And Once Again ‘A Young Girl’

by: Nell Osborne , May 14, 2019

by: Nell Osborne , May 14, 2019

A Response to Charlotte Salomon’s Charlotte, Life or Theatre?: An Autobiographical Play [1]

*

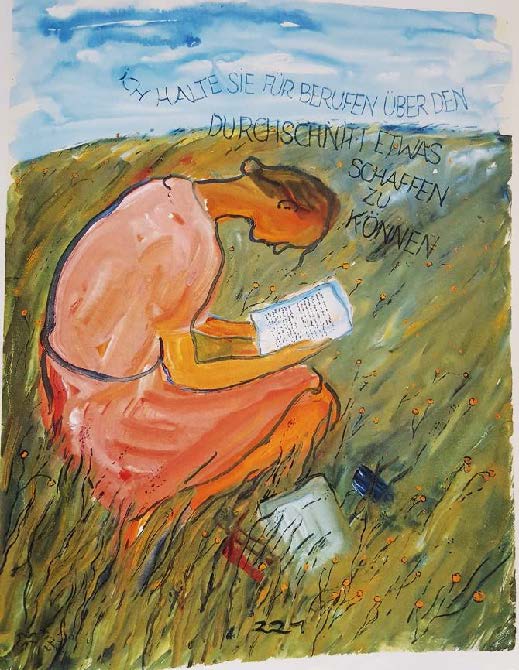

In the painting, Charlotte bends over the letter.

Her neck is thrust forwards and

steeply cocked.

The supersensitive genius Daberlohn proclaims (in the letter)

that he finds the shy young girl’s artistic potential to be:

‘above-average.’ [2]

*

Amadeus Daberlohn, prophet of song, enters to the tune of the Toreador Song from Carmen. [3]

[The cheering of crowds in the stadium].

Pageantry makes us bend at the historical

knees.

*

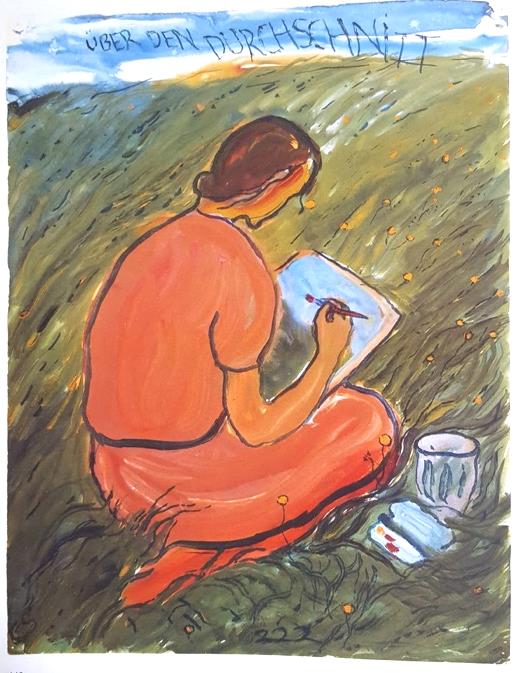

She is elated that someone finds it worth wasting his thoughts on her. [4]

She decides to make his prophecy come true and actually create something ‘above average’.

In the painting, Charlotte is painting the landscape onto her

canvas. The grammar of the horizon divides the visible into

two discrete categories. She is painting an encounter.

*

Darberlohn at a dinner party.

Albert: ‘Do you prefer red wine, or would you like white?’ [5]

Daberlohn: ‘I prefer white wine, it’s more in tune with my mood today.’

Many philosophers are highly disagreeable

people, that much seems undeniable.

Wittgenstein: ‘a serious and good philosophical

work could be written consisting entirely of jokes.’ [6]

In the painting, Charlotte sits away from the other

guests. Her back is facing us. Her mood is illegible.

Her mood is the punchline.

My philosophical tract shall be called: The jokes

that women did not make (at dinner parties).

*

At this point begins the story of Charlotte’s unhappy love— [7]

Nietzsche, the author notes, has a lot in common with the delicate 16-year-old girl.

*

In the painting, Charlotte and Daberlohn sit at either

end of a canoe. Charlotte is closest to us, chin

pressed deep down towards her collarbone,

reclining, one arm extended outwards and trailing in

the water. She is almost in profile, but she is not. She

is most definitely not.

He is struck by a remarkable resemblance between Charlotte’s pose and Michelangelo’s ‘Night.’ [8]

Daberlohn: ‘That is my new religion.’

He endeavors to implant something of himself into her… [9]

If you visit the tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours in Florence, Italy,

you will find yourself positioned before Michelangelo’s ‘Night’. The left leg pivots

upwards and across the body, touching with elbow of right arm. To look at the

body is to admire her seductive fleshly form; the muscular flank, the ribcage,

those wide-set breasts. I say her because the body is held in the moment of its

turning towards the spectator.

Michelangelo’s ‘Night’ reclines, and she is beautiful.

Only certain bodies can do certain things in certain places.

Women, for example, recline. Other women merely lie down and

wait for history to finish,

talking over itself.

Bodies recline on a chaise longue. They recline on the psychoanalyst’s couch.

But a homeless body cannot strictly be said to be reclining onto the damp

concrete of the pavement. Nor can a detained body.

Nor a body made, suddenly, illegitimate. [10]

Luxury demands an audience to recognize the value of one’s surplus leisure

time. And metamorphic rock has that in oodles. Stretch out and obstruct the

passage of time. Weep and be translucent with Artfulness.

Of course, ‘Night’ reclines (of course she is reclining).

But there is also a gathering of tension at the shoulders.

I have recreated this exact same pose in the gym, in classes called

Body Attack and Bums & Tums Blitz,

ashamedly, perspiring, grunting, gathered.

My philosophical tract shall be called: On being found unlovely in action.

*

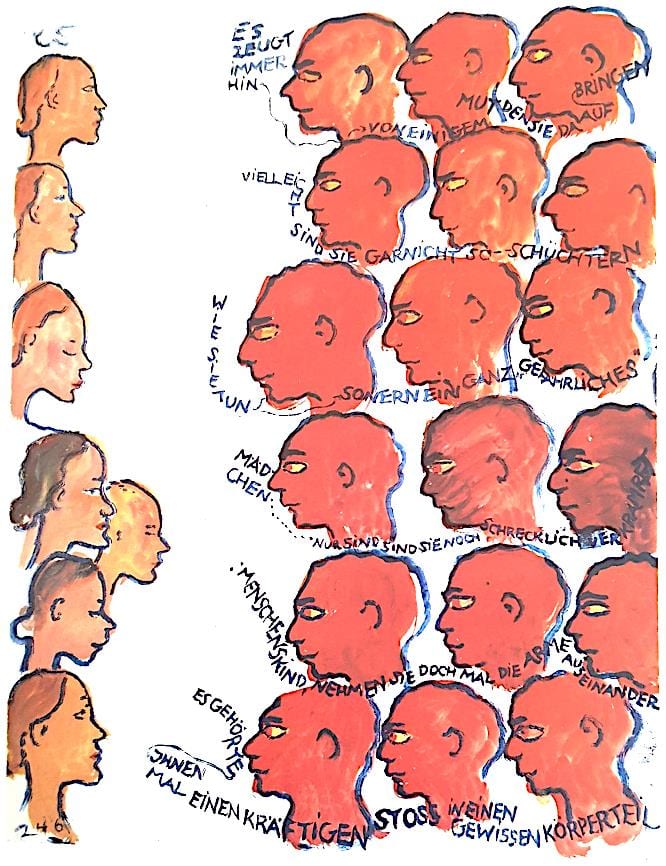

Daberlohn: ‘Perhaps you’re not nearly as shy as you make out, perhaps you’re quite a dangerous girl! The only trouble is, you’re still so terribly tense: relax child, stop hugging your chest like that, what you need is a good kick in a certain place’. [11]

He suddenly finds Charlotte significant for his theories of the future. [12]

I notice that the head of Michelangelo’s sculpture is thrust sharply

forwards, the neck turns inwards at too steep an angle for

anatomical comfort.

*

A stoop is a posture in which the head and shoulders are habitually bent forwards.

Luxury reclines. Poverty stoops. Devotion stoops. Shame

stoops. Subservience stoops. Women, workers and subjects

stoop and smile and stoop.

Women in love so frequently stoop.

*

Daberlohn: ‘What a lovely neck you have, child. Let me kiss it.

Won’t your mother be home soon?’ [13]

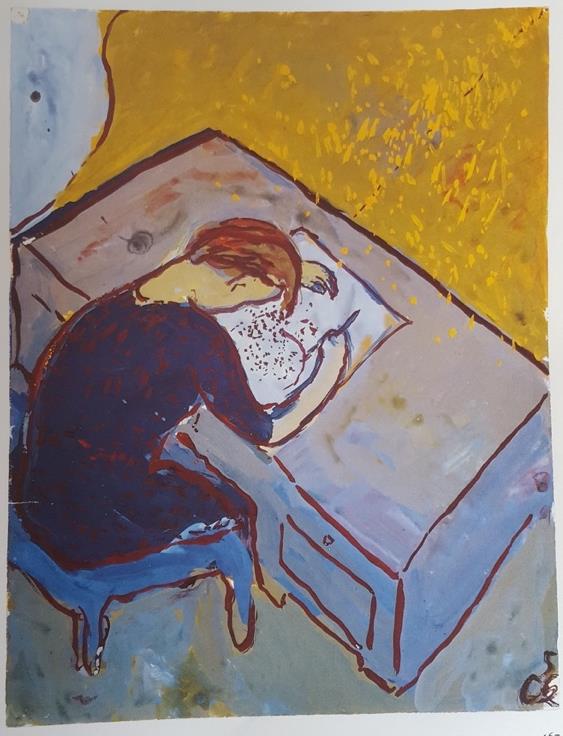

In the painting, Charlotte is a shape,

a long back and neck,

red, purple, brown,

that stoops to be kissed.

There are so few ways to talk about the body’s data.

There is perhaps only this: the world is endlessly

remade as boring material.

*

Michelangelo’s ‘Night’, but as The Fortune

Teller Fish, reading the palm of a delicate

young girl’s hand.

Moving Head = Jealousy

Moving Tail = Independence

Curling sides = Fickle

Moving Head and Tail Together, with sides

curling shyly upwards = Love.

To the tune: ‘Jesus our Lord, we bow our heads to Thee.’ [14]

*

Friend Daberlohn seems to have a very busy day ahead of him. [15]

Charlotte is most disappointed—so much so that everything within her vision becomes blurred.

*

Charlotte, seen from behind, in the blue dress, with blue

calves, the small of her blueing neck bent bluely towards the

open window and the sludge-blue-brown of the sky outside.

She is filled with grief mingled with rage. [16]

Charlotte: ‘I’ll start by throwing my money out of the window!’

Cut to outside the window: Charlotte faces us, the

reader. We are being addressed:

‘In fact, I wouldn’t mind throwing myself out too’ [17]

The room’s interior blushes darkly,

reddening with its agenda to waste.

‘But the fellow’s not worth it’.

*

The punchline might go something like this:

it’s good to feel worthless

in the street

in bed

in love, too

to be worthless

is to be outside

of —

*

Maybe ‘it’, his method, is a bit on the hard side for his object. [18]

Daberlohn: ‘Now that we have achieved this masterpiece, I’ll be off’.

He deems it wise to say goodbye as affectionately as possible.

*

The word boring comes from the mid-15th Century verb ‘to bore.’ ‘The

action of piercing’, as in ‘to bore a hole’. From 1840 the sense

changed to ‘wearying, causing ennui’. When I first learned this, I

couldn’t connect the action of piercing to the feeling of boredom

as I knew it. I was thinking about a needle, pulsating,

purpling tension, the thrill and the fear of prepping oneself for damage.

Piercing is how to get to the not-yet visible part.

But of course, in the 15th century people didn’t have electric tattoo guns.

Or electricity. I learned that with a bronze drill bit it took up to

5 hours to drill a tiny hole 1 centimetre deep in hard

stone. Piercing boredom – I got it.

Boring is pressure of the same force, in the exact same place,

over an extended period of time.

*

Is it possible, I want to know, to claim that Michelangelo’s

‘Night’ is stooping? Is it possible to stoop and to recline

at the same time?

To find a way to luxuriate in the stooping.

No tune.

*

*

Daberlohn (to himself): ‘Little girl, if you only knew what one has to go through to be able to paint’. [19]

*

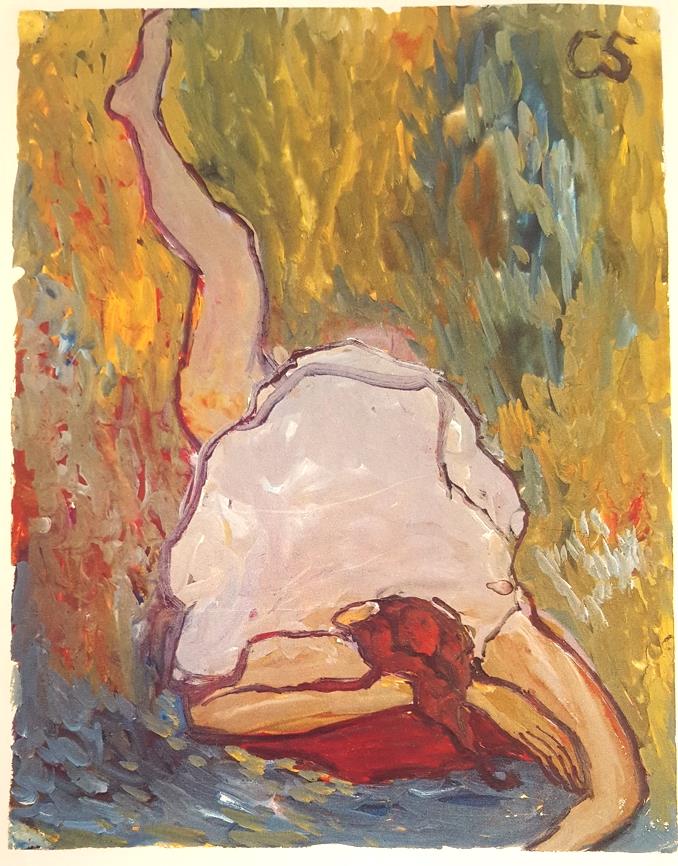

In the painting, the mother’s red hair is carefully rendered into a high coil

the effect is pretty.

In the painting, the wreckage is clearly visible.

In the painting, the dead mother is tumbling

her dress billows onion-like in its descent

from what the author specifies as the fourth floor.

Mother died immediately. [20]

Dislocated limbs form a dramatic flourish.

The body lies back, left leg thrusts improbably heavenly,

as her right arm extends outwards.

From the POV of the man on the ground I imagine the word ‘modesty’

revealing itself to have been an onlooker.

But there is no man and no ground.

There is only the space outside the body

wild with ochre, yellow, green.

The accompanying text reads:

There is nothing more to be done about tragedy.

There is something orgasmic about the painting – can that be? –

there is the red of stage curtains attending

their signal to open.

After one jumps from a window, one is always said to have fallen.

*

To the tune of: Don’t pretend to understand this

turning.

The joke is only truly perfect

when no one else but you

gets to lie with

the perversity of its

unfurling

*

Charlotte, seen from behind: her tanned back, stooped over her painting, her secret

body of labour.

Life or Theatre? [21]

She is turned outwards, towards the sea. It is very hard to talk about the body. The canvas is not painted, nor is it blank, it is transparent.

This is, of course, the punchline.

*

Notes

[1] Charlotte Salomon (1981), Charlotte: Life or Theatre? : An Autobiographical Play, New York: Viking Press.

[2] Ibid., ‘Chapter Seven: A Young Girl’, p. 441.

[3] Ibid., ‘Beginning of Main Section’, p. 213.

[4] Ibid., ‘Chapter Seven: A Young Girl’, p.441.

[5] Ibid., ‘Chapter Eleven: It looks to me as if someone Were Playing Ball with the Whole World, or Socrates Singing’, p. 498.

[6] As quoted by Wittgenstein’s friend & student, Norman Malcolm in Wittgenstein: A Memoir (1958), London: Oxford University Press, p. 29.

[7] Charlotte Salomon (1981), Life or Theatre? : An Autobiographical Play, New York: Viking Press,’Chapter Seven: A Young Girl’, p. 436.

[8] Ibid., ‘Chapter Eleven: Interesting Discoveries, for Us Too’, p. 539.

[9] Ibid., ‘Chapter Eleven: Interesting Discoveries, for Us Too’, p. 551.

[10] Charlotte died, 5 months pregnant, in Auschwitz in (probably) 1943.

[11] Charlotte Salomon (1981), Life or Theatre? : An Autobiographical Play, New York: Viking Press, ‘Chapter 10 Continued: The Resurrection’, p. 466.

[12] Ibid., p. 467.

[13] Ibid., ‘New Section, Chapter 1: And Time Marches On’, p. 624.

[14] Ibid., ‘Act Two’, p. 192.

[15] Ibid., ‘Chapter Eleven: Interesting Discoveries, for Us Too’, p. 559.

[16] Ibid., ‘Chapter Four: The Departure’, p. 562.

[17] Ibid., ‘Chapter Four: The Departure’, p. 563.

[18] Ibid., ‘Chapter Nine: And Once Again ‘A Young Girl’, pp. 523 – 524.

[19] Ibid., ‘Chapter Nine: And Once Again ‘A Young Girl’, p. 485.

[20] Ibid., ‘Scene Two of The Prelude’, p. 32.

[21] Ibid., ‘Epilogue’, p. 784.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey