Beholding Blue & Seeing Red: A Downward Story in Six Movements

by: Maria Gil Ulldemolins , October 5, 2020

by: Maria Gil Ulldemolins , October 5, 2020

1. In the Beginning, There Were Two Bodies (Introduction)

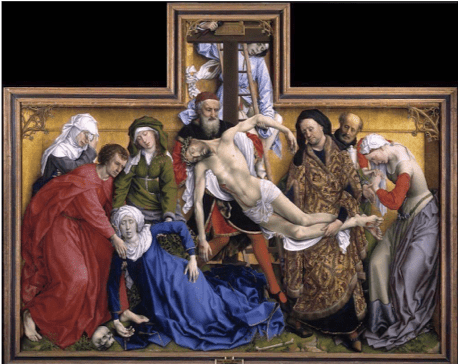

‘Behold thy mother’ (John 19.27), says Christ from the Cross. So let us start here, before death. As dying kicks into motion, Mary remains standing still (John 19.25). We can see her in our mind’s eye, sober. Then the vinegar, the sigh, the head, bowed. The motion downwards begins. Gravity pulls. We will need to behold this mother by both supporting her and staring at her, for she is now fully becoming Mary, arriving into her role in a slow-motion collapse (‘her suffering becomes the justification of her divine role’ (Neff 1998: 255). Behold the Virgin swoon.

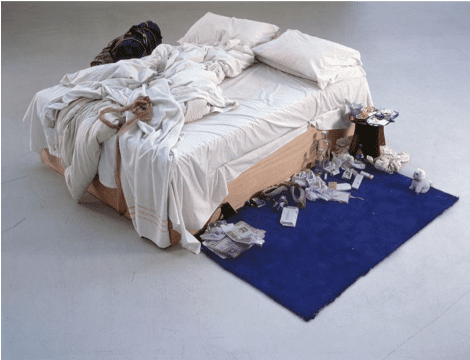

And now, behold Tracey Emin’s bed.

But a bed is not art! And a virgin cannot conceive, yet here we are.

‘A mother-woman is a rather strange “fold” (pli) which turns nature into culture’ (Kristeva 1985: 149).

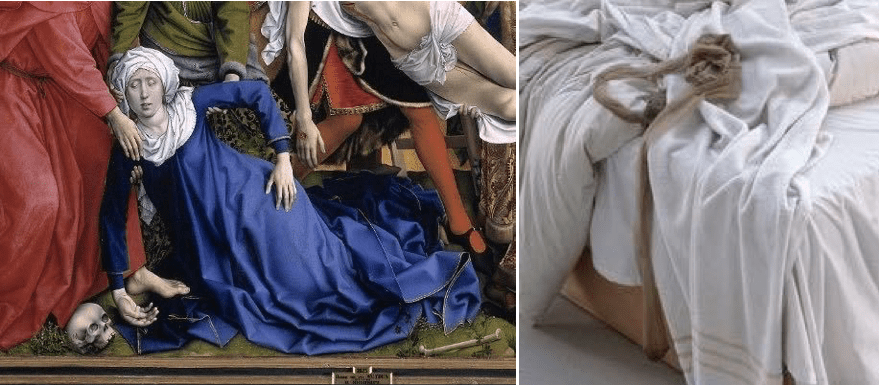

You have seen the stream of Flemish blue cloth, and the six tears on her face (you probably cannot count them from here, but there they are). Now, look at the blue rug on the Brit’s floor, starry with lint (that, you can almost see). Look back at Mary’s headgear, all that angled wrapping. Now, look at Emin’s bunch of tissues, piled high, on a corner; at her linens, storming the surface of the mattress.

Look at the Mother of God, broken, falling. Look at Emin’s scene, broken, fallen. The difference between a falling woman and a fallen woman is huge. Nonetheless, the formal similarities between these two images, Rogier Van der Weyden’s The Descent from the Cross (1435), and Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), cannot be denied and demand acknowledgement. Put the two together and, like magnets, they crash into each other with supernatural force. It may not be meant, but that does not imply that it is meaningless—it is not an accident, it cannot be. Rather, it is five centuries, a bit more, of accumulated imagery; of Catholicism lapping in and out, like the sea on the coast of European imagination, anchoring somewhere on the back Emin’s mind, prodigious in her own terms, and slowly steeping there.

2. The Pathosformel of Objects

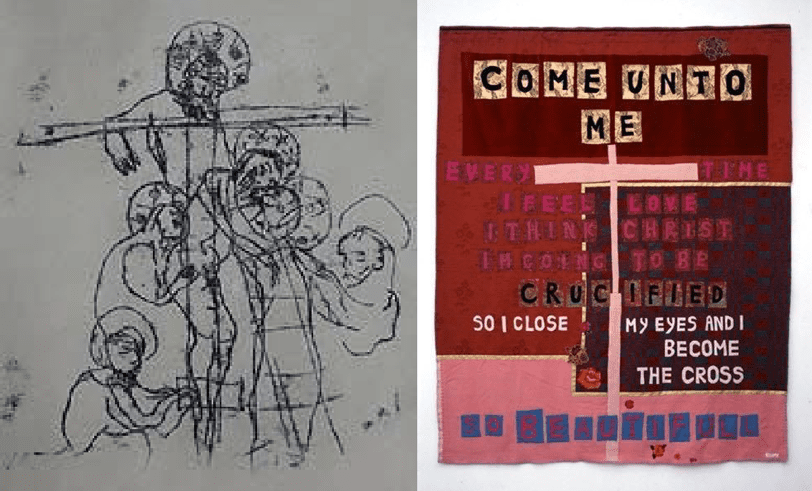

Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne plotted visually the uncanny ability of images to reappear through history, beyond the logic of historical linearity. Warburg uses images knowingly, the photographic print conveniently packaging the concept and/or the object into a format that is easy to handle. This way, even if the oil painting of a woman swooning is physically very different to an installation with real-life objects, a relationship is possible between the two of them once turned into images. One might call this relationship between Van der Weyden’s and Tracey Emin’s works the survival of Catholicism, the Nachleben (Warburg’s word of choice) of Depositions (or the comeback of bodies laid to rest). Emin appears and states: ‘I did lots of depositions’ (Brown 2006: 113). And despite Emin’s early art purge (Brown 2006: 113), when she got rid of many of her initial pieces, many of which made direct Christian references, we can still find at least one of them (below, left). The permeating power of the image adds up, soaks through. Emin cannot undo the hours observing and drawing crucifixion scenes, she has made them hers.

Obsessions have a way of eventually catching up with us, feed our motivation and inspiration, haunt us—ask Warburg. It is only logical then, that Emin’s love of Catholic imagery eventually shows, even many years later, and sometimes very literally (below, right). Sometimes, though, as I would argue that such is the case here: with My Bed, these influences permeate more subtly.

***

And this, this is nothing but an exercise in faith, you know. A belief that there is something worth saying somewhere inside, and if I just pull words out like some heretics pulled guts out of martyrs’ bodies, something holy will come out; and if not holy, whole, something pure, maybe, original, at least. But tell me, tell me if you can be original with the internet in your pocket.

***

Words like rabbit skin, something to make glue from, furry, bloody, still too animal. Push them into a twisty stick for easy distribution and finger-free handling. To mess, or not to mess, that is the question. How sticky a situation you want to make here, twist that bar up, push it all over the surface here, let the dust settle into it, the dog hair, maybe a tiny fly.

Let it dry, shh, shh, let it dry. Pull your hair up in a bun, higher, tighter, better. Pull your hair up in a bun and keep pulling, lift yourself up your feet, like a claw machine, do not drop your body, do not let go, keep pulling until you cannot see and everything is inner-eyelid coral.

See yourself from below, you can read the pattern on the soles of your boots. Stripes and zigzags like pneumatic wheels, you are part machine part mammal. Gear up, screen on your palm, buds in your ears, circadian rhythm pulsating blue light. Keep your skirts about you, you do not want to reveal what your legs look like, they confess your secret weakness in fox screams: all this flesh, mother, all this flesh and so little life for all of it. Only the fingertips, opposite severely trimmed nails, like a nun, I am guessing, only fingertips are to one’s advantage—to feel the surface of data, know if there are cracks, glass cracks, and you can then be part mineral, too, information ossifying on nail beds, between fingers, underneath the ouroboros ring you always wear.

You had always known that the trick was to turn your heart into an agate, translucent crusty bulbs only revealed when split. That’s why you have always slept with a hammer under your pillow, break in case of emergency, crack your heart-stone open and see for yourself if you are capable of beauty.

***

Emin’s bed’s origin story is part of the piece itself. Whether it is a candid recollection, or a manipulative fabrication designed to pull at the audience’s heartstrings (or their red-hot sense of righteousness), it spells out the Pathos[1] that the installation intends to offer:

In 1998 I had a complete, absolute breakdown, and I spent four days in bed; I was asleep and semi-unconscious. When I eventually did get out of bed, I had some water, went back, looked at the bedroom and couldn’t believe what I could see; this absolute mess and decay of my life, and then I saw the bed out of that context of this tiny, tiny, bedroom, and I saw it in just like a big, white space. I realised that I had to move the bed and everything into the gallery space (Emin 2015).

Independently of how truthful this is (the discussion at hand deals with religious imagery after all, a particular form of enchantment is intrinsic to the topic), emotion is conjured, and it echoes a primal helplessness and tragedy (and the victory over it) that is rather undeniably related to classical Art History themes, including, of course, Christian imagery in general, and depositions in particular.

Traditionally, Warburg’s notion of the Pathosformeln (referring to an embodied formula of emotion, a kind of physical trope that evolves and shifts through time) might have required personhood and limbs; but Emin’s body can still be sensed in its own absence, it reverberates (creates verbs anew) in her installation. Which means, that why, yes, there is also an opportunity for another of Warburg’s terms, that of ‘life in motion’, the representation of ‘the attempt to absorb pre-coined expressive values’ (Warburg 2009: 277): ‘the bed is folding, the bed is turning, the bed is moving’ (Emin 2015).

This ‘motion’ is a force capable of generating (and degenerating into) the constellation of stuff orbiting the bed, the ‘debris’ (Cherry 2002: 144) after Emin’s collapse. The artist’s body may not be there, but it is present, alive and kicking (Emin actually gets into the bed and throws the duvet about every time the work needs to be displayed, in order to recreate it and preserve its energy. What is more, the installation varies each time it is displayed, objects are rearranged, and sometimes substituted (Siddall 2015)).

And while the scenography as a whole is dripping in drama, observing its components individually reveals a layer of pathos that works at a micro level, like fractals. These props are not only intrinsically pitiful (see the abandoned plush dog toy? The shabby slippers?), they behave as such by power of metonymy. For instance, those dust-coloured tights you can find aloof on the foot of the bed, one leg draping down the side, the other one, curling on itself, are not dissimilar to Van der Weyden’s Mary (who in turn is a mirror of Christ’s dead body) (Neff 1998: 255).

Let us remind ourselves of another potential line for life in motion in the case of the bed, applicable as well when talking about most, if not all, contemporary art installations. At the risk of stating the obvious, while you might be staring at it from a computer screen (so am I, My Bed is currently, well, resting[2]), the artwork was conceived as a physical, three-dimensional thing. Life in motion is, ultimately, how the bed was intended to be seen in its conception. The ex-furniture is meant to enter into a physical dialogue with the visitor, its bodily proportion coming alive, the dirty commonality of the litter becoming close, not only in the sense of being near in space, but conceptually, close in their familiarity. This very phenomenon makes sense of the installation as an art form: while in earlier types of artistic expression beauty might be in the eye of the beholder, past the figurative, past objets-trouvés, past the conceptual, meaning is in the closeness and the meandering of the bodies of the audience. While Van der Weyden’s Virgin is obviously a realistic body in motion, the painting already uses a very similar strategy. Its figures are practically life-sized, making the viewer almost one more person within the scene, literally coming face-to-face with Mary’s suffering. Her body set in a downward motion, Mary would land nicely in Emin’s bed.

Dream, Where Warburgian Snakes Meet My Bed

Some nights ago, I dreamt that I had bought a snake in order to overcome my fear of them. It came in a kind of white, square tupperware, and I decided to open it in bed (which was not neat, not quite Eminesque, but it had several layers of sheets and blankets crumpled on it). The snake came out of the box, and it was not a beginner’s snake, it was a huge thing. It slid out of the tupperware, onto the bed. I was terrified, and feeling spectacularly stupid for bringing this thing home. It moved across my ankles (its touch, ugh) and disappeared into the bedding. It was nowhere to be seen, and I was torn between forgetting about it, hoping it would disappear elsewhere, and having to find it to protect my dog. Whilst searching, my father came out from under the bed, where he had apparently been having a siesta (and seemed very shocked that I disagreed that sleeping under a bed is a normal thing to do).

3. Silence & Salvation

I am weary with my moaning; every night I flood my bed with tears; I drench my couch with my weeping. (Ps 6.6)

‘Everyone focuses on the sexuality of my work. Why doesn’t anyone ask me about my thoughts on God’ (Vara 2002: 173), Tracey Emin wonders aloud, and I imagine, indignant. Maybe it is out of guilt: since God is dead and we killed him, we had better let sleeping dogs lie, in this bed or another. But maybe, nobody asks Emin about God because, whilst reading the Bible, it may transpire that the divine has a type, that of someone who says very little, at least beyond an underage ‘yes.’ Emin herself, as her hagiography goes, knows a thing or two about being a teenager under the pressure of a small town, and the unmovable force of an older idea of a man. Maybe then, because of how she dealt with these, publicly, becoming a professional loudmouth and emotional exhibitionist, nobody thinks Emin might have much to say about God. She is simply not the type, not his type. Good girls go to heaven, bad girls go everywhere, but nobody seems to want to go there with her.[3]

We began with Mary’s collapse at the foot of the cross, but let us cave further into time, here. Let us go back to Eve, (Lilith is out of the picture), from collapse to fall, to The Fall, that is, as provoked by her. Eve’s nature (as per divine design) is curious and whimsical.

When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it. (Genesis 3.6)

Mary is also known as the New Eve, Eve 2.0, a revised and improved idea of femininity. Blue robes may not resemble fig leaves, but Mary and Eve are cut from a similar cloth. This time around, Mary as a character is extra obedient, extra virginal:

Mary, though she also had a husband, was a still a virgin, and by obeying, she became the cause of salvation for herself and for the whole human race…the knot of Eve’s disobedience was untied by Mary’s obedience. What Eve bound through her unbelief, Mary loosed by her faith. (Gambero 1999: 54)

In other words, Eve and Mary are bound by the same principle, but it is the difference in obedience and compliance that creates a chasm of meaning. The first represents death, the second, life (Saint Jerome in Kristeva 1985: 137). At first glance, it may seem that ‘a swoon would show lack of perfection and grace, a momentary loss of faith inconceivable in the Mother of God’ (Neff 1998: 254). On closer examination, though, the blue overflow in the Flemish tableau is peak abidance. Her original fiat culminates not in the birth of Christ, but in his death: she said yes to bearing him, and she said yes to burying him. His death is the key part of the deal, and by seeing it through she encounters suffering unlike she had before, bearing salvation. Mary is designed as a theological tool so blunt that her words are recorded only four times (four times! [4]) in the story she literally engendered. Her agreement was explicit, and her life, tacit.

What this biblical detour is trying to illustrate is that Emin not only does not fit the bill: she is the absolute opposite. She took the violent, small destiny of her seaside town, Margate, and built a life full of her own self (‘I realized I was much better than anything I ever made… I was my work’ (Betterton 2002: 36)); her choices, and the sharing and clashing of both (a bit, maybe, like the waves she grew up with).

Precipitation

Mary falls under the weight of her son’s murder. This is not an unexpected weight, but still, similar to when someone hands you a watermelon, the idea of the watermelon’s weight and its actual weight are always different: there is a gap of imagination there, a gap that your hands reveal by dropping from here, where they expected the mental watermelon, to there, where the real fruit lands.

So Mary collapses, down, down, down, in slow motion. She knew, she knew she would fall, she knew she said ‘yes’ to a life of saying yes and not very much else, other than pain, so much pain, and a pain that is now so much more real and so much greater that her mind, the mind she does not speak, could have never given shape to it. The revelation of all the angles and sharp corners and the weight, oh God, the weight of this pain is too much. Too much, indeed: she is only human, dumb in her limitation as a mortal making deals with the divine, and dumb because she cannot speak. She does not speak, that is the deal, and the weight of her tongue, barely used, is felt on the lower teeth; and her mouth is so dry, as if she had never drunk at all, as if water had never existed. Her lips go white, parched, rendered bloodless by the will of a God that made her a privileged spectator to a gore show she could have never been ready for. The convention dictates that by her virtual majesty she should show no pain. But this pain is bigger than her, she cannot control it, it seeps in and suppurates out of her, she does not know what is inside and what is outside anymore. She is not sure that those ever existed, inside and outside, for right now there is no heaven, and no earth, and time stands still as she falls, and there is dust, and her mouth is, God, oh God, so dry.

She wears blue, the blue of the sky, the blue of the heaven she was promised was beyond. She has earned this blue. She thought she had earned it through a dove, but she realises this blue is blood money. No blood to be found in her, it is all out there, spilling from her son.

The deal was unconditional, she knew, she had given consent—as much consent as a teenage virgin can give to an almighty idea. She did not know, she could not know, that her blue, her immaculate blue, was made to soak up more tears that she could cry, a mess of grief and her son’s mass of pain. She said ‘yes,’ she was young, but now she would say ‘no,’ nothing is worth this. She wants to unburden herself of the heavy blue robes she was once proud of, but she can’t. It’s too late. She was too young and now she is too old and her son is too dead, and it is all bigger than her and she can’t, she can’t speak, she cannot even cry anymore, there is nothing left inside her except rocks of salt, so heavy, taking her down.

4. Blue Blood, Red Blood

Mary earned her blue, Mary earned the right to wear the sky and the heaven high above on her person, on her body, which was mortal but did not die (nor it did sin, nor feel pain in labour, nor did it menstruate[5] (Neff 1998: 254). Mary touched the celestial and brought it down to earth, through her—through her human body. She brought down the blue and the son of God, and that was what she did, the one thing that would become her legacy. She was a vessel for alchemy, for the blue of heaven to turn into the red of blood. Not her own, as stated, for she is free of sin—his, his blood: for all the blood she did not pour, he did. That was the deal. If ‘blood is the first incarnation of the universal fluid and “contains all the mysterious secrets of existence’” (Vara 2002: 192), Mary is just the silent messenger, the mystery might have been in her, but it escapes her. Her alchemical shift is a colour-step for a woman, but a giant leap for humankind. She birthed the death for our sins. That was the intent. That was what she was sold. That was the deal she agreed to one afternoon, with a dove.

***

I feel a nag in my belly. My period is doing that dramatic thing of announcing itself, dipping its toe out of me, and then proceeding to should-I-or-should-I-not. We all know you will, you cunt. Get on with it. My inside is already shredded and molten, let it erupt outwards and downwards.

No point in delaying it, no point in denying it.

My lower back joins in the conversation. I wonder, she says, if you write in an embodied manner, yeah, if you will always drag yourself into writing about periods. Because nobody wants more feminists writing about free bleeding and shit, right. It’s just a bit on the nose, or should I say, a bit on the vag.

And she is both right and annoying because why tell me all this when you are hurting because you are trying to expel a bunch of tissues. Fascist organs and muscles. As soon as what is yours becomes other, it is not welcome anymore: ‘There is a caravan of unused organic material coming this way. They are all rapists and criminals, these materials. We must wag our fingers and guns at them’. But beware not to become a stereotype in the process.

Women want protection, according to the American President. Because we are all little girls with daddy issues. Our global political landscape is one hell of a daddy issue. White ladies need to defend their hairspray and hair bleach, it will not be pried from their cold, dead, jewelled hands. The river of old blondes behind this man is always something out of a dystopian school (dis)function.

Red blood, red racist hats. Make my body great again! Screams the almost-black treacle loading up my uterus. Let us become a fertile mess of breasts and bones. So pro-life, my unused eggs. Like if I taught them nothing. Maybe they taught me nothing. Whichever way this goes. What was first, the chick or the egg? Like if I thought of myself as a chick, anyways.

***

Emin’s blue, though, Emin’s blue is not majestic. The blue descends from the heavens, into a robe, into a rug. It was never the blue of the sky, but the colour of a blur of days spent crying into a bottle and drinking into a pillow. The blue in the lowly, filthy rug is at the bottom of the work, at the feet of the bed. It is a blue closer to hell than to heaven, an abject shade: ‘[i]t looks like the scene of a crime as if someone has just died or been fucked to death’ (Cherry 2002: 149). You can hear the air above the bed gasping, and it is not with pleasure, but with agony. The sex on this bed is not the jouissance type, neither is it filtered through the potential of motherhood. It is more the type that tries to negotiate something between life and death. Will it kill you, or will it bring you back into the materiality of the body, proving that you are still, for better or worse, alive? This is sex used to ‘play with one’s own ‘thingness’ … the ecstasy of being relieved, for a moment, of one’s ‘personhood’ (Doyle 2002: 104).

The blue in Emin’s work is not there to save anyone but herself. If Mary’s swoon is a metaphor for second labour, and she is bringing into the world salvation through death (Neff 1998: 254); one can say that she is actually birthing her own true self, a role that gives her some depth and not only treats her as a blank space. And here Emin’s blue meets the Virgin’s again, ‘within this discourse of creativity, birth and sacrifice’ (Vara 2002: 190). Whilst her collapse is not philanthropic, and the sex suggested is not blissful nor procreative, it seems to lead to a new life, a new opportunity for the artist, who not only survived but saw her career take off significantly after the Turner Prize, where the bed was showcased: ‘Is modern art not a realization of maternal love’ suggests psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva—‘a veil over death, assuming death’s very place and knowing that it does?’ (1985: 145) Emin is, in a way, brought back from the dead with My Bed, a (Lady) Lazarus (‘Dying/Is an art’ (Plath 1962)) [6]. Dying as an art is messy and it is physical, not remote from a transcendent pleasure that overcomes the body (the French Petite Mort comes to mind), ‘the significance of the act lies outside the materiality of bodies’ (Vara 2002: 185). Mary ascended, and Emin, resurrected, in her own secular way, on the third (or fourth) day. Lady Lazarus indeed. All of which would make the bed a contemporary interpretation of the sepulchre. If this was not clear enough, Emin opted, in some of its earlier iterations, to display it juxtaposed to a noose and a coffin (Cherry 2002: 136).

5. Six Tears (A Personal Face to Face)

There are, as I said, six tears on Mary’s face in Van der Weyden’s painting. Her face is pretty much the size of mine, and it is almost at eye level (I am pretty short), so I counted them in person, face-to-face, Mary-to-me (incidentally, Mary-to-Maria), in the Prado (behold thy mother!). It is difficult, again, to do this digitally, it is almost impossible even in front of the quite large poster I bought on that very day, twice (‘for research, and for practice’, I reasoned).

I was in Madrid on a stop-over, back from an elderly relative’s birthday. She had turned ninety-five. She was storing each of those years in her body with her own dignity, and an enviable serenity. She did not know, though, that she was ninety-five. The linearity of age had stopped making sense a while ago (when that happened, of course, is also lost in the same blur). She knew she loved the people in the room, but whether they were her children, her grandchildren, or her parents was irrelevant at this point. She got a big, rectangular cake, homemade (an old family recipe, made not by baking, but by soaking cookies), and on top of it, struggling to stand up in the cold mush, two candles, a nine and a five (or a five and a nine, a enin and evif; as they kept on turning and being fixed from all sides by different party-goers). What do the numbers say? They asked. Ninety-five! She would answer, once the candles were properly arranged. So, how old are you? I don’t know, how could I know? She would stare back from her chair at the honorific end of the table. How could these two candles represent her ninety-five years? How could she know she was ninety-five if she inhabited a land with no time?

How then, could these six tears in Mary’s face represent her own suffering, her son’s torture and death, the joy of having saved humanity, and the weight of a divine deal? How do you quantify pain and belief? Apparently, six tears can do just that: maybe one tear for each day of the week, and one missing for the day of rest. Six seems plural enough, yet stoic. Six tears are, therefore, a dignified and heartfelt amount of tears. They are clear, and clean, all six of them.

Blood has left Mary’s face, and you can see that her eyes have rolled to the back of her head, through tiny slits left open by her eyelids. Mary is so immaculate, that she is un-stained by crying. Not her son’s blood, nor the image of her son’s blood can tarnish her (her eyes have given up, the abjection bounces against the glassy surface of the blank eyeball, it is like the gore cannot find a door to her blood-free inside).

Amongst all this purity, the six tears are a reminder that she is, after all, human, even as her body gives (as it had always done), collapses under the drama she is witnessing (and that I can only assume she has tried to picture before in her mind’s eye, since she has been warned of the inevitability of this moment: ‘This child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many … And a sword will pierce your own soul too’ (Luke 2: 34-35)). Her son, a piece of God, is all marbled flesh. Her own echoing body, though, underneath the blue of her contract, seems to disappear, de-materialise, a foretelling, maybe of her ascent. She is crying herself into a river. This is the end of what she was put up to do. She has fulfilled her duties. It’s all over for her, except, of course, that this is, theoretically, just the beginning.

A Very Partial List of Items Observed in Different Iterations of My Bed:

Candle holder (powder blue, glass), plus candle.

Lip Balm, red.

Handheld mirror, black frame.

Barbecue sauce, unopened, single-dose package.

Manicure scissors.

Diverse pill blisters.

Coins.

Cork.

Toothbrush, yellow.

Cigarette paper package? Red.

Ashtray with cigarette butts and matches.

Polaroid self-portrait, smiling.

Pregnancy test, used.

Durex Gossamer box, open, individual wrapped condom of the same type.

Safety pin.

Peanut shells.

6. Ecstasy (The End)

Retrospectively, one could assess that God’s preferential treatment is tied to pain. This leads us to the conclusion that knowing God might not be pleasurable, as much as it may be ecstatic. The relationship between bliss and agony is not new. Within Catholicism there is a long tradition of martyrs and mystics that have a very ambiguous, sensual relationship with God, associating the spiritual with the embodied, celebrating sacrifice and death. Not only is its most crucial narrative that of God becoming incarnate, and then dying in a horrendous fashion; the way to celebrate belief together is to ingest the body of Christ in communion. Being a believer is being flesh, being flesh is being sin, sin can only be expiated through belief. It is a credo of the body.

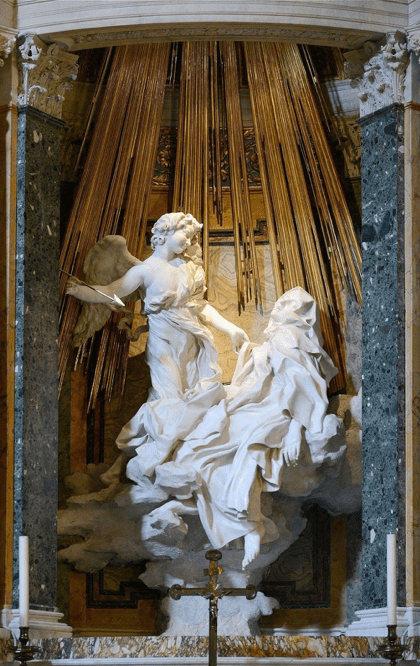

In a classic example, St Teresa’s declaration of ecstasy, an angel ‘in bodily form’ (1957: 210) has her innards ‘penetrated’:

In his hands, I saw a great golden spear and at the iron tip there appeared to be a point of fire. This he plunged into my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he pulled it out, I felt that he took them with it and left me utterly consumed by the great love of God. The pain was so severe that it made me utter several moans. The sweetness caused by this intense pain is so extreme that one cannot possibly wish it to cease, nor is one’s soul then content with anything but God (Teresa of Ávila 1957: 210).

Bernini’s interpretation of this passage is a feast of excess. There are golden rays fanning in the background, speckled green columns, and the little angel’s robe and St. Teresa’s clothes overflow into a mushroom cloud of nuclear pleasure. Look at the stony expression on the saint and that Warburgian magnetic click resonates again, bringing up Mary’s delicate face as Stabat Mater. Descend into all the white draped madness and there it is again, click, My Bed, conjured. St Teresa’s ecstasy is both pain and pleasure: ‘Sexuality implies death and vice-versa, so that it is impossible to escape the latter without shunning the former’ (Kristeva 1985: 137). It is a reminder that visually and emotionally, the collapses in Van der Weyden and Emin mix the two as well. In falling, Mary was alone of all her sex, and Emin, fallen, alone with all her sex:

A woman has two choices: either to experience herself in sex hyperabstractly … so as to make herself worthy of the divine grace and assimilation to the symbolic order, or else to experience herself as different, other, fallen … But she will not be able to achieve her complexity as a divided, heterogeneous being, a ‘fold-catastrophe’ of the ‘to-be'(Kristeva 1985: 142).

***

We ended up asleep, and every time I nod off after sex it’s extremely confusing, it’s sticky and profound and otherworldly, like no other sleep I know. We woke up in the dark, well, I woke up in the dark, you kept sleeping, and I just had this sensation that I would never get out of that daze, that I was always going to be made of canned peaches and swim in a syrupy memory of outerbodiness. I inhabited the certainty that I would never be able to stand again, wear shoes with buckles, make ginger tea, or have garlicky olives. I was just a fuzz of warmth lost between now and eternity, if one was not the other, and I was to remain vague, pearlescent and sweaty, sandwiched in sheets of time.

***

Both downward-bound, dying, different—but in process of rebirth, crying; Van der Weyden’s subject (matter/mater) is not that far from Emin’s object: ‘I always saw it as a damsel fainting, going ‘Aahhhh’’ (Wainwright 2002: 209), Emin says. Mary has traditionally been a vessel, a church (‘Mater Ecclesia’ (Warner 2016: 19)), even an enclosed garden. She might, very well, be a bed.

The Warburgian Nachleben and Pathosformeln are here, so is the life in motion: Van der Weyden’s virgin surrenders to both literal and emotional gravity right unto this bed of the nineties.

Notes

[1] For feminine collapse as a trope not of Pathos but Bathos, see Booth, Naomei (2015), ‘The Felicity of Falling: Fifty Shades of Grey and the Feminine Art of Sinking’, in Women: A Cultural Review, Vol. 26, No. 1-2, pp. 22-39.

[2] ‘My Bed has been on display recently for around six months at Tate Britain followed by around six months at Tate Liverpool. I’m afraid we have no immediate plans for this to reappear in the galleries in the next few months. The majority of the work will be held at Tate stores and with conservation after a relatively long time on display.’ As stated by a Tate Information Assistant on the 07/10/2018 via personal email exchange.

[3] The closest article I have found to exploring Tracey Emin’s relationship to God is the one quoting this question, Vara, Renée (2002), ‘Another dimension: Tracey Emin’s Interest in Mysticism’, in Mandy Merck & Chris Townsend (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., pp 172-194.; but it strays from Catholic tradition.

[4] ‘Mary’s words are recorded in four passages in the Bible. Three of the four passages are from the Gospel of Luke: the Annunciation, when she speaks with the angel (Luke 1:34 and 38); her visit to Elizabeth, when Mary sings the psalm of praise known as the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55); and the time that Jesus is lost in the Temple and Mary admonishes him (Luke 2:48). We also find Mary speaking in the Gospel of John, during the story of the Wedding at Cana. She tells Jesus that there is no more wine (John 2:3) and then tells the servers, ‘Do whatever he tells you’ (John 2:5)’ Boosted Halo 2012; see also Warner 2016: 7.

[5] Both Neff and Warner tackle this subject, Kieser, Doris (2017). ‘The Female Body in Catholic Theology: Menstruation, Reproduction, and Autonomy’ in Horizons, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 1-27. deals with it in detail.

[6] I owe my supervisor Kris Pint an early association of this poem by Plath and the collapsing motion.

REFERENCES

Betterton, Rosemary (2002), ‘Why is My Art not as Good as Me: Femininity, Feminism and ‘Life-Drawing’ in Tracey Emin’s Art’, in Mandy Merck & Chris Townsend (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., pp 22-39.

Brown, Neal (ed.) (2006), Tracey Emin, London: Tate Publishing.

Cherry, Deborah (2002), ‘On the Move: My Bed, 1998 to 1999’, in Mandy Merck & Chris Townsend (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., pp 134-154.

Doyle, Jennifer (2002), ‘The Effects of Intimacy: Tracey Emin’s Bad-Sex Aesthetics’, in Mandy Merck & Chris Townsend (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., pp 102-118.

Emin, Tracey (2015), ‘My Bed’, Tateshots, 2 April 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/emin-my-bed-l03662/tracey-emin-my-bed (last accessed 27 September 2019).

Gambero, Luigi (1999), Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought, San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Javellana, René B. (2005), ‘The “Divinization” of Mary of Nazareth in Christian Imagination: The Iconography of the Virgin Mary’, in Landas: Journal of Loyola School of Theology, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 101-118.

Kieser, Doris (2017), ‘The Female Body in Catholic Theology: Menstruation, Reproduction, and Autonomy’, in Horizons, Vol. 44, No. 1 (2017), pp. 1-27.

Kristeva, Julia (1985), ‘Stabat Mater’, in Poetics Today, Vol. 6, No. ½, ‘The Female Body in Western Culture: Semiotic Perspectives’ , pp. 133-152.

Kubutz Moyer, Ginny (2012), ‘How Many Times Does Mary Speak in the Bible’, Boosted Halo, 13 August 2012, https://bustedhalo.com/questionbox/how-many-times-does-mary-speak-in-the-bible (last accessed 27 September 2019).

Neff, Amy (1998), ‘The Pain of Compassion: Mary’s Labor at the Foot of the Cross’, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 80, No. 2, (Jun. 1998), pp. 254-273.

Plath, Sylvia (1962), ‘Lady Lazarus’, Poets.org, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/lady-lazarus (last accessed 27 September 2019).

Siddall, Liv (2015), ‘Nice Process Video from Tate on how Tracey Emin Installs her Bed’, It’s Nice That, 31 March 2015, https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/tracey-emin-my-bed (last accessed 27 September 2019).

Teresa of Ávila (1957), The Life of Saint Teresa of Ávila by Herself, London: Penguin Books.

Vara, Renée (2002), ‘Another Dimension: Tracey Emin’s Interest in Mysticism’, in Mandy Merck & Chris Townsend (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., pp 172-194.

Wainwright, Jean (2002), ‘Interview with Tracey Emin’, in Mandy Merck & Chris Townsend (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., pp 195-209.

Warburg, Aby (2009), ‘The Absorption of the Expressive Values of the Past’, in Art in Translation, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 273-283.

Warner, Marina (2016 [1976]), Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Biblical References

‘Genesis’, New International Version, https://biblehub.com/niv/genesis/2.htm (last accessed 30 September 2019).

‘Gospel of John’, King James’ Bible, https://biblehub.com/kjv/john/19.htm (last accessed 30 September 2019).

‘Gospel of Luke’. New International Version, https://biblehub.com/niv/luke/2.htm (last accessed 30 September 2019).

‘Psalms’, English Standard Version, https://biblehub.com/esv/psalms/6.htm (last accessed 30 September 2019).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey