Becoming a Blockade: A Diffractive Reading of an Academic Office as the Site of a Queer Feminist Pedagogy of Resistance

by: Ki Wight , January 27, 2020

by: Ki Wight , January 27, 2020

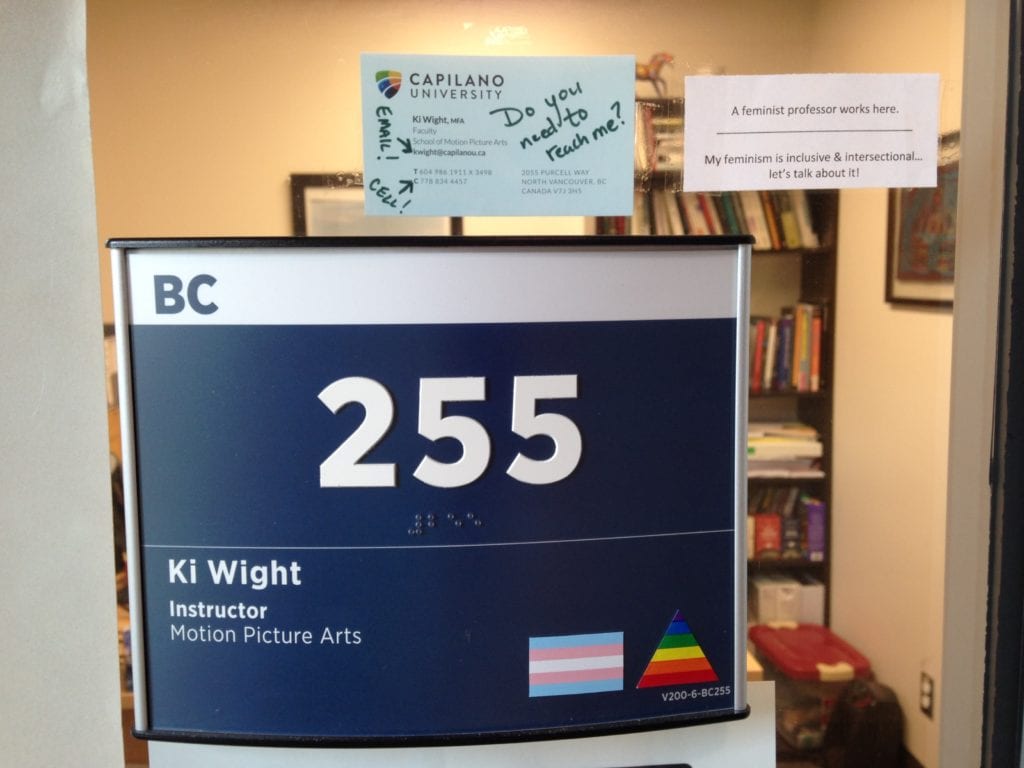

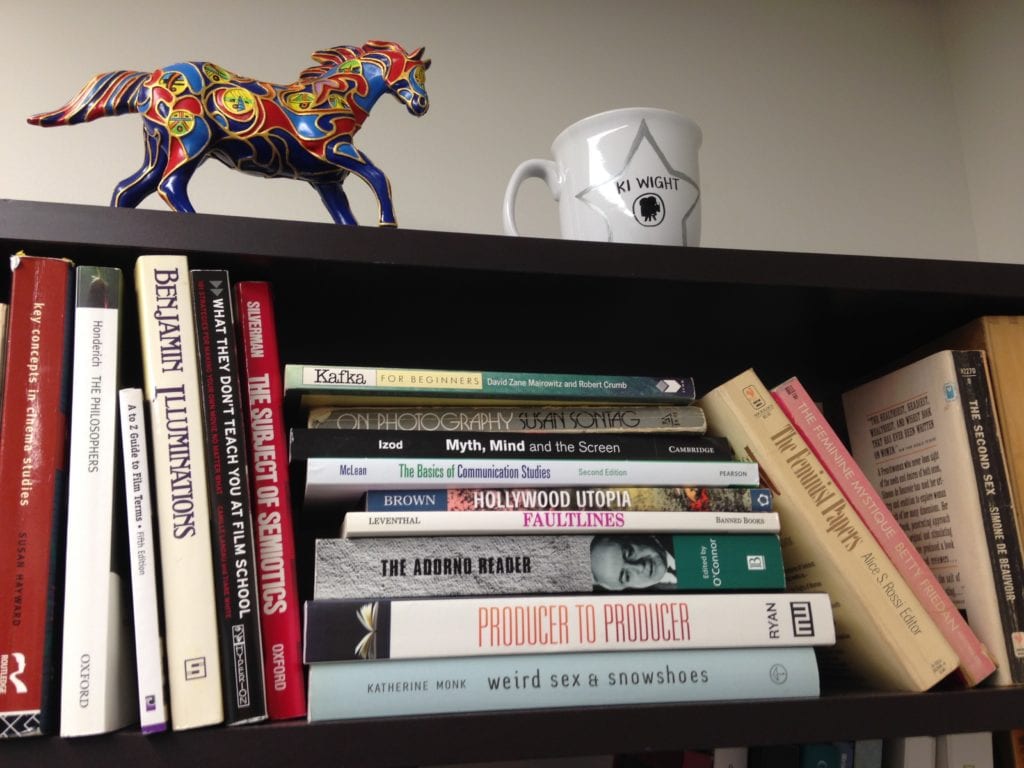

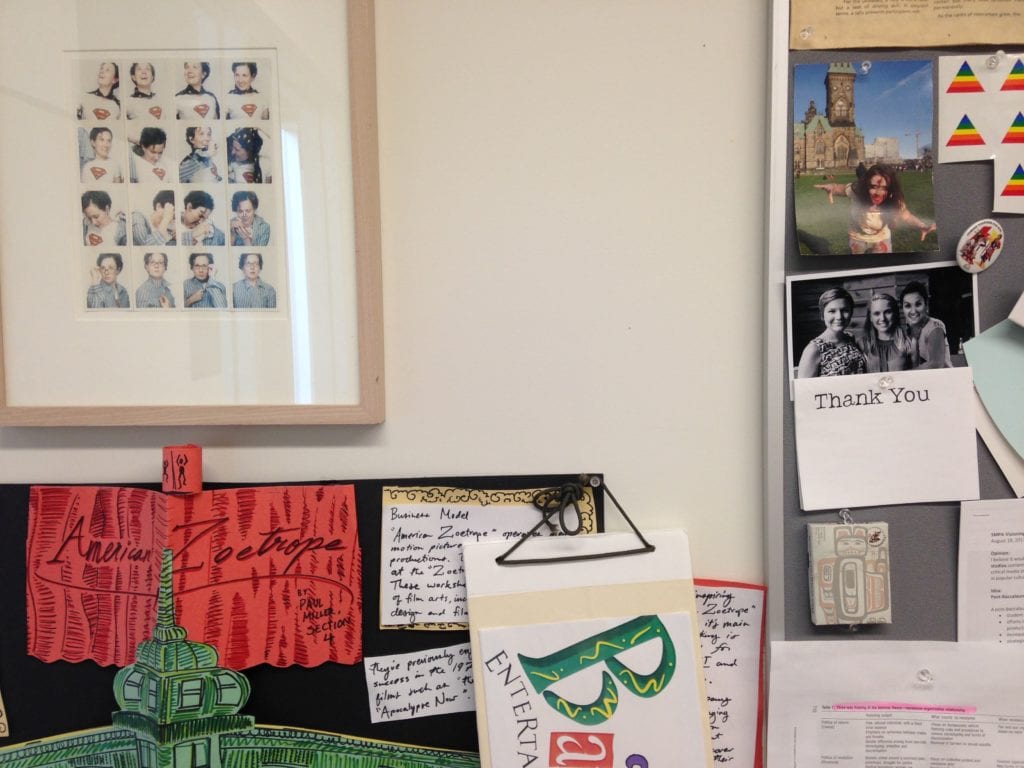

My academic office is messily furnished with scholarly artefacts, mismatched artwork, a few personal mementos, and of course tea and snacks. When looking around my office, I recall impulses to tape, pin up, post, or display certain objects or words in the crowded space. The clutter functions as an affective uttering of pride, positionality, dismay, disgust, inspiration, and other tenets that I hope find the eyes of students and colleagues when they pop in or walk by.

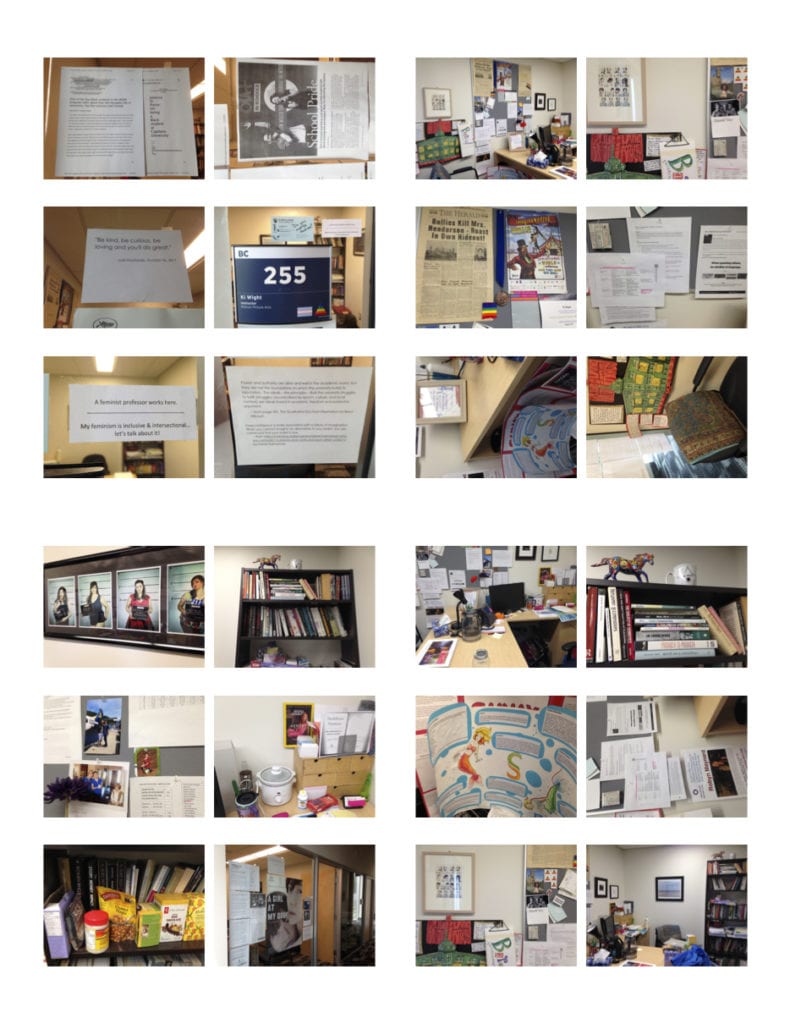

This article outlines a research experiment on the space of my office in relation to my often-resistant stance as a queer feminist media educator in a Canadian public university. I explore how my educational identity is outwardly expressed, and consider the functions or impacts of this expression on others. This is important to me because I want to ensure that my daily academic performance and embodiment aligns with core feminist principles of equity and collectivity. The research analyses twenty-four pictures that randomly capture both wider aspects and close-ups of the room; the site of the office is both the subject and object of investigation. Questions guiding this analysis are: what does my office space represent to my colleagues and students, or what does it communicate?

Does my office evidence the values of inclusivity, dialogue and respect that I cherish, or does it function to exclude? How does it orient me in relation to others in the space? Who does it work for and against? What kind of pedagogy does it signal, and does it produce or engage any ontological or epistemological standpoints? What does it perform? Does my office succeed in resisting the often conservative, neoliberal, and heteropatriarchal forces that strongly shape my world in a careerist applied education program? These questions engage core social justice educational concerns about how pedagogical choices enact or inhibit equitable orientations in academic institutions.

Moving Images: A Resistant Research Methodology

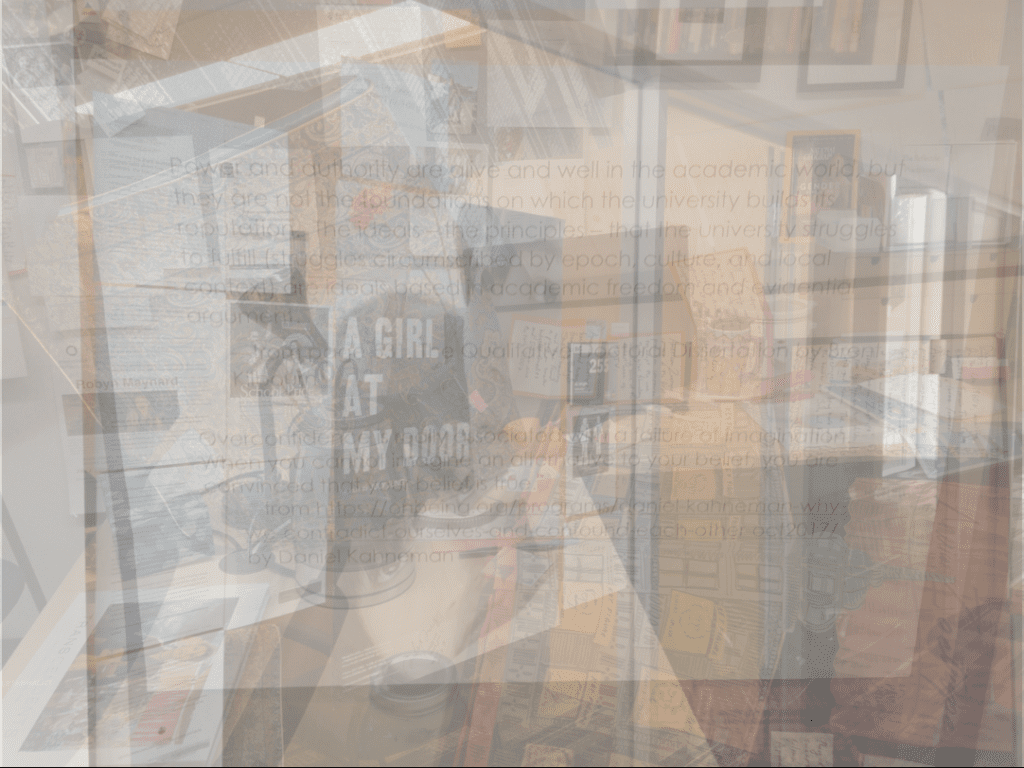

The twenty-four images that form the dataset are entrenched with literal associations that are difficult for me to step back from and reconsider. Therefore, as a way to unhinge or reposition myself for this analysis, I undertake a diffractive reading of layered image assemblages as a way to conceive and re-conceive my pedagogical performance and messaging. Drawing from the work of Donna Haraway, Karen Barad offers diffractive readings as a methodology that resists homogenising, reductive, objectifying and essentialising research actions and outcomes. For Barad, diffraction allows us to read ‘insights through one another in attending to and responding to the details and specificities of relations of difference and how they matter’. (2007: 71) What I hope to achieve in this analysis is a thinking through layered images to arrive at some fresh theoretical lines of flight (Deleuze & Guattari 1998) on resistant pedagogical performances in educational spaces. Diffraction offers a more indeterminate lens, and can be understood as a queer take on feminist methods that focus on reflexive self-study; the un-fixed and dynamic nature of diffraction is what makes this method queer. While reflexivity is a critical tool for self-awareness, a diffractive reading of an assemblage forms a unique and living inquiry that ‘enables a better and “queerer” representation of subjectivity and the mode with which this subjectivity is structured and produced in social encounters’. (Misgav 2016: 730) This queerness in diffraction, then, is what can help me see beyond my intentions to uncover new subjectivities, and shifting, variable or even contradictory insights. Barad critiques reflexivity for its static function in research by stating that it ‘does nothing more than mirror mirroring’ (2007: 88), somehow affixing or constraining a researcher’s insight. So, the diffractive reading is intended to be both generative and challenging.

As Bronwyn Davies states, ‘Whereas reflection and reflexivity might document categories of difference, diffraction is itself the process whereby a difference is made and made to matter’. (2014: 734) For Davies, linear thought is interrupted in a diffractive analysis, leaving room for new questions and possibilities to emerge in the research data. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang suggest this mattering of difference is the refusal of colonising metanarratives, stressing the importance of academic work as tangible anti-colonial action (2014: 817); in refusing settled colonial epistemologies and ontologies, there is opportunity for material research impact. Patti Lather presents difference that matters as muddied scientific epistemologies due to ‘ontologizing indeterminacy’ that brings both uncertainty and new possibilities to empirical research. (2016: 126) Diffractive analysis is, thus, resistant by nature: its constant movement and indeterminacy troubles the arrogance and certainty of solidifying empirical research ontologies. For example, instead of making specific research claims, diffraction presents questions with multiple or troubled research insights. A classic critical media discourse analysis might focus on an ‘interpretive “reading” of a sample of media texts in order to expose the dominant episteme (knowledge), assumptions, ideologies or values underwriting them’. (Atkinson 2017: 279) However, my aim is to experiment with theory and methodology that loosens, fragments and sprouts new and multiple insights rather than exposes things that I already know are there. There is also a tension in this pursuit, in that my self-motivated analysis cannot claim impartiality. Given this strain, my diffractive methodology is better considered as a learning tool for a pedagogy of resistance that is nimble, creative and unconventionally responsive and responsible. At the core of this inquiry is the fact that I am often at odds with my institution because of its prioritising of rote technocratic and heteropatriarchal educational structures; my own sensibility prioritises deep democracy in classrooms and media cultures, and maintains a visibly queer and feminist professional identity. Lather’s work has helped me see how a diffractive reading might progress my concerns in this inquiry: ‘The question is how might we move from what needs to be opposed to what can be imagined out of what is already happening, embedded in an immanence of doing’. (2016: 129) In thinking with Lather, a diffractive reading of what is already happening and already being performed in the space of my office is a good place to start. Thus, this analysis is a journey to apprehend shifting and resistant pedagogical objects, actions and gazes.

The Method: Layered Images and Theory

The twenty-four source images, which are shown below, all capture different aspects of my office space, with the goal to avoid spotlighting any one object. But, in looking through the images, certain elements do appear more than others. These images are followed by a series of six modified pictures. In conceiving of a diffractive reading, the photos have been digitally overlapped in partially transparent layers so that the representations are changed significantly, but retain some legibility. Four images are layered one on top of another with a 60-80% adjusted transparency with a goal of blending them well, but avoiding washing out into murky greys. A numbering sequence from one to twenty-four forms a grid that reduces the images to six visual assemblages.

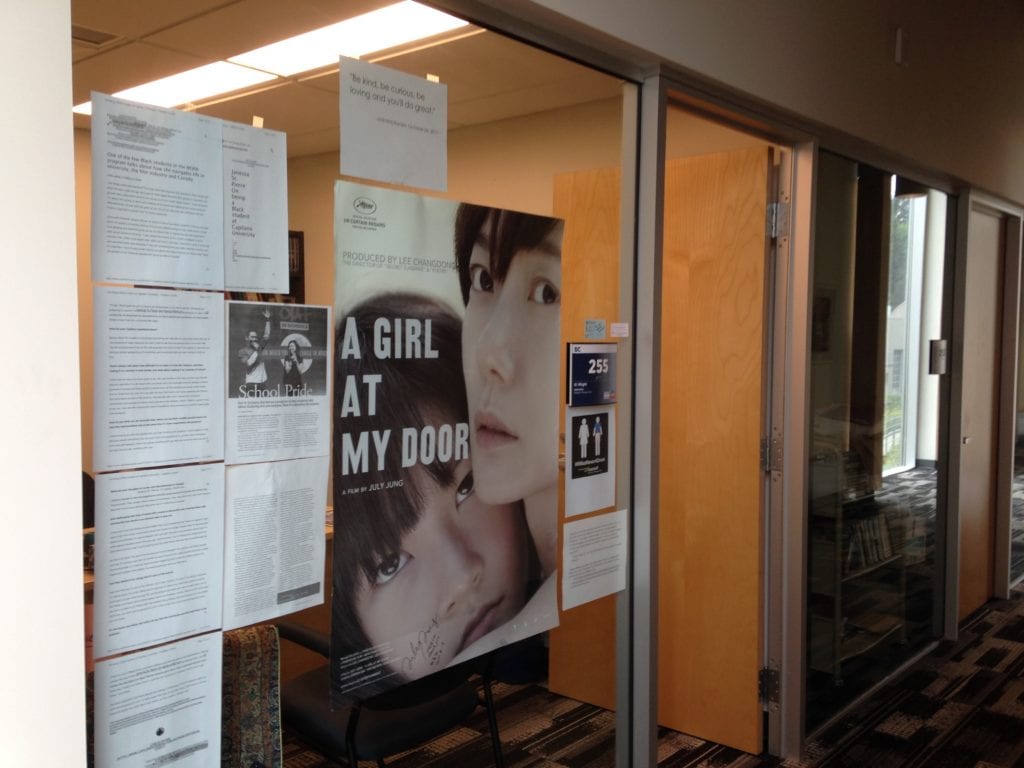

While completing the layering, I noticed that I was longing for parts of images that were disappearing in the gradations: the trans pride sticker by my office name tag; the headline for an Out in Schools magazine article; the fierce look of actor Doona Bae in a poster for a queer South Korean film by July Jung. I recognise a tension between what I thought were the most important markers and what was showing up and showing through. Sometimes, adjusting the transparency within my range helped me to recover some of these lost elements, but I tried to simply allow the layers to remain as they were so that I could force myself to see something new. After all, I would never be able to produce ‘multiplicities and excesses of meaning and subjectivities’ (Jackson & Mazzei 2013: 263) if I had a stranglehold on the visual content. Lather explores the potential outcome of a diffractive methodology: ‘Rather than meanings, this allows for patterns of configurations that open up to unexpected reading of and listenings to materials in what might termed “fractal analysis”. (2016: 127) The pictorial assemblages are layered in a fractal manner, with theory responding and interacting with fragments to produce a multiplicity of meanings and reflections. This approach enables me to put the notion of impartiality aside in favour of a pursuit of multiple, emergent pedagogical insights.

Theory and Analysis, Materials and Mattering

Seeking to trouble my thumb-tack intentions and identities, this analysis undertakes a ‘thinking with theory’. (Jackson & Mazzei 2013: 261, Mazzei 2014: 744, Smythe et al. 2017: 167) Sara Ahmed’s queer phenomenology imagines queer orientation to spaces, cultures and identities as a slippery disorientation by failure to connect to heterosexual expectations. (2006: 11) With this sense of disorientation and failure, I flip through the images quickly with a loose gaze. What emerges, first, is the great volume of colours, shapes, and words overlapping, and I wonder how big my little office appears to people walking in or around it. The colours and words flow together, potentially encircling, overwhelming, talking back. This brings to mind how Ahmed conceives of spatiality: ‘how much “feeling at home” or knowing which way we are facing, is about making of worlds’. (2006: 20) Ahmed’s world-making, combined with the notion of home, produces a spatialised queer ontology that, when applied to my office, is like an academic carnival of images, objects, and words. Carnivals are garish and noisy, and my office likely calls out to colleagues and students who are welcoming of this orientation, but deters those who don’t feel welcome or comfortable at the party. One of my original questions emerges: who does this loud space work for? Ahmed notes that ‘A queer phenomenology would involve as orientation toward queer, a way of inhabiting the world by giving “support” to those whose lives and loves make them appear oblique, strange, and out of place’. (2006: 179) So, my office space is a particular kind of open door. This certainly aligns with my instincts to loudly queer the campus as a way to support students who might have a hard time fitting into the hegemonic cultures of the academy.

Flipping through the images again, a feminist ethic of care that Monika Rogowska-Stangret characterises as having ‘unruly edges’ (2017: 11), emerges in glimpses of bold hand-drawn art, shared photographs, thank yous, “made good” food and tea packaging. These edges challenge neoliberal university pressures by ‘sharing vulnerabilities’ (2017: 13) and working collectively towards more humane and less precarious academic environments. While care is signalled, it is not necessarily comforting, and I am reminded of Megan Boler’s feminist pedagogy of discomfort that seeks to reconcile our epistemological and ontological perspectives with ‘collective accountability’. (1999: 177) Boler’s work is relational and in opposition to the Western tradition of fierce individualism. Her academic unsettling produces unstable identities as students and faculty share in questioning their assumptions and beliefs in relation to conflicting and historically-situated theories, ideas and perspectives. (1999: 183-184) Unsettled identities queer the academy through resistance to normative inquiry and academic stances. The photo assemblages can be read as harried, bursting at the edges of contained meaning, overwhelmed with quotes, and certainly discomforting for some. As Davies notes, ‘a diffractive methodology shifts research from the concept of difference as categorical difference to difference as an emergent process’ (2014: 740), drawing meaning in an ongoing manner of morphing and folding. In the assemblages of my office, there is an emergent pedagogy of discomfort that engages the sensibility of queer phenomenology, and a resistant and unruly feminist ethic of care.

Flipping back and forth again through the images, I cannot ignore the omnipresence of the pride flag, and I wonder what the impacts are of the flag in the institution. Jerry Lee Rosiek and Julia Heffernan critique how qualitative research silences queer subjects: ‘the performance of heterosexuality as an identity requires the existence and then exclusion of homosexuality’. (2014: 730) In this analysis, the pride flag is posted prominently in my office, and refuses to be silenced because of failed expectations of gender or sexuality. In this reading, the flag challenges the heteronormative binary of a singular research gaze. The office space, then, is not neutral. It signals very specific positionalities, identities and ideas, which in turn form an onto-epistemological blockade that indicates that gendered and sexualised ideas, objects, and bodies matter. (Butler: 1993) This blockade is also the matter of academic resistance, forming critical walls of care and difference. The question remains, though: how does this blockade function within and for my academic community? Does it only privilege those who seek this loudly othered space? How do I teach or work with those whose gazes are refused by my office? Who does my office work for, and who does it not work for?

Ethical Quandary: Missing Voices

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang promote the importance of scholarship as objection:

Rather than chasing aims of objectivity, we encourage researchers to take up a stance of objection, one that will interrogate power and privilege, and trace the legacies and enactments of settler colonialism in everyday life. (2014: 814)

They theorise objection for scholars who are Indigenous, people of colour, and/or queer, as a way to resist a colonising impulse to affix them as only tragic or painful subjects. So, following Tuck and Yang, my office metaphor of a blockade can be understood as an ethical stance that resists objectifying heteropatriarchal and colonial pressures. As a pedagogical strategy, I am curious about how to perform this blockade as a questioning force that engages in productive dialogue or dissent. This notion of dialogue raises an ethical concern in this analysis: where are the others in and around my office space? I have not considered the readings, images and voices of people who inhabit my work space. As such, this research experiment is only a methodological start to a conceptual and pedagogical reframing towards more collaborative and communal academic experiences and practices.

The feminist participatory visual methodologies of Marjorie DeVault, and Claudia Mitchell, Naydene De Lange, and Relebohile Moletsane (2017) focus on community-minded research practices. DeVault surveys work that emphasises ‘women as producers of visual texts, participants in image making, and/or readers of images’. (2018: 176-177) If there were a second or third phase of this research project, it would be prudent to engage others, particularly queer women, in the analysis. Mitchell, De Lange and Moletsane’s notion of ‘speaking back’ (2017: 49) is particularly resonant and aligned with resistance: speaking back is a process whereby research subjects can engage and re-engage with the data that they produce as a way to ‘contest or contradict the content or messages’ (2017: 49) of prior research data. Speaking back is productively challenging through an ethical engagement in a democratic process of ongoing and ever-changing meaning-making. Jin Hawitaworn takes participation even further through co-constructed analyses: ‘Emancipatory methodologies treat knowledge as negotiated between researchers, subjects and epistemic communities’. (2008: 3) Given the ethical concerns this analysis raises about care and otherness in institutional spaces, participatory lines of inquiry would benefit and continue to trouble and expand this research.

Conclusion: Emergent Implications

This analysis is challenging and elusive: attempting to use theory to see and question beyond the periphery of my awareness is, by nature, difficult to engage with. The slipperiness of the ontological turn and queer (dis)categorisation in diffractive methodology is difficult to capture in words. Lather’s work seems to summarise my concerns well: ‘Ontologizing indeterminacy means to think differently about the subject and agency within and beyond the reflexive turn … to trouble identity and experience and what it means to know and to tell’. (2016: 126) I wonder what kind of pedagogy is enacted through all this trouble? Lather insists that the outcomes, while fractious, are ultimately democratic and productive; relational diffractive analysis both creates community and troubles the bonds of community at the same time. (2016: 128) This a core realisation: my impulse as an educator to perform a blockade is a queerly phenomenological mechanism that gives space for the students’ onto-epistemological reckoning through a carnival of questions, ideas, and objects, that are all considerate of others and otherness in our work spaces. The blockade, then, can challenge academic timelines, interfere in and amend institutional processes, and reframe and resist normative discourses. I look forward to continuing this winding journey, keeping an open door, and picking up more voices along the way.

Postscript: What does it Mean to Keep Your Job, but Lose Your Office?

After inhabiting it for nearly a decade, I have recently and, somewhat ironically, lost my academic office. This loss is officially due to the changing interdisciplinary nature of my teaching assignments; if an instructor is not housed firmly in one department, then an academic office is difficult to land in any one place due to space shortages that are managed within strict disciplinary boundaries. While I accept this limiting approach to institutional space planning, I am left questioning whether the tenor of my old office made it the most visible and vulnerable to institutional repossession. Now, for the foreseeable future, my full-time working spaces are liminal and unsettled. Given the scope of this project, indeterminacy is fitting and has the potential to prompt the next phase of this folding and unfolding line of inquiry.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2006), Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, Durham: Duke University Press.

Atkinson, Michael (2017), ‘Media Analysis,’ in Robert Coe, Michael Waring, Larry V. Hedges & James Arthur (eds), Research Methods & Methodologies in Education, 2nd Edition, London: Sage, pp. 277-284.

Barad, Karen (2007), Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham: Duke University Press.

Boler, Megan (1999), Feeling Power: Emotion and Education, New York: Routledge.

Butler, Judith (1993), Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’, New York: Routledge.

Davies, Bronwyn, (2014), ‘Reading Anger in Early Childhood Intra-Actions: A Diffractive Analysis,’ Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 734-741.

Deleuze, Gilles, & Félix Guattari (1988), A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia, London: Athlone Press.

DeVault, Marjorie L. (2018), ‘Feminist Qualitative Research: Emerging Lines of Inquiry’, in Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (eds), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th Edition, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 176-194.

Haritaworn, Jin (2008), ‘Shifting Positionalities: Empirical Reflections on a Queer/Trans of Colour Methodology’, Sociological Research Online, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 1-12.

Jackson, Alecia Y. & Lisa A. Mazzei (2013), ‘Plugging One Text Into Another: Thinking With Theory in Qualitative Research’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 261-271.

Lather, Patti (2016), ‘Top Ten List: (Re)Thinking Ontology in (Post)Qualitative Research’, Cultural Studies « Critical Methodologies, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 125-31.

Mazzei, Lisa A. (2014), ‘Beyond An Easy Sense: A Diffractive Analysis’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 742-746.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice & John F. Bannan (1956), ‘What is Phenomenology?’,CrossCurrents, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 59-70.

Misgav, Chen (2016), ‘Some Spatial Politics of Queer-Feminist Research: Personal Reflections From the Field’, Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 63, No. 5, pp. 719-39.

Mitchell, Claudia, Naydene De Lange & Relebohile Moletsane (2017), Participatory Visual Methodologies: Social Change, Community and Policy, London: Sage.

Rogowska-Stangret, Monika (2017), ‘Sharing Vulnerabilities: Searching for “Unruly Edges” in Times of the Neoliberal Academy’, in Beatriz Revelles-Benavente & Ana M. González Ramos (eds), Teaching Gender: Feminist Pedagogy and Responsibility in Times of Political Crisis, London: Routledge, pp. 11-24.

Rosiek, Jerry Lee, & Julia Heffernan (2014), ‘Can’t Code What the Community Can’t See: A Case of the Erasure of Heteronormative Harassment’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 726-733.

Smythe, Suzanne, Cher Hill, Margaret MacDonald, Diane Dagenais, Nathalie Sinclair & Kelleen Toohey (2017), Disrupting Boundaries in Education and Research, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tuck, Eve & K. Wayne Yang (2014), ‘Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 811-818.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey