deep down, and it’ll just take you some time to realise yourself.

SM: In the framing narrative of Spellbound, there’s this beautiful description of you almost drawing yourself into being through Anjali, which suggests that as artists, if we trust our unconscious, it doesn’t just produce work, it produces ourselves. Can you talk about that process of bringing this self to this surface?

BS: As to writing myself into existence, I think, before the ‘Swandive’ era, a lot of the stories were hinting at possibilities without even knowing what those possibilities were, hinting at queerness. And as a person who didn’t think of themselves as queer at that time, it was like, I’m not sure if I’m allowed to do this, which is why I was oblique about it. Hence the existence of these hybrid creatures in the book, like Kiki the dog in ‘Throat,’ Bird Woman in ‘Love Song,’ and the creatures that defy categorisation or definition. At the time, I didn’t quite know why those characters were appearing in my work—but the brain has its way of sending you messages! That idea of crossing genres, in terms of whether one is human or not, really scared me. In retrospect, it wasn’t fear that I was contending with, but the reality of an essence that I was missing and afraid to confront.

The creatures that I was creating, the characters I was writing, were telegraphing the way ahead for me. Even if I couldn’t name the past, at least it was being sketched out. For me, all the queerness in the book that is unspoken, all of that feeds into the formation of a character who eventually becomes me. Apsara, for me, it was all about a process, not only writing stories, but a process of documenting the movement towards me.

SM: With Apsara Engine, it felt to me like that was happening in the form as well, that it’s trans storytelling, because it’s multi-dimensional, it’s mobile in this really creative and exciting way. Stories are constantly opening up to feel like they could go somewhere else entirely, and it’s often at the level of the word-image relationship being expanded or exploded. What excites you the most about that experimentation?

BS: I’d started doing stuff like that before Apsara, where I was doing experiments between how text and image synchronise. I hadn’t ever seen comics work that was doing that. I thought, what would happen if it untethered, what third or fourth meaning could come out of the interference between the two? And I got bad feedback that it didn’t make any sense. So I shied away from that for a while, and that’s why I tried to write more conventional narratives. Hence things like ‘Meena and Aparna,’ or ‘Pleasure Palace,’ or ‘I Can See It in You’ in which image and text are bonded together, and but not in the service of telling a conventional narrative. I still really enjoy that kind of work.

But I went back into it, because I had more confidence, hence ‘Come Back to Me,’ where the image and text seem to be married for a little while, and then they float apart. In ‘Love Song,’ there never was a marriage, it was just this flirtation on the astral plane, and you make of it what you will. It’s a different issue if it’s dialogue, like if it’s Meena and Aparna talking to each other; they have body language, and they’re performing theatre in a way. Their facial expressions hint at things that may or may not be spoken. Image and text can dance with each other without mimicking each other; it creates something that is only possible in comics.

SM: Part of that dance and experimentation, for me as a reader, is that it shapes a pushback in your work against the Eurowestern binarism that if there are gods, it must be fantasy or magic realism, toward finding a language for an immanence of the divine in the everyday. Can you talk about the lived place of goddesses and other presences in your work?

BS: I think so much of that comes from my childhood and my upbringing. A lot of that excess divine femininity turned me into who I am, to some degree. So, thanks again, mom and dad. I talked a little bit in Spellbound about how, as a Hindu, it’s very problematic to say that I’m a Hindu, given the current prime minister of India and the Hindu nationalist agenda that he has been subjecting India to; it’s very difficult to say you’re a Hindu without aligning yourself to that tendency. But it is who I am. So much of that comes from how my parents brought me up as Bengali; our focus was on two goddesses in particular: Kali, and another manifestation of hers is Durga. And then my personal favourite, because she also represents art and music, is Saraswati, who rides a swan.

These presences—visually, these images of goddesses—were always around me as a child. So that seeped into me very, very deeply, and was part of my everyday existence. It was a very spiritual and visual experience for me, rather than one that had to do with dogma. It was a sense of the beauty and wonder and divine energies of these goddesses as something that one could channel if one was so inclined.

It’s right in the title: apsaras, who are in a lot of Hindu mythology, they’re the showgirls of the heavens, these heavenly courtesans, dancing and performing. There’s a legacy of performance with South Asian trans women, and I think of them as apsaras too. I wanted to take these characters who were inhabiting the fringes of mythology and bring them into the spotlight and show that apsaras can manifest themselves as people and as beings on this earth. They don’t have to be in this other realm, but rather, they can be part of this existence, and they don’t have to be necessarily benign presences, either. Because a lot of the stories of apsaras are about disruption. They come to fuck shit up—for the better, I think.

SM: While we’re talking about divine presences, I want to ask about Ampersand, Anjali’s cat in Spellbound, because he’s like a co-protagonist.

BS: He’s like a Greek chorus. When Anjali is wallowing in self-pity, Ampersand is in the background going, Get over yourself. It’s the kind of self-criticism I would have, when I was channelling my Anjali essence and being similarly stuck, artistically or emotionally. Cats, for me, are magical. It’s a trope that has been overdone, but I can’t get over it. To me, they’re part of a divine essence of this spiritual web that we’ve spun in our little households. They resist being talked about too much. Any human interpretations that we try and impose on them they can very easily escape, which is why I love them so much.

SM: Toward the end of Spellbound, Anjali’s parents come in as dream visitations and sit on her sofa, and they tell her they love and support her artwork and her queer self. We so rarely give ourselves those gifts: what was it like giving yourself this moment with your parents through Anjali and hers?

BS: It was pretty great. It’s something I’d wanted to do for ages. Even before Spellbound was a book, I wanted to make manifest the possibility that my parents would accept who I am now, as an artist and as a trans person. Drawing that episode made that real for me. It was a way to invite them in and make that possibility more open to myself, and maybe to them.

Even though in Spellbound I show how they wanted to direct my life as a young person, and what their ideas of success were, I wish to some degree that they were still around, so I could say, I know I defied your directives, but I’m in so much of a better place now, doing exactly what I wanted to do, and making a success of it. Dad certainly wouldn’t have admitted to having made a mistake, but I would hope that having cast off this mortal coil, they would have been in a place where such concerns would become petty, and that they’d say, you’re doing a great job and you’re being who you are. I would have sucked as a cis dude, trying to be a doctor, that was clearly a recipe for failure. I probably wouldn’t even be here now, as a living person. This was what I had to do to survive. It’s not only a question of finding a voice, it’s a question of survival.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey