Biblical Domestic

by: Sarah Lightman , March 30, 2023

by: Sarah Lightman , March 30, 2023

My series of watercolour paintings, Biblical Domestic (2021–2022) feature lightly depressed women from the Bible escaping historical paintings, only to become trapped in my unending household chores during the Covid lockdowns (2020–2021). My artwork recorded my own experiences and that of many mothers of young children during lockdown. In a study by researchers in Bristol and Berlin using survey data covering more than 2,000 couples aged between 24 and 54, between March and September 2020, ‘Couples with school-age children and couples with a 0- to 5-year-old were already clearly retreating to a more traditional gender division of housework.’ [1] My artworks reflect that this happened in my own household and that it caused me a great deal of distress.

During lockdown, I couldn’t leave the house to visit a gallery, so I had to bring the gallery into my home. Nor could I go to my art studio. I could only dream of a space and time, to make work in the future. These A3 watercolours are works in progress, and when I have the time and space, I plan to make them into much larger oil paintings. These new paintings will also mark my journey towards being a painter and away from the domestic-sized pencil drawings of my graphic novel.

As I was making this series, I have been looking at British artists who have interwoven self, Bible, and contemporary life in their work. Two of the artists I will discuss went to The Slade School of Art, where I studied for my BA and MFA.

Winifred Knights was born in 1899 in London, and in 1920 she became the first woman to win the prestigious Scholarship in Decorative Painting awarded by the British School at Rome. Her prize-winning entry was The Deluge, [2] now in the Tate Gallery, London. The painting was made just after the end after the First World War, a time of great uncertainty and destruction. The Deluge interweaves Knight’s own personal experiences, and the biblical narrative. The painting is about being saved, and being safe, even amongst the destruction of the world. After The Great War, and after the great flood, there is hope. People can be safe if they can reach the higher ground, even those outside of Noah’s Ark.

In the painting, Knights includes a self-portrait, as well as the faces of her friends and family. By placing herself in the image, Knights opens up a world of empathy and possibility. In Genesis, the story is all too focussed on the selfish figure of Noah, who is a less-than-impressive character. In contrast, Knights has painted herself and her loved ones, making their experiences the focus here. It is them we follow with our eyes: they are our heroes, we will them to survive. Knights brings this story into a real world, inhabited by real people, not a distant anonymous, mythological universe from thousands of years ago.

Another artist is Stanley Spencer, born in 1891, and famous for his paintings of biblical events happening in his hometown of Cookham. His painting, The Resurrection in Cookham Graveyard, [3] is 9 feet high by 18 feet long, and is also held in The Tate Gallery. In this painting, there are many figures rising from their graves. The figures are not the dead rising, however, but again contemporaries of Stanley, all very much alive at the time he painted them.

There are another two paintings by Spencer I want to mention, including one that touches on stories from The New Testament, The Bin men or The Lovers, [4] painted by Spencer in 1934. A dustman is returning home to the arms of his wife who lifts him. He appears as Christ ascending to heaven, or the Resurrection, even the Adoration of Jesus with the onlookers offering gifts, a cabbage leaf, teapot and jam jar. Spencer also painted The Dustbin, Cookham (1956), [5] in which a woman is putting out the rubbish.

I chose these two Spencer paintings as I too paint about putting out the trash. As I bring this daily, unpleasant, and smelly task into high art, I also introduce a feminist reading. I based my painting on a 1659 painting by Elisabetta Sirani, Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great. [6] Sirani was a groundbreaking painter and printmaker, born in 1638, who established an academy for other women artists.

Timoclea’s story is told by Plutarch. In 335 BCE Alexander the Great and his forces took Thebes, and Thracian forces looted the city. After a captain of the Thracian forces raped Timoclea she was determined to have revenge. The captain later asked if she knew of any money had been hidden. Timoclea told him there was money hidden in a well in her garden. She then pushed him in and flung heavy stones after him.

In my painting, Timoclea (2022) travelled from Italy to Camden, London, and ‘upskirts’ her rapist in the process. As I wrote on my Instagram post on February 1, 2022:

With the refuse men only coming every alternate Tuesday morning to empty the black bins, Timoclea finds it a struggle to fit in all her rubbish. She often has to give everything a big shove. ‘Refuse’ from my ‘Biblical/Historic Domestic Series’ where women escape master paintings only to be trapped in my household chores.

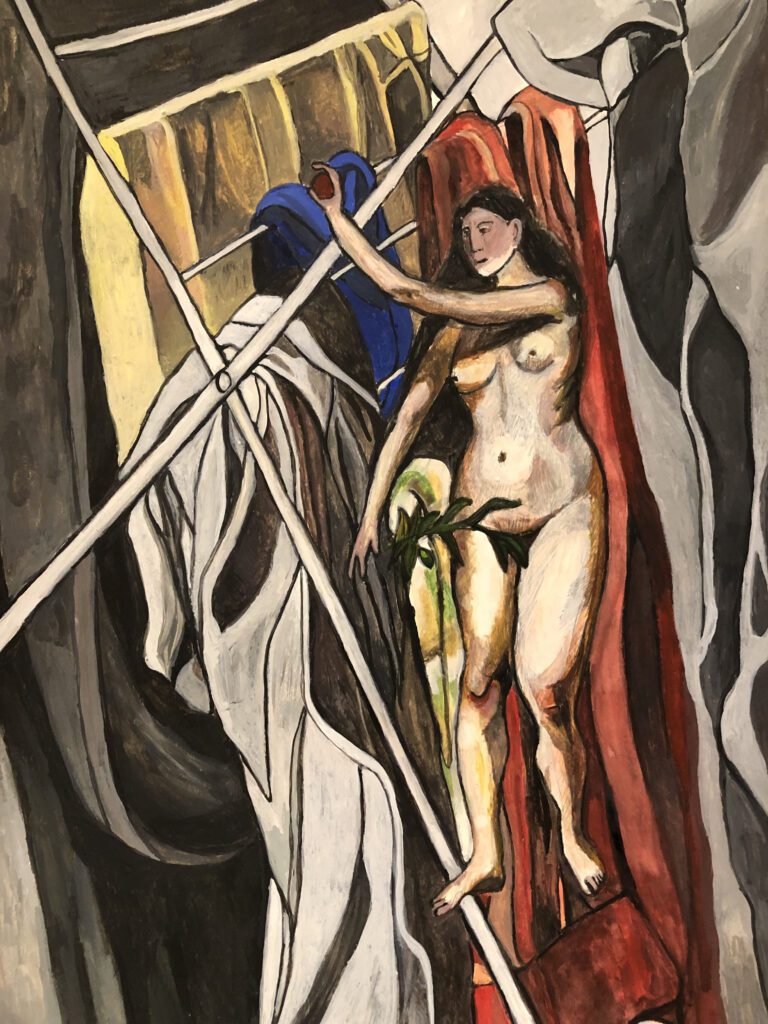

In Dressing Eve During a Pandemic (2021), Eve is borrowed from a painting by Titian entitled The Fall of Man (1550). [7] In Genesis, Eve’s strivings for knowledge are symbolised by reaching for an apple. In the 21st century, the apple of intellectual and creative endeavours is replaced by clothing, the desire for which, as you might recall, came about from eating the original apple. If, as Eve in Hampstead, London, during the lockdowns, I might want to reach for any apple of inspiration, they are camouflaged by the endless damp laundry tree that grows in my home.

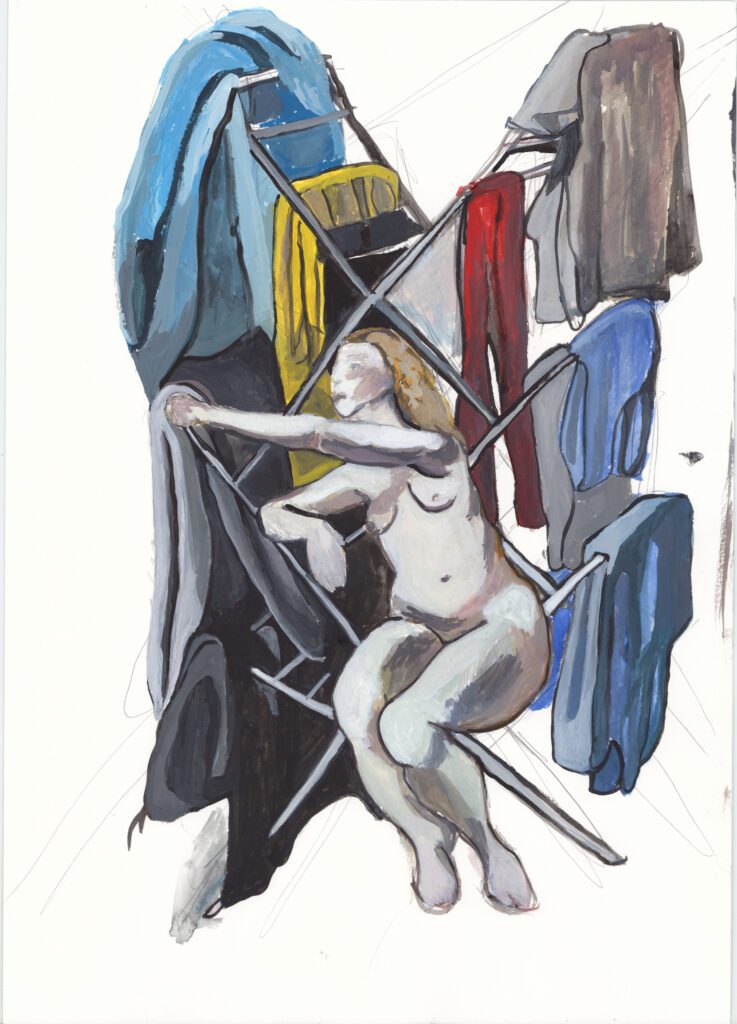

The pyjamas, the sheets, the underwear, even the red pyjama bottoms return again, as they bring with them a chorus of chaos and despair. Eden has been lost in Dressing Eve Again (2021), where I borrowed Jacob Jordaens’s Adam and Eve (1649) [8] for this naked, and tired, Eve, who can never fully clear the hanging rack before it fills again.

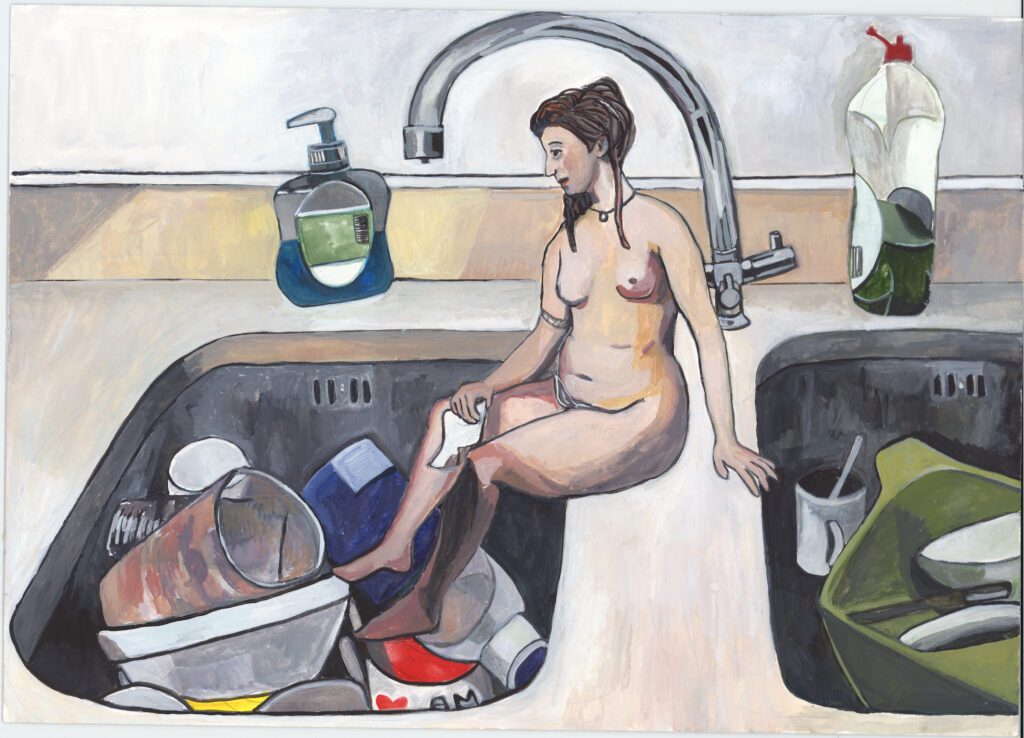

There is another heroine in Drawing Bathsheba’s Bath (2021), whom I borrowed from Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654). [9] Bathsheba is stranded in my kitchen, no longer enveloped by the dark rich background that cushioned her in Rembrandt’s painting. Instead, she is on the cold, hard ledge of my sink and with no attendant to wash her feet. She is holding a letter in her hand, the contents of which are unknown. It might be a love letter from King David, but it’s more likely to be from her employer about new student online teaching guidelines, or just another page of endless printouts for her son’s home schooling.

Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath is considered ground-breaking in the history of art. Rembrandt’s work breaks with previous tradition through its portrayal of realistic detail. My painting also has a realistic view of women’s lives and homelife. Here we do not have an idealised woman but one whose body reflects the body of a real woman. In her ordinariness, Bathsheba is depicted as plump and pale, and I wonder if, like me, she has suffered some recent weight gain during lockdown. Unlike Rembrandt’s ‘Peeping Tom’ painting, we do not lust after Bathsheba—instead, we hear the sighing of a woman overwhelmed by domestic chores, her sinking self-worth circling the drain among the detritus of last night’s dinner. And like the works by Masaccio and Rembrandt, my artwork fights against ideals, which in this generation might be compared to those Instagram perfect posts of happy homes and spotless kitchens.

Notes

[1] Michael Savage, ‘Housework falls to mothers again after Covid lockdown respite’, Guardian, 19 December 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/dec/19/housework-falls-to-mothers-again-after-covid-lockdown-respite (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[2] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/knights-the-deluge-t05532 (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[3] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/spencer-the-resurrection-cookham-n04239 (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/aug/10/stanley-spencers-the-dustman-or-the-lovers (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[5] https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-dustbin-cookham-149226 (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[6] www.sartle.com/artwork/timoclea-kills-the-captain-of-alexander-the-great-elisabetta-sirani (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[7] https://www.thehistoryofart.org/titian/fall-of-man/ (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[8] http://emuseum.toledomuseum.org/objects/54885/adam-and-eve?ctx=8e24cdb5-2360-49cf-a5a7-f3d47ac867b0&idx=250 (last accessed 20 March 2023).

[9] https://www.rembrandtpaintings.com/bathsheba-at-her-bath.jsp (last accessed 20 March 2023).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey