A Heatseeking Erotics of Pleasurable Conversions—or, ‘Writing’

by: Rosalind Brown , June 14, 2021

by: Rosalind Brown , June 14, 2021

I seem to have two modes of writing. The first mode is functional and respectable, characterised by serious and considerate skill. I deploy known currents and quantities of energy and move them around more or less efficiently. The texture of it is smooth and appropriate. Writing emails, for instance, I build robust, urbane, immaculately punctuated prose: phrases like I understand from Vicky you are interested in, or I wonder if we could move our meeting to. Writing fanfiction, I might have someone speak wearily or wryly, or gaze steadily or curse inwardly. In moments of crisis someone might go cold, or lower their eyes in confusion.

I think of this first mode as a straightforward use of cliché, without that word’s automatic connotations of laziness. These words and phrases are skilful shorthands for particular, well-grooved narrative-emotional beats—they light up easily, but weakly, the correct sites of meaning. This mode is orderly, manipulative, vivid, and pleasurable, both for writer and reader. I add and remove commas, I comb through the thesaurus, until everything feels correct and even—not without quality or density or interest, but proper. A good comparison is the string quartets of Franz Joseph Haydn. No tension ever climbs too high, all the queries are lightly but thoroughly satisfied. The build-up and release are mild, like straightening a twisted bra strap: now there is no discomfort, now all areas are equally relaxed and reassuringly supported.

This progression, from systemic discomfort to mastery through conversion, and finally to systemic relief, seems unavoidably Freudian—the metaphors are those of Beyond the Pleasure Principle—but is also a more or less accurate description of writing. Both my first worldly writing mode and the other, darker mode (more of which later) involve a currency of energy, tension, and release, a transmutation of flickering energies in the mind into an arrangement of words on the page. And when I say writing, I do not mean the general state of being a writer, walking around circulating thematics in my head or noticing things about strangers on the street. Nor do I mean planning or structuring, working out my currents of plot, how the story will draw in and bunch up its own energy, withholding, surging, and finally yielding. By writing I mean the actual kneading, probing, palpating I do at my desk, thinking of words and rejecting some and writing down others—squeezing out the sentences. I am embarrassed not so much by how disgusting this sounds, but by how pleasurable it sounds—how pleasurable it is. Perhaps this is a way to respond, belatedly, to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s call for a discourse of female anal eroticism. (Sedgwick 1987: 110) Perhaps I might consider that the new growth of springtime, oaks and hawthorns squeezing out their ruffles of leaves, might for the trees themselves be masochistically pleasurable, or even straightforwardly painful; and I might wonder what that painful necessity illuminates about artistic endeavour.

But here I want to think about sexual fantasy, and how it too has two modes. The first mode has the same evenness and almost stateliness as my first writing mode: taking the mind on a gentle leash down certain pre-established pathways, patiently constructing a well-layered scene, with regular injections of familiar gestures and phrases, until the whole thing collapses evenly and competently into orgasm, then sleep.

And actually, perhaps fantasy is too great a compliment for that first mode. Because the second mode is, oh god, it’s almost feral: bringing unforeseen, indeed unforeseeable, inspirations where somehow a space is left, and a new twist of scenario, a wriggle of new material, appears fully-formed and panting. It is extreme, filthy, breathtaking. A kind of destabilising euphoria, a light-headedness which soars and endangers—and the orgasm when it comes pours through like a mass of water through a sluice-gate, like someone has pulled out the plug: it drains. Then, not so much sleep as a grey, dimly-lit, slightly feverish inertia. Later I might let out a low whistle of admiration for my own mind. I might also think of Henry Purcell’s famous choral anthem ‘Hear My Prayer’, in which a slow build-up of unbearable harmonic dissonance finally crashes out into an open fifth, the sternest of chords, the inorganic state of harmony, the perfect monochrome of the grave. I want all poems, all plays, all fictions, to end on the iron-hard wildness of the open fifth.

This somewhat catastrophic cadence, then, is my second mode of writing: a kind of deliberate vulnerability to unexpected plummeting. It is a feeling of remoteness, the feeling of being drenched in my mind’s own strangeness. When I have levered open my perceptual system, when I let the energy flood in a little longer and penetrate a little further before I attempt to write it down, then the words that come are indeed remote, alien, they arrive as if from over the crest of a hill. Suddenly the word that does everything, that precipitates everything, might be scrape, or rosebud, or triumvirate, or eavesdrop, or puddle. It is ultra-private, like a jazz solo is an ultra-private negotiation with quantities of tension and release—but unlike jazz, thank goodness, it is not also instantly public. On good days, and with a canny distribution of caffeine, my writing mind seems to fizzle, or take on a luminous blackness in which almost any word might have a nauseating, disorientating weight. The high is staggering, the release is exhausting.

*****

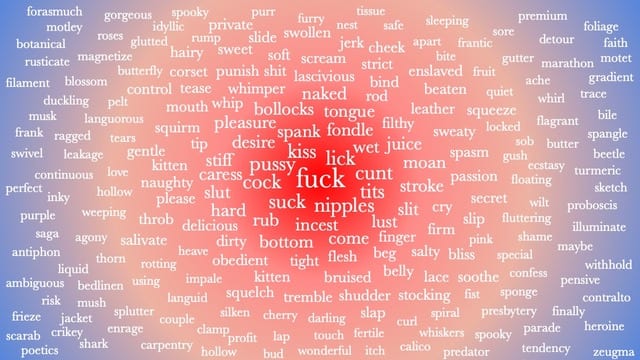

A few years ago, I started to arrange sexual words into columns, according to how denotative or connotative they seemed, how hotly they seemed to carry their meanings, how vividly they split open into the imagination. When I had the idea to write this piece, I dug out that diagram, and rearranged and expanded it. Now I present it as a radiating heat bubble, a clitoral concentricity:

Behold this sweltering wonder of sex, the immediacy of the hot words and the faint flicker of the cooler ones. It is not comprehensive. Some words on different days request transfers in and out. And certain patterns strike me—I note, for instance, the appalling misogyny of the inner clusters; also a particular concentration in the middle of words beginning with f, c, k, and s; and I chew over with interest the different positions of pleasure and please.

But most of all I perceive how navigating this topography of sex language might figure my two modes of writing—how sexual writing only does especially conspicuously what all writing does in general. To start at the outside of the diagram and move inwards is the route of a heat-seeking quest for our sociable, instantaneous language, for its excellent pornographic capabilities—and a slow or fast intensification towards, predictably, penetration of some kind or other: towards a fuck. The pace of this quest must be carefully managed, or else I might risk short-circuiting: I don’t want to get there too quickly. Even the Marquis de Sade, that regular and literal currency converter of imaginative energies, manages his libertines by having them manage their own daily schedules over their one hundred and twenty days of Sodom. I might also, as Sade is doing very much on purpose with his lists of simple, complex, criminal and murderous passions, risk being just banal.

Conversely, to start near the centre and move outwards, or even to avoid the centre altogether and roam around in the cooler regions, might be a flight towards euphemism out of discretion or cowardice, or a conscientious retreat from that central lurk of rape and abuse. Or—and—it might be an experiment in keeping an unsteady warmth at my back as I move further and further from the nerve-centre. And really it’s the remoter, temperate zones I am seeking—which requires a kind of deliberate slackening of the mind, where words can arrive and be right because of their textures, their thicknesses, their sudden weirdness and unaccountability. These might be words that can be made sexual only by an effortful metaphoric conversion—where a strenuously tempered, carefully accumulated mass of tension can be ecstatically catalysed, or even imploded, through the most bizarre and alien lexical choices. I can plot my own, highly idiomatic route through this word-cluster, and it may not even lead to orgasm: its route is uncharted, at a higher altitude, lurching, and possibly unrepeatable. The thick rich turmeric of his pleasure. He touched him with fingers that were both pensive and faithful. They built their fuck like fine carpentry.

*****

In James Joyce’s story ‘An Encounter’, two boys meet a predatory stranger who speaks in strange sexual monologues. These monologues seem to be directed not at the children in front of him, but inwardly to himself: ‘magnetized by some words of his own speech, his mind was slowly circling round and round in the same orbit’. (Joyce 1926 [1914]: 26) This form of verbal self-hypnosis, whether sexual or not, seems a possible analogue for the way any number of writers might have worked: Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, Shakespeare in his sonnets, D.H. Lawrence, or James Baldwin. And it makes me wonder whether here is a suggestion for creative writing technique—or perhaps even a creative writing ethics, where, instead of paying attention to the effect I might have on a hypothetical reader, how to manipulate her into feeling or thinking this or that, I instead tune very finely into the only thing I can know: the effect I am having on myself. This, I think, is what it means to write in good faith —to assiduously attend to myself—to try harder to make this text work for myself than anyone else would think reasonable. It’s about trying, probing, groping, for a successful conversion of one energy into another. And it gives me new respect—not so much for writing as for that other form of attending to oneself, that extraordinarily subtle and precise operation to which we give the somewhat grim name of masturbation. All of which leads back to what I hope is a move of real honesty—an authentically ethical gesture—where I admit freely that if I were having no effect on myself, I would not write.

Notes:

An earlier version of this piece was presented at ‘I’ll Show You Mine: A Sex Writing Symposium’ (National Centre for Writing, Norwich, UK, 6 June 2019).

REFERENCES

Freud, Sigmund (1955 [1920]), ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’, in Freud, Sigmund, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Words of Sigmund Freud, translated by James Strachey, London: The Hogarth Press, pp. 7-64

Joyce, James (1926 [1914]), Dubliners, London: Penguin Books.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1987), ‘A Poem Is Being Written’, Representations, No. 17, pp. 110-43.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey